A U.S. Supreme Court that increasingly views freedom of religious expression as an absolute right even amid a global pandemic appears to feel differently about the religious rights of a condemned inmate.

On Tuesday, Nov. 9, the high court heard an expedited appeal from Texas Death Row inmate John Henry Ramirez, who wants his Baptist pastor to be present with him, hold his hand and pray for him while the state injects him with a lethal drug combination. The state of Texas denied that request, but the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear it and stayed the execution temporarily.

The case presents an interesting inflection point for a court that in recent months has gone out of its way to accommodate the requests of evangelical and Catholic Christians to be able to exercise their religious practices without interference, even when public health is at risk or when others might be injured. This is the first such case the court has considered since the majority tilted decidedly conservative, with three justices nominated by former President Donald Trump.

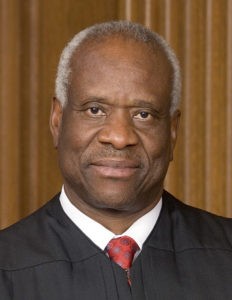

Clarence Thomas

The longest-serving conservative on the court — and the justice historically least likely to speak during public hearings — is Justice Clarence Thomas. In the Texas case, he questioned the sincerity of Ramirez’s religious conviction.

Texas Solicitor General Judd Stone II told the court he believes Ramirez’s request is an attempt to delay his execution. That prompted Justice Thomas to suggest that Ramirez has “changed his requests a number of times” and “filed last minute complaints.” He wondered aloud if the convicted murderer is merely “gaming the system.”

Seth Kretzer, attorney for Ramirez, said that is not the case and that federal law requires the state to accommodate Ramirez’s requests for religious comfort.

The state of Texas has argued otherwise, explaining that it is not logistically possible or safe for Southern Baptist pastor Dana Moore to be present in the small execution chamber or to potentially get tangled in the IV lines that will carry the fatal dose of drugs.

Moore addressed the situation last Sunday with his congregation at Second Baptist Church in Corpus Christi, Texas. The conservative congregation has a long history of ministry to inmates at the Allan B. Polunsky Unit in Livingston, which is more than four hours away. Moore has ministered to other Death Row inmates and has been present as a witness to an execution previously.

Dana Moore

He told his congregation Sunday: “It’s a case about John being created in the image of God, as he is. There’s nothing we do that destroys that image. Treating John with dignity doesn’t take away from anyone else.

“This is not about guilt or innocence. This is not about a loophole. This is about John’s firm belief that he wants me to do my pastoral duty over him in the death chamber.”

In an interview with the Washington Post, Moore insisted he is not being used by Ramirez to delay his execution.

The family of Ramirez’s victim, Pablo Castro, sees it differently. The Post reported that Aaron Castro, the 31-year-old son of the victim, doesn’t believe Ramirez and sees the current court case as “a pure manipulation of the system.”

“This is a guy who killed my father in a horrible, brutal way,” he told the Post. “Did my father have an opportunity to have a priest with him as he moved on to the next life?”

Sincerity of conviction aside, other Supreme Court justices focused on the possible ripple effects of requiring Texas to accommodate Ramirez.

“What’s going to happen when the next prisoner says that I have a religious belief that he should touch my knee? He should hold my hand. He should put his hand over my heart. He should be able to put his hand on my head,” asked Justice Samuel Alito. “We’re going to have to go through the whole human anatomy with a series of cases.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh wondered what a ruling for Ramirez would mean for other inmates and other states in the future. Would all states be required to allow the same exceptions to their protocols on the basis of free exercise of religion?

The Biden administration — which is generally against capital punishment — was represented at court by Eric Feigin of the Justice Department. Based on recent experience with federal executions — 13 were carried out during the Trump administration — Feigin said Texas has a strong argument for not allowing the pastor to touch the inmate during the execution. Officials conducting federal executions have not allowed that, and it would give them “very, very substantial concerns,” he said.

Botched executions always make headlines and provide fodder for death penalty opponents. If the pastor should faint or jostle the IV lines, the outcome could be “catastrophic,” Feigin said.

Sister Helen Prejean

Meanwhile, the morning of the court hearing, The New York Times published an opinion piece by Sister Helen Prejean, a Catholic nun and noted death penalty opponent, who argued that the state of Texas should find a way to accommodate Ramirez’s request. Although she has ministered to numerous people on Death Row, she has been allowed inside the death chamber only once, in 1997, she said.

On that night, the state of Virginia executed Joseph O’Dell. “I stood close to the gurney, looking into Joe’s face, with my hand firmly on his shoulder as I prayed. In my prayer I asked God to affirm Joe’s worth as a beloved son possessing a sacred dignity that even the ones killing him could not take from him,” she explained.

“Upholding the God-given dignity of the condemned has been the core reason I, a Catholic nun, have served as a spiritual adviser to seven men on Death Row. And nothing conveys a greater sense of dignity to a human being — especially one whom society designates as a despicable ‘untouchable’ — than loving, respectful touch.”

There also is theological meaning to this act, she added. “For many Christians, the laying on of hands is at the heart of prayer rituals. The New Testament is filled with examples of touching: Jesus touches a leper and heals him; Jesus takes children into his arms and holds them close; the apostles of Jesus lay hands on religious seekers, empowering them with God’s spirit.”

Allowing the pastor to be physically present with Ramirez would illustrate the Christian belief that all people are made in the image of God and worthy of redemption, the nun said. “I can viscerally feel something of the agony and terror Mr. Ramirez may experience as he is strapped down and killed. From the time of his trial, Mr. Ramirez has received countless signals that he is worth nothing more than disposable human waste.”

She concluded: “I pray that John Henry Ramirez will not die at the hands of Texas executioners. But if he is killed, I pray that his faith companion, Pastor Moore, will be there with him, laying his hands on him, shoring up his dignity, commending him to God.”

There is no indication how long the high court will take to consider the Ramirez case, although as an expedited case, the ruling likely will come far sooner than most Supreme Court rulings, which otherwise can take months.

Related articles:

Final vote sounds the death knell for capital punishment in Virginia

The death penalty is dying a slow death; it’s time we pull the plug | Analysis by Stephen Reeves

What I learned working in a Texas prison: Retribution, not reformation | Analysis by Michael Chancellor