A teacher at a local high school who hadn’t turned 30. A minister who helped baptize my Pap. And just last week my Pap’s brother-in-law Bill, who had the friendliest smile you’d ever seen. Each of them, and many more from Eastern Kentucky, have passed away in the past few weeks, all from COVID-19.

We’re used to wildfires in the mountains, especially this time of year. COVID-19 has spread quicker than any wildfire, blazing its path from one holler to the next, burning through families, churches and communities with no sign of letting up.

Jordan Conley

You might be thinking of a rational explanation of how Eastern Kentucky became ground zero for the Delta variant: “These people voted for Trump, they all believe his lies, and that is why they died.”

These stereotypes have been made for decades, long before the cultural phenomenon of “Trump’s America.” National journalists frequently descend upon Appalachia. While their stories raise awareness of Appalachian issues, they fall short of adequately articulating the context of mountain struggles and tend to draw broad conclusions.

“Poor people don’t know any better” might sell, especially when paired with images of grieving families in front of a fresh mountainside grave, but the challenges that Appalachian people face are far more complex.

Eastern Kentucky and Central Appalachia have experienced monumental health care challenges for years. For most Eastern Kentuckians, local hospitals are a half hour to an hour’s drive away over narrow mountain roads. When I was growing up, hearing that someone had been “flown out” to hospitals two hours away in Lexington, Ky., Huntington, W.Va., or Johnson City, Tenn., was a sure sign that they were fighting for their life.

Statistics show that in Eastern Kentucky, infant mortality rates are higher while life expectancy rates are lower. Heart disease, lung disease and diabetes are all common, and cancer rates are astronomically high, leading Eastern Kentucky to be called “the cancer capital of America.”

The people of Eastern Kentucky have experienced economic exploitation for generations. Out-of-town coal operators made billions off coal, taking “mineral rights” away from unsuspecting home owners through “broad form deeds” that separated a property owner’s “surface” rights from “mineral” rights, meaning most homeowners never had a say in whether a mine could operate underneath their home. Today, coal boom towns function as modern-day ghost towns, with absentee landlords owning the majority of property in counties that struggle to provide minimal community services, in part because of a lack of revenue from property taxes.

“The people of Eastern Kentucky have experienced economic exploitation for generations.”

This was part of the fuel that sparked the COVID-19 wildfire. Most churches haven’t helped the response to the pandemic. Facebook posts read, “If you can go to Walmart, then you can go to church.” One Eastern Kentucky pastor recently invoked the persecution of first century Christians to compel church attendance during the pandemic. If Paul and others “went to church” knowing they could die at the hands of the Roman Empire, then today’s Christians shouldn’t be afraid of going “because of COVID.”

Faith is about the only hope mountain people have had to look to over the years. The mining industry always has been “boom or bust,” a promise of a new road project or factory bringing jobs always is in the news, but it almost never materializes. Through the trials and tribulations of life in the mountains, folk through the generations have gone to church, singing hymns like, “I can’t feel at home in this world anymore.”

Mainline Protestant churches talk a lot about caring for the poor, and some back up that talk with action. However, progressive Christians and theologies of liberation that seek to uplift the oppressed almost never mention Appalachians. Mountain folks are broadly categorized as “working-class, rural, white people” — in other words for many progressives, “the enemy.”

“How many more pandemics will it take before the church calls for a new, just Appalachia?”

Liberation theology has been a gospel of hope for the oppressed. Appalachia has been a stomping ground for the “principalities and powers” for hundreds of years. How many more pandemics will it take before the church calls for a new, just Appalachia?

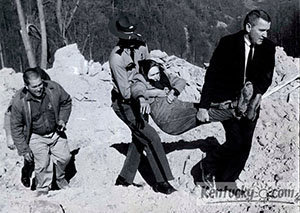

Eula Hall (AP Photo/Ed Reinke)

Mountain folk have been imagining such a world for a while.

Folks like Eula Hall, an Appalachian woman who saw a need for poor people to have a way to seek health care and mobilized her community to build a clinic in the head of a holler.

The widow Ollie Combs being forcibly removed from protesting a coal mining project.

Folks like Ollie Combs, who sat in front of a bulldozer to stop the strip mining of the ridge above her home.

These women became agents of liberation in Appalachia through refusing to back down in the face of injustice.

The Delta variant is raging in Eastern Kentucky, and it is raging because of systematic failures of a society built upon injustice, a society of oppression that values profits over people.

The Scriptures invite us to “act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with God.” If the church is brave enough to have eyes to see, it will see a people who have suffered unjustly for too long.

It is time for the church to see Jesus as a coal miner, struggling to carry the heavy cross up Golgotha’s hill as the coal dust clings to his lungs. It is time that the church join with Appalachians seeking to be agents of change in the mountains. It is time that the church walk in the footsteps of the oppressed in Appalachia, even to the head of the holler.

Jordan Conley hails from Eastern Kentucky and now lives in Louisville, where he recently was called as interim minister to youth and young adults at Crescent Hill Baptist Church. He is a student at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky and is currently serving an internship with the Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists.

Related articles:

Southeast Kentucky: Enduring images

Nationwide, twice as many people are hungry during pandemic

Hope for a new year out of the historical disunity of our United States | Opinion by David Jordan