In the evangelical subculture I was raised in, we were taught to cover most of our bodies for the sake of modesty. I was told repeatedly, “Your body is a temple.”

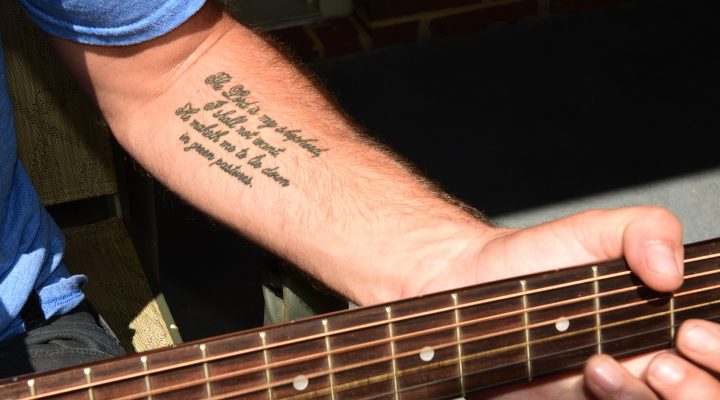

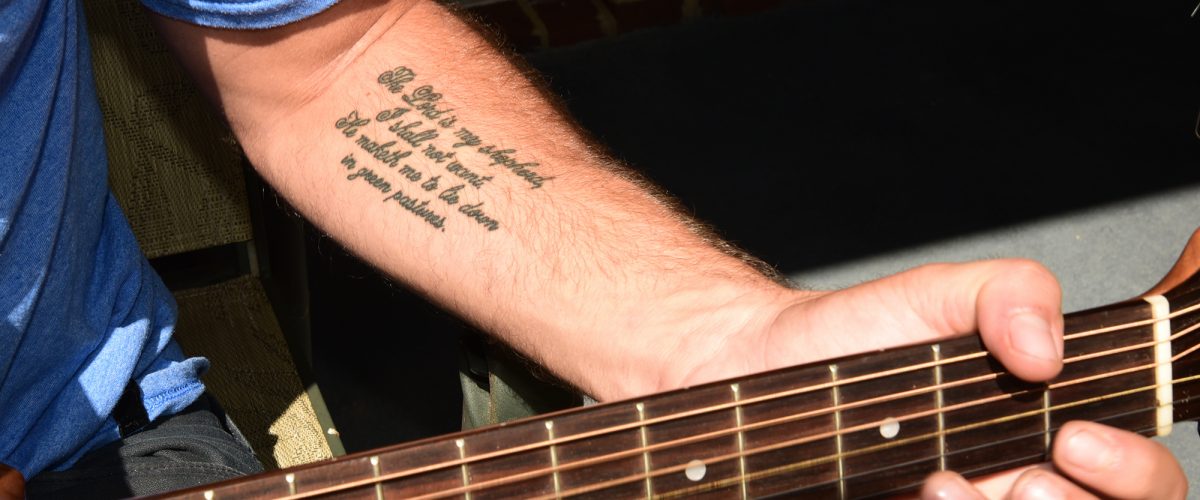

So you can imagine my shock when, as a pre-teen, I found out that worship leaders and staff members at my church had tattoos. I had nothing against tattoos, but I was confused. In my questioning, I more or less gathered from these church leaders that you are not supposed to draw any attention to your body unless doing so allows you to draw attention to your faith. Crosses on your shoulder and Bible verses on your wrist are OK, so long as they reflect the Spirit of Christ. More and more, Christian tattoos became trendy, especially among the older youth and young adults.

Madison Boboltz

I found it poetic that, much like Jesus, the scars of our bodies could tell the stories of our faith. I began to see tattoos as beautiful tools for reflection and evangelism. I expected someday I would choose a verse or symbol of my faith that meant something to me, and then get it tattooed.

As I grew older and eventually distanced myself from that evangelical subculture, I began to meet people from similar backgrounds who had Christian tattoos they regretted, or at least had complicated feelings about. They would point to their tattoos and remark that they got them during their “on-fire-for-Jesus phase,” but now find them “cringy” or “cliche.” Some expressed hopes to eventually get their tattoos covered or removed.

I began to suspect this might be a relatively common experience among the growing demographic of Americans who have both loved and left the church. Near the end of college, as I brainstormed ideas for my own tattoo, I joked with family and friends that it felt safer to get a Harry Potter tattoo than a Christian tattoo: “I don’t know for sure whether or not I will always love God, but I do know I will always love Harry Potter.”

“I found it poetic that, much like Jesus, the scars of our bodies could tell the stories of our faith.”

My confidence was shaken in June 2020 when J.K. Rowling, author and creator of the Harry Potter franchise, tweeted a series of transphobic sentiments. In the time since, she has stood by her comments. Longtime fans have expressed a strong sense of disappointment and even betrayal. I started coming across news articles and social media posts of people getting their Harry Potter tattoos covered or removed. They no longer desired to be associated with her or her values; in fact, they found the constant reminders of her work on their bodies to be harmful to themselves and others.

As someone very interested in the growing field of religious and spiritual trauma, I began to wonder if individuals with these experiences find their Christian tattoos triggering, just as Harry Potter fans did theirs. As my own faith has matured and evolved, I sometimes get emotional or uncomfortable when memories of my past religious experiences emerge. What would it be like if I could not escape those reminders? What if they were visible signs on my body for everyone else to see and interpret? What would it be like to look in the mirror at my most naked and vulnerable state and still see markings associated with a community that taught me I was unworthy?

In seminary, I chose to explore this topic for a Theopoetics class project. Theopoetics is a craft and discipline that values the potential for creativity, aesthetics and imagination to enhance theological reflection and inspire social transformation. My project explored tattoos as artistic expressions that reflect an individual’s embodied experiences, values and beliefs. It argued that tattoos, and the stories surrounding them, are a valuable site for theological engagement and pastoral consideration.

I started with an informal Google survey inviting people to share the stories of their Christian tattoos. I received 20 responses, some of which were very moving. I chose four to focus on for my project. I then put together a small collection of theological reflections crafted with the intention to mitigate the harmful effects of tattoo regret and aversion. I found it is possible for faith leaders such as me to help individuals reframe and reimagine the meaning and/or theology surrounding their tattoos so they serve as a truer reflection of who these individuals are and what they believe.

For example, one of my participants had a tattoo of the phrase “more than conquerors” from Romans 8:37. When they got this tattoo, they believed themselves an agent in the cosmic battle between good and evil. They were ready to be a soldier for Christ, yielding his word like a sword. But as they grew up and left the strict Christian bubble they had spent the majority of their life in, they learned the outside world is not in need of conquering — it is in need of compassion.

“There is something empowering about reclaiming your body and your story.”

So what does the phrase “more than conquerors” mean for this person now? It means they are capable of more than just violence. In fact, they are capable of better. They are capable of tending this hurting world with gentle love and grace.

This project taught me there is something empowering about reclaiming your body and your story. The beliefs or sins of others do not have to rob us of meaning or joy. Instead, we get to discover it for ourselves, making changes along the way.

Despite my own struggles with the church, I still find joy in Christian community. And despite J.K. Rowing’s fall from grace, I still find comfort in rereading the Harry Potter series. These experiences have shaped who I am, and it is my responsibility to discern what parts were helpful and which were harmful. What do I take with me, and what do I leave behind?

Perhaps there is an innocence or naivety in the kind of love and devotion we feel so strongly at one point in time that we choose to surrender ourselves over to it completely, believing it must last forever. Maybe there is a level of desperation to it as well. There is something sad yet beautiful about the 18-year-old youth leader whose life feels so out of control that they get the word “peace” tattooed alongside a cross, not realizing the irony in that, and learning only later they would not find peace in church, but in the wilderness, searching the mountains and valleys before finding a true home in the company of others who have been persecuted in the name of Christ, but not by Christ.

These are the parts of ourselves I believe should be embraced, not hidden away. Even if we feel in retrospect that our past selves were too easily deceived or foolish — too quick to trust and believe — there is nothing shameful or embarrassing about admitting the extent to which we once were willing to give ourselves over to a chance at love, faith and belonging.

Life is a constant search for these things. Sometimes we find them in the wrong places, and that is OK. We change and move forward, and our bodies change and move forward with us, telling the stories of where we have been and where we are going.

Madison Boboltz graduated from Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, Texas. There, she studied religion at Logsdon School of Theology. Currently, Madison is attending seminary at Boston University’s School of Theology and is a certified candidate for ordained ministry in the United Methodist Church. She plans to return to central Texas for ordination and begin her career as a pastor.

Related articles:

A tattoo that says, ‘Your story is not over’ | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Don’t panic, mom and dad: your kid’s tattoo may reinforce religious identity