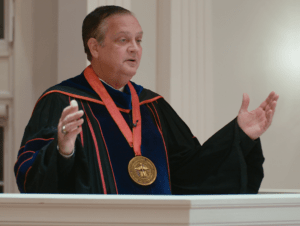

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary board of trustees simply adhered to biblical principles in voting to keep the names of slave-holding founders on campus buildings, President Al Mohler said.

Just as the Bible retains the names of imperfect, sinful leaders like Abraham, Moses and King David, so the seminary will do with the names of James P. Boyce, its first president, and founding faculty members John Broadus, Basil Manly Jr., and William Williams, Mohler said in a news release after the unanimous vote by trustees Oct. 12. He made a similar case in an eight-page report to trustees about the issue.

These men played an invaluable role not only in launching the seminary but also in matters of doctrine and teaching that continue to be of value today, he said.

Seminary President Al Mohler

“We stand in conviction on the great truths of the Christian faith and in confessional agreement with our founders. Their theological orthodoxy and Baptist confessionalism are an invaluable inheritance, and we stand with them in theological conviction, period. But we deal honestly with their sin and complicity in slavery and racism.”

Trustees also voted to pursue ways to lament the seminary’s racist past and to fund $5 million in scholarships for Black students.

“We must be clear in our heartbreak and horror in the face of racism and racial supremacy,” Mohler said.

‘A fruit worthy of repentance’

The trustee action was not well-received by other Baptists who have made a case for purging the seminary’s buildings of names associated with slaveholders and those who enabled slavery.

Prominently displaying the names of slaveholders and offering a scholarship hardly amounts to repentance, said Joe Phelps, co-chair of Empower West Louisville and Highland Baptist Church, located a short drive from the seminary campus.

Joe Phelps

The trustees’ decision is little more than an effort to find theological justifications to inaction, Phelps said. “Don’t just say you’re sorry. Make amends. Do the right thing.

“Dr. Mohler and his minions are equivocating because they aren’t able to do the right thing, they aren’t able to own their own sin and the sin of Southern Seminary and the sin of the Southern Baptist Convention,” Phelps declared.

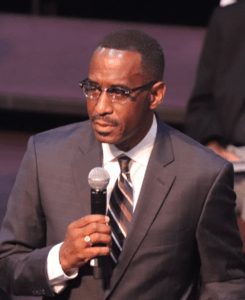

Dwight McKissic, pastor at Cornerstone Baptist Church in Arlington, Texas, and one of the Southern Baptist leaders who previously raised the issue with the seminary, questioned the logic Mohler and the trustees used to explain their vote.

“It remains my deep conviction that there is a moral inconsistency with the orthodox Christian faith that cannot reconcile the celebration and honoring of men stealers and child abusers with the inerrant and infallible word of God,” he said in an Oct. 13 blog post.

Dwight McKissic

McKissic, who is Black, led a months-long campaign to remove the slaveholders’ names from seminary facilities and is well known for convincing the Southern Baptist Convention to pass resolutions denouncing the Confederate flag, the alt-right movement and white supremacy.

Southern Seminary was founded in 1859 in Greenville, S.C., and moved to Louisville, Ky., in 1877. The founders’ names are affixed to buildings such as Boyce College, Broadus Chapel and Boyce Library.

McKissic wrote to Mohler last week asserting that preserving those names will not, as Mohler claims, help recall the evils of racism.

“By allowing the names of the founders to continue to be plastered on walls and memorialized publicly as men of high moral character — you are in effect upholding their legacy of being theological and practical proponents and defenders of white supremacy and Black inferiority,” McKissic charged.

He also predicted the decision will not last indefinitely. “The next generation will not accept this moral inconsistency and will change the names of these unrepentant abusers of mankind.”

McKissic praised the trustees for voting to establish a scholarship in the name of Garland Offutt, Southern’s first Black graduate.

However, McKissic praised the trustees for voting to establish a scholarship in the name of Garland Offutt, Southern’s first Black graduate. Offutt earned a master of theology degree in 1944 and a doctorate in 1948.

“It certainly represents fruit worthy of repentance. It speaks to the past and to the future,” he said on Twitter. In another tweet he said: “Hats off to Dr. Mohler and the trustee board for this historic decision that is a step toward healing.”

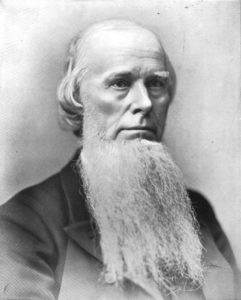

Vacating a chair

That step was about two years in the making. The seminary issued a report in 2018 on the role of slavery and racism in its then 159-year history. The 71-page document reported that Boyce, Broadus, Manly and Williams owned 50 slaves between them. It found that the early faculty and trustees “defended the righteousness of slaveholding” and that the seminary backed the Confederacy’s goal of preserving slavery. Boyce served in the Confederate army in which Broadus was a chaplain.

In addition, the report revealed that Joseph E. Brown, a key donor to the seminary and chairman of its trustees from 1880 to 1894, earned a significant portion of his wealth through the exploitation of Black convict-lease workers even after emancipation.

Joseph Emerson Brown

As president, Mohler previously was named to the Joseph Emerson Brown Chair of Christian Theology, another sticking point for seminary critics on racial justice. At this week’s meeting, trustees declared that chair vacant and elected Mohler to a new chair, the Centennial Chair of Christian Theology.

Speaking to trustees about Brown, Mohler said: “We must ask whether any name is wrongly commemorated in our institutional life. We do not get to choose a history, but we do bear responsibility for who we commemorate and why.”

Trustees unanimously agreed to vacate that chair, a logic that appeared contrary to their decision on building names. In his report to trustees, however, Mohler made a distinction regarding the founders, comparing them to Washington and Jefferson in founding the United States.

“Is the burden of history and the blessing of heritage best served by removing the names of the founders?” Mohler asked. “I believe not. Instead, I believe it would lead to Southern Seminary becoming a very different institution, and one that is less faithful in doctrine and confession.”

Previous calls for reparations

In 2019, the seminary publicly lamented its racist past but refused to make monetary reparations to nearby Simmons College of Kentucky, a historically Black college founded by slaves. Empower West promoted a petition on Change.org.

Kevin Cosby

“Please sign this petition calling for the Southern Baptist Seminary to pay reparations for their crimes against humanity,” Kevin Cosby, Simmons College President and a leader of Empower West, said via social media in June that year. “Southern was started by slave owners for the purpose of maintaining slavery. They like no other institutions gave the theological rationale for slavery and Jim Crow.”

The petition enjoyed strong support in progressive Baptist circles, with signatories including Molly Marshall, then-president of Central Baptist Theological Seminary; Curtis Freeman, director of the Baptist House of Studies at Duke University; Bill Leonard, founding dean of Wake Forest University Divinity School; and Linda McKinnish-Bridges, former president of Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond.

Mohler shot down the idea, however, saying the SBC would not permit the seminary to transfer money to another institution — especially one that does not share its interpretation of theology and Scripture.

“We’re not going to respond to public demands for reparations made, quite interestingly, by the people who demand that the reparations be paid to them,” Mohler told Religion News Service at the time. “And, furthermore whatever we do, this institution will do in keeping with its theological commitments.”

Cosby, senior pastor at St. Stephen Baptist Church in West Louisville, again took to Twitter. “How convenient, the institution that created the crime gets to determine what the consequences should be!”

Calvinist call for retaining names

The issue of Southern’s racist roots rose to newsworthy levels again just ahead of the trustees’ action when a group of white Calvinists, including retired seminary professor Tom Nettles, rushed to the defense of the four founders and of slavery itself, Baptist News Global reported in September.

Nettles argued that “antebellum slave owners” and “post-bellum white supremacists” aren’t “necessarily heretical.”

He also defended slavery as having biblical support. That it is wrong for slaves to escape is a position justified “in biblical infallibility and in the revelatory ministry of the apostles,” he added.

The Calvinists also claimed that removing the founders’ names from seminary facilities would diminish their positive contributions to the institution and to Christianity.

McKissic disputed that argument, saying the slaveholding founders’ don’t have to be attached to buildings to be remembered.

“I am merely arguing for the removal from their current place of honor the names of Boyce and others who bought, sold, or continued to hold kidnapped human beings precisely,” McKissick wrote to Mohler.

‘Both saint and sinner’

Mohler made it clear following the Oct. 12 vote that the seminary is firm in a course that is in keeping with Christian history.

“The church, beginning with the Apostles, has been led by pastors, taught by preachers, and nourished with the blood of the martyrs. Every one of these human beings is, as a believer in Christ, both saint and sinner. Our task is to honor the saintly without condoning, hiding, or denying the sinful,” he said.

McKissic said the sin of the founders cannot be overlooked.

“They did such a good job of instilling the sin of white supremacy and Black inferiority into the fabric, theology, policies and image of the school, until it was almost 100 years later before a Black student was admitted to SBTS,” he said. “Is it really fair to ask this generation to honor these men in light of their heterodoxy and immoral lifestyles?”