Tony Campolo, an influential Christian pastor, professor, author, speaker, social activist and adviser to President Bill Clinton, died Tuesday, Nov. 19 at age 89.

He was surrounded by family at Beaumont at Bryn Mawr, the Philadelphia retirement community where he and his wife, Peggy, lived since 2006, following a debilitating 2020 stroke that abruptly ended his speaking career.

Campolo will miss next February’s planned combo celebration of his 90th birthday, the 10th graduating class from the Campolo Center for Ministry at Eastern University, the 100th anniversary of Eastern, where he taught for decades, and the publication of his 50th book, Pilgrim: A Theological Memoir, which I helped him write over the past three years.

“Tony’s professional legacy is profound,” said an obituary posted on the Campolo Center’s Facebook page. “Tony touched countless lives around the world with his hopeful message of social justice, love, and reconciliation.”

“Throughout his life, Tony was a shining example of kindness, exuberance, authenticity and commitment, and he leaves behind a wonderful legacy of evangelical scholarship, inspirational communication and missionary impact.”

Born in 1935 to a poor Italian immigrant family in Philadelphia, Campolo got his speaking ability from his mother and his compassion for the poor from his hard-working father.

While appreciative of his strict fundamentalist upbringing, he ultimately rejected its legalism and anti-intellectualism, becoming a popular evangelical speaker who raised millions in donations for ministries including Compassion International and World Vision. He was a bestselling author whose books were turned into films, and he was a regular critic of the influence of the Religious Right and the growing politicization of evangelicalism.

Campolo was awakened to the harmful power of racism at age 16 when his family’s church, New Berean Baptist, refused membership to a Black woman in 1951. This scenario repeated itself in the 1960s at a church Campolo served as pastor, Upper Merion Baptist Church in King of Prussia, Pa. When elders in his church refused to admit the woman, Campolo resigned his pastorate, convinced he had failed as a pastor.

Campolo was awakened to the harmful power of racism at age 16 when his family’s church, New Berean Baptist, refused membership to a Black woman in 1951. This scenario repeated itself in the 1960s at a church Campolo served as pastor, Upper Merion Baptist Church in King of Prussia, Pa. When elders in his church refused to admit the woman, Campolo resigned his pastorate, convinced he had failed as a pastor.

He had his heart set on attending Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky., but his father’s failing health forced him to stay closer to home, attending Eastern University, where he met Peggy Davidson, a pastor’s daughter who had vowed not to marry a pastor. They wed in 1958 and had two children: Lisa, an attorney, and Bart, a counselor, who were at his side when he died.

After resigning his pastorate, Campolo applied for a teaching position at Eastern, which hired him in 1964, and he joined a Black church, Mount Carmel Baptist, where he loved the church’s preaching style and enthusiastic worship.

At a preach-off between Black pastors at Mount Carmel, Campolo heard his pastor, Dennie W. Hoggard, deliver a memorable message titled, “It’s Friday, but Sunday’s Comin’.” Campolo adopted Hoggard’s talk as his own, creating one of his best-known sermons.

Campolo’s talk was broadcast at Eastertime by Focus on the Family for years, leading to a bestselling book and popular Christian film based on his words.

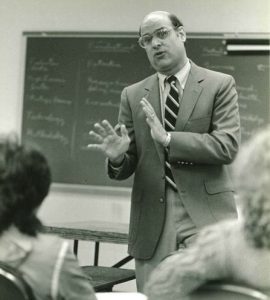

Campolo taught sociology at both Eastern and the University of Pennsylvania during the 1960s. While many evangelicals condemned the excesses of the decade, Campolo cherished the opportunity to teach and mentor students of the “quest generation,” who kept him informed about feminism, sexism and homosexuality — topics he had not studied in depth.

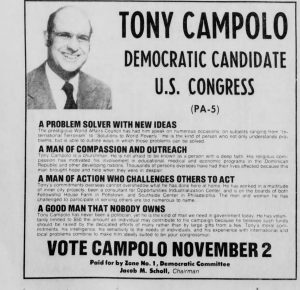

A lifelong Democrat and supporter of labor unions, Campolo ran for Congress in 1976. In 1993, he was invited to meet with newly elected President Bill Clinton, a Southern Baptist who was under fire from fellow Baptists. At the Southern Baptist Convention’s June 1993 gathering, representatives introduced 19 resolutions against Clinton and Al Gore, his vice president and fellow Southern Baptist.

Campolo offered the president faith-based speech suggestions and policy ideas and was one of three pastors who ministered to Clinton during the Monica Lewinsky sex scandal, leading to condemnation from conservative evangelicals. Campolo criticized Clinton’s half-hearted apology and encouraged him to publicly confess his sin and seek repentance. Their relationship lasted for decades.

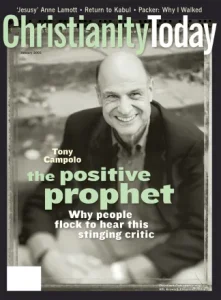

Campolo was a popular speaker at events for Christian youth pastors until 1985 when Campus Crusade for Christ founder Bill Bright canceled his speaking engagement at Youth Congress ’85 and accused him of heresy. A 1985 “heresy trial” organized by Charles Colson found Campolo innocent, but the controversy would lead to a decline in his evangelical speaking opportunities.

In 2007, Campolo helped organize a new group called Red Letter Christians, “a term that signified our commitment to living by the words of Jesus, which in some Bibles are printed in red ink,” he said.

In 2007, Campolo helped organize a new group called Red Letter Christians, “a term that signified our commitment to living by the words of Jesus, which in some Bibles are printed in red ink,” he said.

“Our goal was to create a competing movement that would counteract harmful rightwing policies with constructive, nonpartisan policies that hewed closer to Jesus’ values. But if you look around today, you can see that we fell short in our efforts.”

Shane Claiborne, a former student of Campolo’s at Eastern and co-founder of Red Letter Christians, praised his mentor’s “authentic” and “contagious” faith earlier this month.

“In a world with plenty of counterfeit ‘Christianity,’ Tony shows what it looks like to live as if Jesus actually meant everything he said,” Claiborne said. “Other than the sweet Lord Jesus, I can’t think of anyone who had shaped me spiritually more than Tony Campolo, and I’m not alone when I say that.”

For years, Peggy Campolo taught love and acceptance for LGBTQ people while Tony maintained the Bible was opposed to gay marriage. The couple spoke together at churches, showing how people of good faith could disagree on the issue. But he changed his tune in 2015, just weeks before the U.S. Supreme Court announced its ruling allowing same-sex unions in Obergefell v. Hodges. His announcement further alienated much of his former evangelical support and led to him speaking at more ecumenical and progressive Christian gatherings.

Campolo suffered his first stroke in 2002 following a speaking event in Hawaii, and he and Peggy moved into Beaumont at Bryn Mawr four years later. The loss of his speaking career following his 2020 stroke left him with a “profound identity crisis.”

“I’ve been one of your faithful soldiers,” he pleaded to God. “Why are you allowing me to be shut down like this?”

He continued his ministry where he could, leading Sunday worship services for about a dozen Beaumont residents, and was looking forward to leaving his worn out body and uniting with his Lord.

During my last two weekly calls with a weakened Tony on Nov. 6 and 13, he expressed dismay at evangelicals’ continuing support for President-elect Donald trump and waxed eloquent on the impact of secularism and Harvey Cox’s 1965 book, The Secular City.

Steve Rabey is a freelance writer based in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Related articles:

Mohler says Campolo’s reversal on homosexuality abandons Scripture

Campolo says ‘Red Letter Revival’ seeks to convert evangelicals to social activism

Progressive faith leaders call for renewed attention to 8 principles of faith and democracy