There’s more than the usual political craziness attached to the recent remark by Tennessee Rep. Paul Sherrell to bring back “hanging by a tree” as an amendment to a firing squad bill. There’s a denial of horrible history.

This is the same state representative who recently sponsored a bill to change a portion of Rep. John Lewis Way in downtown Nashville to President Donald Trump Boulevard. The portion of the road he proposed to rename for Trump intersects Dr. Martin L. King Jr. Blvd.

All this screams of racism in its most recent manifestation.

Surely there will be instantaneous denials of racism from those who are oblivious to the power of metaphor encased in the words “hanging by a tree.” But history is a witness.

Rep. Paul Sherrell

Sherrell’s suggestion conjures up a horrific time in American history: the lynching era. In case his historical memory is flawed, here’s the inscription on a postcard depicting the charred remains of Jesse Washington, a lynched black farm worker in Waco, Texas: “This is the barbeque we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe.”

Does Sherrell not know that in the age of lynching, the daily newspapers often whipped up the fury of white masses by invoking the last species of property that all white men held in common — white women?

Does he not have the foggiest notion that the history of lynching must be seen in light of anxiety over the growing independence of women? The breakdown of white male hegemony?

How often do the remedial lessons of Scripture need teaching? “They put him to death by hanging him on a tree” (Acts 10:39).

In the words of Countee Cullen in Christ Recrucified:

The South is crucifying Christ again by all the laws of ancient rote and rule. …

Christ’s awful sin is that he’s dark of hue, the sin for which no blamelessness atones. …

And while he burns, good men, and, women too, shout, battling for his black and brittle bones.”

And as immortalized by Billie Holiday in “Strange Fruit”:

Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

The representative from Tennessee needs a history lesson. Systemic bigotry is still central to our politics; the country is susceptible to such bigotry; salt-of-the-earth Americans whom we lionize in our culture and politics are not so different from those same Americans who grin back at us in lynching photos.

The harder Christian nationalists try to write a revised American history that leaves out the injustice, the oppression, the abuse and the murder of slaves, women, African Americans and gays the more our pathetic legacy keeps shouting from the halls of government, “Hanging by a tree.”

“White Americans who have been shamed by the legacy of racism now are fearless in striking back in the attempt to browbeat and humiliate those who dare to call a racist act the result of racism.”

White Americans who have been shamed by the legacy of racism now are fearless in striking back in the attempt to browbeat and humiliate those who dare to call a racist act the result of racism. Some of these former masters of shame are fighting back in the attempt to repudiate American history, repudiate shame, because it is a helluva lot easier to shout “woke” than to respond to the moral demands placed on them by repentance.

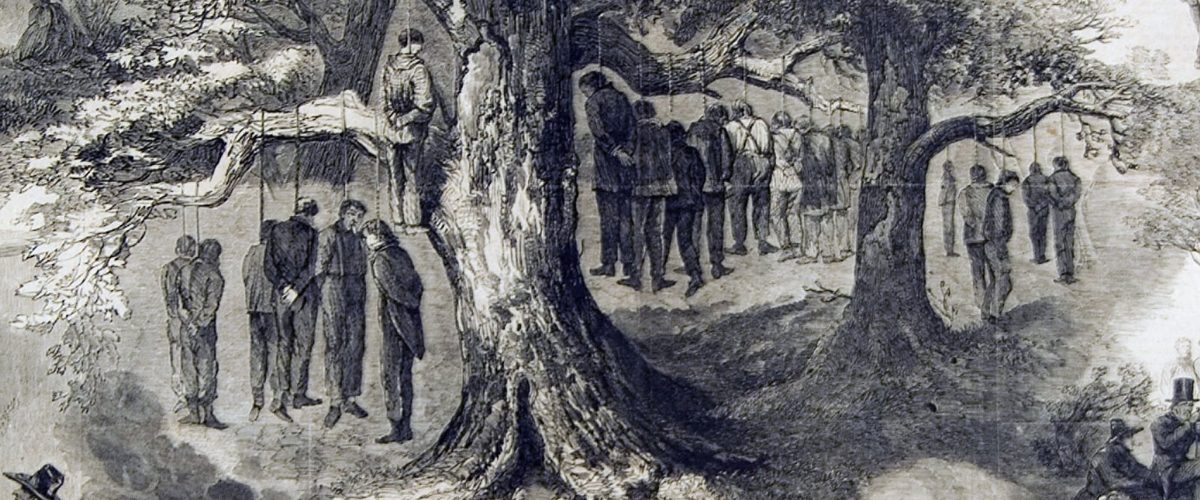

No mention of “hanging by a tree” can be allowed to pass without facing the work of theologian James Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree. Hanging from a tree and lynching are a matched pair in our nation’s history.

Cone forces us to look at the cross and the lynching tree in a composite photo. The image disturbs deeply. As W. Fitzhugh Brundage reminds us, “Perhaps nothing about the history of mob violence in the United States is more surprising than how quickly an understanding of the full horror of lynching has receded from the nation’s collective historical memory.”

But we are required to never forget.

Cone states his case plainly in the introduction to The Cross and the Lynching Tree: “The cross and the lynching tree are separated by nearly 2,000 years. One is the universal symbol of Christian faith; the other is the quintessential symbol of Black oppression in America. Though both are symbols of death, one represents a message of hope and salvation, while the other signifies the negation of that message by white supremacy. Despite the obvious similarities between Jesus’ death on a cross and the death of thousands of Black men and women strung up to die on a lamppost or tree, relatively few people, apart from Black poets, novelists and other reality-seeing artists, have explored the symbolic connections. Yet, I believe this is a challenge we must face. What is at stake is the credibility and promise of the Christian gospel and the hope that we may heal the wounds of racial violence that continue to divide our churches and our society.”

Rep. Sherrill of Tennessee needs to be reminded that “hanging by a tree” is a shameful legacy that has no place in the American lexicon and is no balm in Gilead from the racism that still haunts our nation.

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor in New York state and serves as a preaching instructor at Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump.

Related articles:

Sometimes it’s not a good idea to quote the Bible | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Arkansas panelists describe capital punishment as ‘legalized lynching’