Special occasions like Easter, spring teas and mature weddings find many women shopping for hats. I’ve lived all my life in Northern California and love wearing hats to these events. But I’m definitely in the minority here. If you’ve ever stepped into a unanimously hatless congregation on Easter morning well, you and I should meet for afternoon tea sometime — wearing our hats.

In some U.S. areas, modern denominations have loosened the traditional custom of Christian veiling. I understand, though, that hats are more welcomed in churches in the South, and that culture plays an important role. For Black women, they’re not just a fashion statement; a look at history reveals the deep significance of this connection.

Phawnda Moore

I’m among those who have humbly realized that a wardrobe accessory to some can be a symbol of a long, painful struggle for generations of others.

Hats for Black women have come to illustrate the strength and beauty that has blossomed out of their resilience, from their forcible capture in Africa and transport over the Atlantic Ocean, through enslavement during the 17th to 19th centuries, to the challenges faced today.

When masters shaved their heads to dehumanize them, they also removed the African pride in adorning their hair with intricate braids, shells and beads. These cultural hairstyles had long identified a person’s marital status, age, religion, ethnic identity, wealth, geographic origin and the clan to which they belonged.

In the years that followed — during Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s — hats (“crowns”) became hallmarks for women’s faith and spirit, restoring their dignity, confidence and self-worth, at least to themselves.

However, despite some progress, modern society then discriminated against Black natural hairstyles, particularly at work and school. This bias is currently being addressed with state laws.

In 2019, California was the first state to pass the CROWN Act, an acronym for Create a Respectful and Open Workplace for Natural Hair.

Twelve states followed, and the U.S. House of Representative passed CROWN Act legislation in March 2022. “The act would prohibit discrimination based on natural and protective hairstyles associated with people of African descent, including hair that is tightly coiled or tightly curled or worn as locs, cornrows, twists, braids, Bantu knots and Afros.”

Supreme Court nominee Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson testifies during her confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee March 23, 2022 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

Most recently, Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson proudly shared the meaning of her given African name, “lovely one,” wearing a sisterlocks hairstyle, as she’s being considered for Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.

Along with exceptional role models, seeing hats in museums brings greater awareness. When a past exhibit of “Extraordinary Crowns” opened at The Harrison Museum of African American Culture in Roanoke, Va., local residents contributed memories. Guy Smith, whose mother owned more than 150 hats (some are on display at the museum) recalled, “They would do different things with wraps they would wear in the field, (including) different straw hats so they could express themselves.”

“Hats are an expression of the Black women’s belief about themselves even when the messages from society told them otherwise,” he said. “The hats … symbolize triumph over hardship.”

To better understand the history of the Black experience, including the desperate voices of slaves, and even the role of hats in it, visit the online access of Smithsonian artifacts, stories and images where “digital visitors can see the shawl given by Britain’s Queen Victoria to the famous underground railroad conductor Harriet Tubman, as well as a simple straw hat owned by the civil rights and bus boycott leader Rosa Parks.”

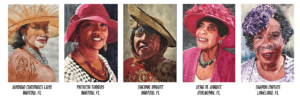

Some of the watercolors in the new exhibit by Ronald Malone.

Black women and their church hats continue to gain interest in America. Ronald Malone, a portrait artist in Barstow, Fla., was inspired to paint local women wearing beautiful hats, their “Sunday best.” This year, his 20 portraits went on exhibit at The Polk County History Center in Barstow in recognition of Black History Month, and the display continues until August 2022.

The Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of African American History and Culture tells an amazing story of famed Philadelphia milliner Mae Reeves, a pioneer who left her Georgia home in 1934 to seek economic security at a time it didn’t exist for many. She called her creations “showstoppers.” Whether they were covered in vibrant flowers, adorned with delicate beading, or emblazoned with a brooch, the hats created in Reeves’ shop were nothing short of wearable art. Now on permanent display, The Power of Place showcases more than 60 of her stunning original creations in the City of Brotherly Love, where she made her home.

Many, unaware of the reality of Black slaves’ lives or subsequent times, question why all this matters today. The late African American poet Maya Angelou said, “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived; but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Angelo wrote the foreword to Crowns: Portraits of Black Women in Church Hats. After reading stories from spirited, sassy and inspiring evangelists to Civil Rights marchers to law professors and teachers, I’m off to buy a new hat!

On Amazon, I found this notice: “Photographer Michael Cunningham beautifully captures the self-expressions of women of all ages — from young glamorous women to serene but stylish grandmothers. Award-winning journalist Craig Marberry provides an intimate look at the women and their lives. Together they’ve captured a captivating custom, this wearing of church hats, a peculiar convergence of faith and fashion that keeps the Sabbath both holy and glamorous.”

Generations of women reminisce about their relatives’ hats as a meaningful sisterhood. In many churches, hat stories and conversations form a bond of community. Listening to and understanding the Black woman’s hat testimony can bring us all closer to a place of grace in America.

Phawnda Moore is a Northern California artist and award-winning author of Lettering from A to Z: 12 Styles & Awesome Projects for a Creative Life. In living a creative life, she shares spiritual insights from traveling, gardening and cooking. Find her on Facebook at Calligraphy & Design by Phawnda and on Instagram at phawnda.moore.

Related articles:

From the war in Ukraine to the slap in Hollywood, violence plagues our world | Analysis by Laura Ellis

Pastors, will you speak up when a Black woman is demeaned? | Opinion by Frederick Douglas Haynes III and Ralph Douglas West