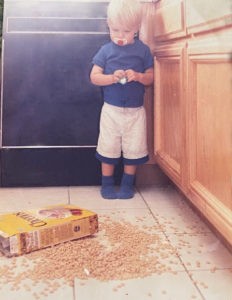

During the mid-1990s, I was a sleep-deprived mother of a newborn and a toddler, a wife, a college professor, and a doctoral student with an unfinished dissertation. While zombie-walking through mundane chores, I heard the contents of the last box of Cheerios dance on the tile of my kitchen floor. I discovered Sam, my toddler, nestled into a corner, his head not tall enough to reach the countertop. He surveyed the cereal spatter patterns like a weary, seasoned detective working a crime scene.

To prepare his meal without adult assistance, he reached for something that he could not see. But unfortunately, his ambition exceeded his abilities, creating mishaps in plain view. Even with an adult to the rescue, there was no way we could get those Cheerios back in the box.

I captured Sam’s predicament on film, wanting to remember the purity of his embodied feelings and thoughts. He was authentic and expressive in his distress. Yet, he focused on problem-solving without distortions of guilt and shame.

I captured Sam’s predicament on film, wanting to remember the purity of his embodied feelings and thoughts. He was authentic and expressive in his distress. Yet, he focused on problem-solving without distortions of guilt and shame.

Sam soothed himself with two pacifiers, bobbing one in his mouth, kneading the other in his tiny hands as he pondered his next move. I saw a child instinctively adapt to a missed mark the way I hope we do as adults, with heart, body and mind showing up to self-comfort, appraise and repair.

It seems like there are lots of Cheerios on the floor these days. We long to resume cherished routines of school, work and other delayed communal life celebrations without fear of disease. We sacrifice in hopes of winning a 20-year war in a faraway land. We battle to extinguish fires, subdue floodwaters and end a drought.

But we can’t always get the Cheerios back in the box. So how do we soothe ourselves as we endure and repair the mishaps that shape our lives?

I am curious about the self-comforting strategies Jesus used as he navigated exasperating situations. We know of many instances when Jesus met the needs of others, often at his expense. We have favorite examples that include feeding thousands of undernourished peasants, serving the best drinks at a wedding, comforting disciples during a storm, and restoring the life of his friend Lazarus. But I am less aware of how Jesus took care of himself, soothed himself and asked for help when he faced challenges.

The Gospels tell us that Jesus ditched the demanding herds, retreating into solitude. He visited trusted friends who loved him, fed him and provided a restoring resting place. I imagine he was allowed to control the TV remote and sit in the best reclining chair when hanging out with Mary, Martha and Lazarus. He told others when he was tired and hungry, asking for food and drink. Jesus shared his disappointments when his friends failed to be honest, present or loyal. He wasted no emotional bandwidth on harbored resentment or dwelling on the small stuff. Jesus let people know when his nerves frayed. He napped.

I believe Jesus asked people around him to care for themselves as a way of teaching them about love. His uncanny connection to others and their pain was one of his greatest gifts. When people asked to be healed, Jesus treated each wound uniquely, according to the person’s need. He also invited people to participate in their own healing, washing one’s own diseased body, returning to those who rejected them, picking up a sickbed, and walking away from the begging place. Jesus taught that self-love was an inseparable part of loving God.

Have we neglected this elegant part of Jesus’s life and work? Does our theology include the wholeness of nurturing ourselves as we care for others?

“Does our theology include the wholeness of nurturing ourselves as we care for others?”

Maybe we need to explore this dimension of Jesus, one who gave generously, not only to others but to himself. This could be counter-intuitive to our understanding of the suffering Savior. Yet Jesus lived in love, not obligation or guilt. He reminds us that our value comes from who we are as God’s beloved, not our productivity or social capital. Our mistakes, disease and spills can be portals that allow us to discover who we really are amid the love that always has awaited us.

We are the primary stewards of our sacred temple, tending it carefully as part of our calling. Caring for ourselves is a compassionate act, an enactment of God’s love. We have more to offer when our emotional storehouses abound, allowing us to be more attuned to the needs of others. We learn our boundaries, the things we want that are beyond our reach, connecting us to the talents of others.

Loving and caring for ourselves, particularly when we “spill it,” frees us from the grasp of perfection. It takes attention and intention to learn the dance of self-love and loving our neighbor. But it may be the best prom we ever attended.

My toddler is now 29 years old. Sam, his brother and I have many opportunities to self-soothe and sweep up our spills. I share Sam’s image and story with his blessing.

Paula Mangum Sheridan

Paula Mangum Sheridan recently retired from Whittier College as an associate professor and program director of the social work department. She is a licensed clinical social worker and supports voter accessibility and the rights of people without homes in her community.

Related articles:

Self-care as political resistance – or how (not) to sacrifice humans to ‘save’ the economy | Opinion by Eric Minton

10 ways to take care of yourself because things may get worse before they get better | Opinion by Rhonda Abbott Blevins

Ten reasons for hope in this time of dystopia | Opinion by Susan Shaw