“Pandemics unmask who we really are — our morals, our values, our ethics, our humanity. They test us in ways nothing else can.” — Sanjay Gupta, M.D., World War C, 2021

In a tutorial for doctor of ministry students at Asbury Theological Seminary, several of us were struggling with the new statistical component that had been introduced to D.Min. projects. Asbury brought in a sociologist-statistician to explain what we would need to do to meet these requirements in order to complete our projects and degrees. The sociologist, perhaps to lessen our stress, had prepared fudge brownies to use as a teaching prop.

After counting the number of students, she had appropriately sliced up the tray of brownies. My colleagues surged forward for free brownies.

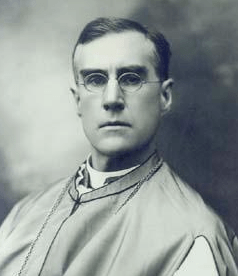

Harold Ivan Smith

Soon she seemed confused. Again, she counted the number of students and the number of brownies left. “Something appears to be wrong,” she said. Her puzzlement percolated until I fessed up, “I am highly allergic to chocolate, so I did not take a brownie.” “Well then, that explains it.”

Thirty years later, I recalled her words as I read the announcement that Asbury Theological Seminary has chosen to join Al Mohler’s Sixth Circuit Legal Roadshow to sue the Biden administration over the imposed COVID mandates for companies with more than 100 employees. Surely, had the Trump administration proposed such a mandate, both seminaries would have held their noses and have accepted it.

After reading the announcement of this lawsuit in a BNG article, I thought something had been left out of the announcement.

I understand why Al Mohler and Southern Seminary are doing this. I do not understand why my alma mater, Asbury Seminary, is joining them. Mohler — an outspoken supporter of Donald Trump — is drawn to media attention and controversy like hummingbirds to my birdfeeder. But Asbury? Really? I needed something to explain this decision because it does not square with the Wesleyan tradition.

Something appears to be wrong, indeed. The pieces do not add up.

What kind of world are we living in — amid this pandemic (there will be more pandemics in this century) — when a theological seminary, particularly a Wesleyan seminary, waltzes into federal court to sue about anything? Perhaps their justification for avoiding Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians 6 is to say they are not suing Christians, they are suing Democrats.

“Something appears to be wrong, indeed. The pieces do not add up.”

Asbury’s influence on me

After earning the doctor of ministry degree from Asbury, I entered the emerging field of thanatology (dying, death and grieving). My doctoral paper was the first doctoral-level work to explore grief following the death of friends, particularly relevant during the AIDS epidemic. I now teach the course “Introduction to Thanatology” for those entering this field.

Moreover, my Asbury D.Min. paper evolved into to an academic textbook and two general reading books. The rigor of Asbury prepared me well for lecturing in Europe, Vietnam and Australia and to have students — by Zoom — in Saudi Arabia, Jamaica and Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Over three decades as a thanatologist, I have explored not only grief following the deaths of family and friends, but also grief following non-finite and disenfranchised losses: divorce, infertility, job trajectory, bankruptcy, loss of academic promotion or tenure, and chronic non-terminal illness.

Statue of John Wesley on the campus of Asbury Seminary.

Recently I have been drawn to the radical infusion and intrusion of “theopoliticians” or “politico-theologians” into seminaries, churches, denomination boards, agencies and state associations — which has left a trail of wounded, grieving individuals. The object of grief does not have to have been embalmed or cremated to be authentic. Too many have grieved career-ending judgments by theological “mandate.”

The carnage in instituting theological “orthodoxy” has resulted in great pools of deep grief among Southern Baptists and former Southern Baptists and individuals describing themselves as “recovering” Southern Baptists. And the grief has impacted spouses, children and grandchildren and friends and colleagues.

Grief for a denomination and its agencies and institutions is a “disenfranchised” grief. One colleague who experienced the purge first-hand told me she thinks theological shenanigans led to several long-term Southern Seminary professors dying with broken hearts. And what would that “holy host” think of a lawsuit against the government in a time of unpredictable COVID-19?

I understand this dynamic in Southern Baptist life. I do not understand why Asbury is going along for the publicity ride.

How can you train future ministers who are dead?

The bombastic language of the lawsuit filed by Southern Seminary and Asbury Seminary claims they need to resist the federal mandate for large employers to require vaccination in order to “serve their students.”

The reality in this pandemic is that neither seminary can “serve their students” if they are dead. Or if they are struggling with the effects of long-COVID. Or if the students are infected by unvaccinated staff and faculty.

“The reality in this pandemic is that neither seminary can ‘serve their students’ if they are dead.”

Imagine the report: “Yeah, Billy Ed went up there to Kentucky to get himself a theological education and came home in a casket.”

Also, both schools boast about their commitment to world evangelism — but you need live bodies to evangelize. Millions of unevangelized people have died from COVID-19.

Mohler is quoted as saying the seminaries “had no choice but to push back against this intrusion of the government into matters of conscience and religious conviction.” Really?

What “religious conviction” is either seminary president talking about?

Lessons from the Spanish Flu

Timothy Tennent

I doubt Mohler or Asbury President Timothy Tennent — or any of their trustees — has researched the Spanish Flu pandemic that killed 620,000 Americans and 50 million worldwide in 1918-1919. I have written, lectured and even taught a college course on that epidemic. Here’s the reality: More American soldiers died of the Spanish Flu than on the battlefield.

Further, no Methodist in 1918-1919 would have thought about suing when government entities ordered churches closed. Pastors were too busy burying the dead in mass graves. Actually, some Methodists and Baptists dusted off the old concept of the “brush arbor” favored by early revivalists and held services outdoors. No Methodist would have said that wearing a mask on a streetcar would violate their “conscience” or “religious liberty.” And in fact, someone had to bury the Baptist who tried to board a streetcar sans mask and was shot dead by a police officer! That ended the mask revolt.

In 1919, employees of a Baptist or Methodist institution would not have hesitated to roll up their sleeves if there had been the slightest hope of a vaccine. And had a vaccine been developed, Methodists would have thrown a shouting prayer meeting to thank the Good Lord for it.

Pastors and that day’s theological educators — given the viciousness of the Spanish Flu: sick at breakfast, dead by dinnertime, buried soon after sunrise the next day — concluded they had to do everything possible to stop this pandemic that was killing their donors, students, neighbors and the recipients of their evangelism.

A hero story

In every pandemic there are heroes and complicators. While spending two years researching the Spanish Flu epidemic, I discovered a hero who was neither Baptist nor Methodist. This hero prayed, “Lord, what can I do to help?” not “Who can I sue?”

Archbishop Regis Canevin

Thus, on Oct. 25, 1918, Regis Canevin, archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Pittsburgh and shepherd of 580,000 Catholic communicants, ordered Pittsburgh’s Catholic churches — which were closed by government mandate — to set up centers in parish halls to provide nourishment and supplies to anyone. Anyone! He deputized volunteers to take food, medicine and clothing to the homebound. Even though going into a home where someone had the Spanish Flu was highly dangerous to the volunteer and the volunteer’s family.

Then Archbishop Canevin went bold. He informed William H. Davis, head of Pittsburgh’s public health department: “I feel it is my duty to place at the disposal of your bureau all resources of the Catholic Church in Pittsburgh.”

Try to imagine either Mohler or Tennent offering “all resources” of their wealthy seminaries to help the government fight COVID-19.

Then the archbishop ordered Catholic Charities to set up relief offices throughout the city “where those afflicted with the disease and suffering from the disease, irrespective of creed or color, may procure the needed aid.”

“Try to imagine either Mohler or Tennent offering ‘all resources’ of their wealthy seminaries to help the government fight COVID-19.”

And since the Catholic schools had been closed – again, by government mandate — Archbishop Canevin declared that all the teaching nuns and those in convents would now serve as “visiting nurses.” And woe to any nun who dared say, “Archbishop, I am a teacher not a nurse.” That was not something the archbishop would have tolerated for a moment. Never in the pandemic did it cross the archbishop’s mind that he ought to be suing some government agency for interfering with training future priests and nuns in his seminary.

Archbishop Canevan was too busy “doing good” and, in John Wesley’s words, “avoiding doing harm,” to consult with lawyers about suing anyone.

Canevin did not head to any court to protest that the churches or schools in his diocese had been ordered closed. He certainly didn’t huff and puff about “governmental interference.” Or even “conscience.” Why? Because his Catholic priests were driving horse-drawn wagons along Pittsburgh streets and calling out to residents to bring out their dead to load on the wagons. Meanwhile, Catholic seminarians were digging graves. (Canevin concluded that some of his seminarians needed some productive exercise.)

Where are today’s religious leaders as visionaries?

So, where are the visionary “shepherds of the sheep,” theologians, theological administrators, seminary trustees and prophetic compassionate voices in 2021?

The largest issue, according to Mohler, is “religious liberty. And on that we take our stand.” Canevin would have retorted: “What ‘religious liberty?’”

I am convinced, as a thanatologist, that vaccines work.

I am convinced, as a Christian believer, that God directly graced brilliant scientists to make breakthrough discoveries to create vaccines in rapid time.

“I am convinced, as a Christian believer, that most of the 777,000 and rising toll of the dead did not have to die.”

I am convinced, as a Christian believer, that most of the 777,000 and rising toll of the dead did not have to die.

I am convinced that they would not have died if opportunist shallow-thinking politicians and preachers had not turned COVID-19 into a litmus test via sound bites and if charlatans had not gone rogue spreading disinformation and dishing out absurd remedies.

I am convinced that too many “evangelicans” or “Republicals” (depending on the individual’s first priority) cherry-picked Scripture to bypass the implications of Cain’s “defense” in Genesis: “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

Instead of showing courageous leadership, evangelical Christians during COVID-19, driven by fear and anxiety, have chosen to listen to some of the most scientifically and theologically “light” minds imaginable.

Evangelical Christians have criticized and derided Anthony Fauci, Francis Collins, Robert Redfield and Rochelle Walensky rather than praying for them or thanking God for these scientists — as I do — who serve in an “Esther” moment, “for such a time as this.”

Whatever happened to that commandment, “Thou shall not bear false witness”? Is it not still equally one of the ten?

I am convinced that knucklehead evangelicans have spent more time scouring the web claiming they were “doing research” rather than asking, “What does God have to say about our response to this?” Or how might John Wesley’s words “serving the present age” apply in a pandemic era?

Too many evangelicans snarled, “The hell with vaccination! And hot hell with masks!” Too many have concluded and all but verbalized, under cosmetic declarations of conscience and religious conviction, “I have a God-given right to infect you.”

Follow the money

I understand why Mohler and Southern Seminary have fallen into this evangelical pattern of denying science and claiming an individualistic view of religious liberty. But I cannot understand why Asbury Seminary — rooted in the Wesleyan tradition — has joined the fight with the Southern Baptists.

I have long heard the adage, “Follow the money.” And Asbury President Tennent wrote me explaining that, in fact, the decision to join the lawsuit was about “the money” driven by the fear of exorbitant fines for violating the mandate.

No doubt it also is about the money needed from more politically conservative donors, as Asbury currently seeks to raise $100 million “to preserve” the seminary for its next 100 years. That now appears to include appealing to the political views of donors more than preserving the lives of students and faculty.

I served 10 years as a trustee of a graduate theology school. I understand that “deals” get made in committee meetings, over coffee at Starbucks or during breaks in sessions or between sessions. Or, increasingly, by cell phone or text.

I realize contemporary seminaries have an unquenchable thirst for money. Henry Clay Morrison, Asbury’s founder, never could have imagined a $100 million fundraising campaign. (In his day, a $100 donation would have provoked a spirited “Doxology.”)

“Seminaries, Christian colleges, megachurches all have to dance to the tune called by donors —especially big-ego donors.”

Admittedly, the realities of theological education these days keep advancement folks busy. A president, expected to be a “rainmaker,” has to work the phones and electronic media, persuading, cajoling and “making merry” with donors lest they wander from the donor fold given the barrage of requests for their money. No surprise then that when a big donor calls and says to a president, “Either you do x, y, or z” (or all three) you’ve seen the last check from me.” Few seminary presidents respond, “Well, now Brother Big Donor, can we have a word of prayer about this?”

Seminaries, Christian colleges, megachurches all have to dance to the tune called by donors —especially big-ego donors.

You do not keep a seminary functioning by preaching, teaching or publishing books written by faculty but by keeping the money coming in. And by keeping big donors happy.

I’m writing because I bury the dead

Why am I angry about all of this? Because I bury the dead. I write about the dead and the dying. I teach continuing education courses for grief therapists and nurses in hospitals, hospices and in funeral service.

I’m angry because during COVID-19, I have spent hours listening to grievers describe their anguish at being unable to have been “with” their loved ones as they died. I have buried people who have died from COVID-19. I have buried people who relapsed from substance recovery during the isolation of COVID-19.

And I have buried the unvaccinated.

I have buried a beloved child of God in a cemetery in the rain (with no tent or umbrella) on Good Friday when the cemetery would allow only one family member to attend. I watched water dribble off the casket.

(123rf.com)

I remembered learning at Asbury that the God who calls also accompanies us — even in the most unimaginable, bizarre moments of ministry. Perhaps that’s why early in the pandemic, when a funeral director called at the last minute and said, “Is there any way that you …” I heard in my mind the great Wesleyan hymn, “To serve the present age, my calling to fulfill.” My “present age” was that Good Friday morning at 10 a.m.

Other clergy had said no to the funeral home. It was Good Friday and they had to prepare for services. And early in the pandemic there were a lot of unknowns about transmission. Who had that one griever been exposed to? Who had the cemetery workers been exposed to? Who had the vault delivery man been exposed to? Who had the florist been exposed to?

I immediately said “yes” to bury an elderly stranger because I had learned at Asbury that Asburians show up.

I have tried my best, given my training at Asbury, to serve individuals in their vulnerable moments; some individuals are from the LGBTQ community and are well aware of Asbury’s bias against them. I have repeatedly pleaded, “Jesus, you have to help me serve this family, this individual in this crisis.”

I cannot forget Jesus’ words to his judgmental disciples, “Do you see this woman?” To conduct the service for this 20-year-old who had relapsed unfortunately with bad fentanyl, I nearly wore my voice hoarse pleading “Jesus, help… .”

Why this matters

It is possible — more than just possible — that people will die because of exposure to COVID-19 in the petri dish that is an educational institution like Asbury Seminary or Southern Seminary.

Where have professors recently traveled to speak, preach or attend a scholarly conference? Where have students traveled recently? Have some traveled to student pastorates or to work in youth or music ministries?

If they work in politically conservative churches they have been — and will be — exposed to the proud-to-be-unvaccinated and anti-vaxxers. And they will return to their seminary classrooms as carriers of disease.

In Kentucky (where both schools are located) only 52% of the population has received at least one dose of vaccine. Asbury is located in Jessamine County, with only 57% vaccination; Southern Seminary is located in Jefferson County, which has a vaccinate rate of 68%.

Might epidemiologists eventually identify Asbury or Southern as hotspots of infection —which can be done through scientific tracing — that led to a death or deaths in 2021 or 2022 winter? Surely the boards know these viruses can be traced.

“Does not a seminary have a higher responsibility to provide a ‘safe’ environment?”

Does not a seminary have a higher responsibility to provide a “safe” environment?

I was appalled to read Southern Seminary’s instructions for “Back to Campus: Fall 2021,” which said: “Masks and face coverings will be optional.” I even called the school to see if that statement had been revised: Nope, it has not. More troubling still was this statement: “There will be no return-to-campus testing nor any routine testing throughout the semester.”

I wonder how many times over the decades someone has preached in Asbury’s chapel on Jesus’ words about caring for “the least of these.” If the world is John Wesley’s “parish,” what would he say about the 5 million who have died in this pandemic?

I realize there are Asburians who know the fine minutiae of Wesleyan theology. I do not. I would love to hear them explain suing the federal government over a mandate designed to reduce infection, contagion and save lives.

I have been blessed over the years to have so many ministry colleagues who were graduates of Southern Baptist institutions and, in particular, Southern Seminary. I only somewhat understood their grief for the institution they had attended and had loved. They had grieved for godly professors who had been run off by heresy-sniffers. They are alums of an institution that bears little resemblance to its historic origins. More than a few alums apologized by saying, “I graduated from Southern before … .”

Now, I understand. I graduated from the Asbury Theological Seminary before they sued the federal government to protest an effort to save lives during a global pandemic.

Harold Ivan Smith is thanatologist and independent scholar. For 18 years he served on the teaching faculty of Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. He earned graduate degrees from Scarritt College, Vanderbilt University, and a doctor of ministry degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. His writings include A Decembered Grief, On Grieving the Death of a Father; Grieving the Death of a Mother; When You Don’t Know What to Say; When a Child You Know Is Grieving, When Your People Are Grieving: Leading in Times of Loss.

Related article: