The unexpected spiritual events that recently transpired at Asbury University’s Hughes Chapel in Wilmore, Ky., have captured the attention of thousands upon thousands of Christians and non-Christians all over the world.

The event began Feb. 8 in an innocuous weekly chapel service. The difference is the service did not end at the appointed time. Several students remained in the chapel and quietly prayed, and soon others joined them.

This flowed into a continuous worship service led not by the faculty, staff or the chaplain, but by Asbury students. The service has continued almost two weeks and would most certainly last longer had the university administration not decided to end the on-campus aspect Feb. 24.

Although I have not been able to attend, I have watched hours upon hours of the event via livestream, read dozens of testimonies on social media and listened to my students at Campbellsville University who made the hour trip to Wilmore to experience what has been described as a manifestation of the Holy Spirit.

Concerns and trepidation

Before I began watching and hearing the testimonies, I had concerns and felt some trepidation. I have been a theology professor on Christian college campuses 22 years and feared there would be lack of theological depth and too much emotional manipulation. I’ve seen it happen before.

I expected smoke machines or light shows meant to stir the students to an emotional frenzy. They were not present. I expected the praise songs to be shallow, and some were, but most were theologically sound. Some participants were emotional, but the Holy Spirit often works through our emotions. I was happy to see the service was marked by personal confession, corporate and private prayer, testimonies, praise and worship.

God is most certainly doing something at Asbury, but what? Is it a revival? Is it an awakening?

God is most certainly doing something at Asbury, but what? Is it a revival? Is it an awakening?

A revival usually begins when a local church decides to dedicate several services designed to promote spiritual renewal and lead souls to Christ. The services usually are highly anticipated, announced well in advance and led by a guest evangelist who specializes in such events.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, these services lasted several hours a day, occasionally were nonstop and could continue for weeks. Today, they usually are limited to an hour or two and rarely last more than five days.

Signs of true revival

What are the signs of a true revival? Fortunately, Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758), America’s first and greatest theologian, provides his opinion in his 1741 work, The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God: (1) Jesus is exalted. (2) The Holy Spirit acts against the influence of Satan’s kingdom by preaching sin and repentance. (3) The Bible is exalted. (4) Sound doctrine is prevalent. (5) The love of God and other people is promoted.

An awakening occurs when many revivals spontaneously begin in the same general time frame and spread across a large area, manifesting in many salvation experiences and rededicated and changed lives.

As a professor of church history and theology, I believe examining the past might cast light on what has been occurring at Asbury. This is best done by examining other events in American Christian history that have been depicted as a powerful revival or awakening to see if there are any similarities or differences, and if Edward’s “Signs of True Revival” occurred in Wilmore. This examination is in no way complete and exhaustive.

The First Great Awakening (1720-1740) was America’s first great spiritual event that covered much of the nation. The ministers who led these services were Calvinists, preached on the importance of spiritual renewal, the necessity of a new birth, the importance of having a testimony and certainty in one’s salvation. Although emotional responses were reported, they would not be considered emotional in the 21st century.

A revival or awakening often begins in times of anxiety or stress that leads to prayer for a change in the status quo …

A revival or awakening often begins in times of anxiety or stress that leads to prayer for a change in the status quo, and the First Great Awakening was no different. The first wave of Puritans who came to New England in the first half of the 17th century were zealous in their beliefs and hoped to create a Christian commonwealth in the New World.

Their children, however, were not as zealous, and religious affections began to decline in the second half of the century. Puritan pastors led their congregations to pray this nadir of spirituality would end.

Their prayers were answered beginning in 1726, when a Dutch Reformed pastor, Theodore Frelinghuysen (1691-1747), in the Raritan Valley of New Jersey began to deliver sermons that stressed true Christians lived godly lives and could recount their conversion experience. Hearts were stirred, and revival began to spread from church to church.

Emotionless sermons, passionate responses

In 1734, Jonathan Edwards, pastor of North Hampton Congregational Church in Massachusetts, began to preach sermons on the need for a new spiritual rebirth. His emotionless sermons received passionate responses of repentance, and a revival began that spread throughout much of the Connecticut River Valley.

Preaching in England and America, George Whitfield (1714-1770) was the First Great Awakening’s most influential evangelist. In 1740, he preached 130 sermons on repentance and sanctification from New England to Georgia. Thousands of people attended his services. An excellent orator with a strong charisma, Whitefield even impressed a deist named Benjamin Franklin.

The First Great Awakening resulted in an increase in morality and public decency. An estimated 40,000 people joined New England churches, and thousands more joined churches in the middle colonies.

Unlike the First Great Awakening, the Second Great Awakening featured a move away from predestinarian Calvinism and toward a free will Arminianism. It involved three distinct phases. The first occurred at Yale College and affected New England Congregationalists. It was localized. The second occurred on the western frontiers of Kentucky, Missouri and Tennessee. Charles Finney (1792-1875) and his revivals dominated the third phase.

Little in common

The second, or western, phase of the Second Great Awakening had little in common with the orderly First Great Awakening. It featured generally uneducated ministers, rambunctious services and Arminian soteriology, consistent with the emerging American belief that individuals could write their own destinies.

The 1801 Cane Ridge Revival in Bourbon County, Ky., epitomized this phase of the Awakening. Barton Stone (1772-1844), pastor of a small Presbyterian church in Cane Ridge, announced, well in advance, a communion service would be held at his church with Presbyterian, Baptist and Methodist ministers participating.

Accounts vary, but the six-day revival may have attracted as many as 25,000 people. They came from great distances and camped in the field near the church. The ministers examined the candidates for the Lord’s Supper, and many were found unworthy and became distraught.

The Cane Ridge Revival led to the popularity of emotional services with the intent of conversion and rededicating one’s life to Christ.

Ministers began to preach highly emotional sermons meant to bring those denied communion to repentance. Many of these people began to bark like dogs, faint and have convulsions. The Cane Ridge Revival led to the popularity of emotional services with the intent of conversion and rededicating one’s life to Christ. It also led to the rise of populist denominations, such as Baptists and Methodists, and the birth of the Pro-Revival Cumberland Presbyterian denomination.

The third phase launched the rise of the professional, famous evangelist who leads revivals that are well-announced in advance, often take place in large cities, and conversion experiences are the emphasis more so than spiritual renewal, although it is not totally absent.

Charles Finney is the father of the modern revival service. An ordained Presbyterian minister and dramatic pulpiteer, Finney was saved in 1821, when he went to the woods and prayed for salvation. He said he experienced a vision of Christ and received baptism of the Spirit. This event taught him anyone could come to Christ.

Between 1827 and 1832, Finney held revivals in New York, Philadelphia and Boston. In these meetings, Finney introduced his “New Measures.” He would announce his services well in advance to ensure a large crowd and hold it for several days to help gather momentum. He also would call out known sinners by name from the pulpit.

He allowed women to speak or preach and most famously invented the “anxious bench.” Finney reserved the first bench for those who were “anxious” about their spiritual condition. Those who were led to pray for these souls would come forward and pray with them. The anxious bench was a clear precursor to “coming forward” that is prominent in many evangelical denominations today.

Human means

Finney had no problem using human means, some bordering on unethical, to bring people to Christ. Finney’s manner of holding a revival had a great effect on how revivals were held in the late 19th and 20th centuries, as demonstrated in the revivals/crusades of D.L. Moody (1870-1922), Billy Sunday (1862-1935) and Billy Graham (1918-2018).

The Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles from 1906 to 1914 left a lasting mark on revivalism and American Christianity.

The Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles from 1906 to 1914 left a lasting mark on revivalism and American Christianity.

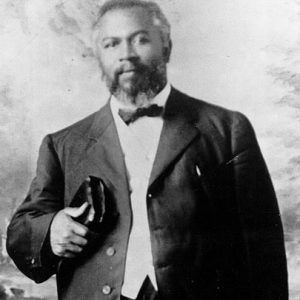

William J. Seymour

On April 6, 1906, Pastor William Seymour (1870-1922) was ministering in Los Angeles when he and seven others claimed to be struck as though by lightning and immediately began to speak in tongues. News of the event spread quickly, and soon the building where their services were held proved too small to accommodate the large number of attendees.

Baptists, Methodists, Quakers and members of Holiness churches soon joined the services, which were marked by emotional preaching and a necessity of being baptized in the Holy Spirit. Attendees claimed to witness miraculous healings, speaking in tongues and people being thrown to the floor by the power of the Holy Spirit. Many Pentecostal groups and denominations resulted, such as the Apostolic Faith Church, Church of God in Christ, and several other Wesleyan-Holiness denominations.

Similarities and differences

The spiritual event occurring at Asbury has many similarities to and differences from previous revivals and awakenings.

Unlike the planned revivals of the Second Great Awakening, the Asbury outpouring was spontaneous. By all accounts, when the initial chapel service concluded, several students were compelled by the Holy Spirit to remain and pray.

It is not driven by the popularity of prominent evangelists. The event is being led by students.

It does not appear to be taking unethical measures to portray a successful revival. One of my former students, Fontez Hill, student ministry pastor at Church of the Savior in Nicholasville, Ky., who has volunteered at Asbury, assures me nothing manipulative has occurred, and measures have been taken to ensure manipulation will not happen. Moreover, several dubious evangelists have attended the services and in no uncertain terms were told they could attend and worship but nothing more.

Although some charismatic displays have occurred — and there is nothing wrong with it — nothing compares to the Azusa Street Revival. There is nothing on the level of the uncontrolled chaos of the Cane Ridge Revival.

Another of my former students, Pastor Jon Proctor of Bethesda Community Fellowship in Russell Springs, Ky., has seen nothing to lead him to believe this meeting is remotely charismatic.

“At Asbury, the attendees and the students aren’t coming there with a set expectation of what church or chapel is supposed to look like. They have a unified purpose to wait for God’s presence, and that’s the reason I believe God’s meeting them there,” he said. “It’s tangible. It’s special. You know that I’m Pentecostal, and this didn’t seem like a Pentecostal move.”

God glorified

God has been glorified. One of my current students, Kelsey Overall, described it as an amazing movement of the spirit. “We were able to just authentically worship. Lights were fully on. Voices louder than the mics,” Kelsey said. “This was pure. This was real. You could just look around, and there were people from everywhere, and every age. There were people down on their knees being prayed over in the front. People sitting and reading the word. Others standing in worship. Some screaming with joy. It was a healthy, chaotic environment.”

The outpouring at Asbury has commonalities with past revivals, but in reality, it is different from all of them.

The outpouring at Asbury has commonalities with past revivals, but in reality, it is different from all of them.

It most resembles the Asbury Revival of 1970. It, too, was led by students, God was praised, it was “healthy chaotic,” lasted a good long while, spread to several different places with the same effect, and lives were changed by the Holy Spirit.

Like today’s experience, the Asbury Revival of 1970 received guests from all over the United States who were filled with the Holy Spirit and returned home with the desire to see God work on their campuses and churches. The current Asbury spiritual experience has not contradicted the Bible. It has changed lives, relationships have been restored, and Christ has been magnified.

It appears these characteristics are occurring at Asbury. Whether it is the next American Great Awakening, only time will tell. Like those who attended the 1970 Asbury revival, many of those who have attended 2023 services have returned to their homes, told of their experiences, and similar events have been reported on several Christian campuses.

What I do know and believe with all my heart is something wonderful and of God is happening at Asbury University, and Jonathan Edwards would approve.

Joseph Early is professor of church history, theology and ethics at Campbellsville University in Campbellsville, Ky. He is the author of eight books, including The Life and Writings of Thomas Helwys, A Texas Baptist Power Struggle and Introduction to Christian History.

Related articles:

What I experienced this week at the Asbury revival

About the Asbury ‘revival’: Time will tell

Questions to ask while pondering if Asbury is hosting a ‘true revival’

Asbury University closes down revival that clogged small Kentucky town