Last month at the American Cathedral in Paris, where I serve as canon theologian, I gave a talk on my journey from “quirky American theologian” (as the UK’s Greenbelt Festival advertised me when they invited me to give talks on faith in Harry Potter and in stories of the Zombie Apocalypse in 2017) to hardcore advocate for racial justice.

That shift has taken place over the pandemic, when I released a book on race, film and faith for Oxford University Press— and when white pastors, priests and Episcopal bishops began reaching out to me to talk with mostly white congregations who, after George Floyd’s murder, wanted to lean into the work of racial healing.

‘Why are you doing this?’

This talk was prompted by an interview I shot with Fox News on Critical Race Theory, book censorship, faith and patriotism. It was less adversarial than I’d expected, but it ended with a question I have heard a lot in the past two years: “Why are you doing this?”

“Maybe you haven’t looked in the mirror lately, but you, sir, are white. Aren’t you getting out of your lane?”

Which usually means, “Maybe you haven’t looked in the mirror lately, but you, sir, are white. Aren’t you getting out of your lane? Why on earth should you be talking about race and prejudice?”

Well, there are reasons.

Greg Garrett

In Paris, I started speaking as I typically do, with my history: In recently desegregated elementary schools in Georgia and North Carolina in the 1960s, I saw beloved classmates mistreated based on the color of their skin. Kids have an inherent eye for injustice, and I’ve never forgotten that deep early awareness of unfairness.

As an adult, in my darkest hours, I was rescued by St. James Episcopal Church, a historically African American church in East Austin. Although the original members had been despised and rejected, these good Christians manifested the absolute welcome and love of God to me. Their courage, their faithfulness, changed and challenged me to live further into a vision of faith linked to God’s justice.

In recent years, my life and work have been shaped by friendship and collaboration with scholars, theologians and clergy of color. A colleague at Washington National Cathedral told me a while back that she has seen me grow by leaps and bounds as I’ve convened and participated in conversations about racism, culture, justice and faith. I hope so. I will say: I’m still learning, still growing, and am more and more convinced that this work matters.

“I’m still learning, still growing, and am more and more convinced that this work matters.”

Which is not to say it is easy.

This is a problem created by white people

Even before I began my last book, I understood white people don’t really want to talk about racism. Racism is either not a problem any more (Obama, remember?), or not my problem (“I’m not a racist”).

Meanwhile, I had discovered that many people of color have grown frustrated by being asked to educate white folks about their lifelong struggles against racism and within a racist system, and they’re exhausted by how things don’t seem to change. They’re heartbroken. I remember a Black leader in the Episcopal Church asking on social media after yet another questionable police shooting: “When y’all gonna stop killing us?”

I comprehend that frustration, that exhaustion, that heartbreak, and I never have had to inhabit those spaces, let alone spend my whole life wrestling with these questions.

What I told the reporter from Fox, my audience in Paris, and you, is that, yes, I have checked the mirror. I am white, so it might seem I’m not personally affected by racism. That it isn’t my problem. But I am. And it is.

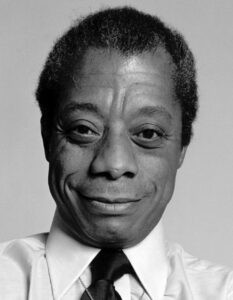

James Baldwin

James Baldwin often said we white people are enslaved by our bigotry, our inability to acknowledge our history, that none of us in America can rise except by throwing off our chains together. And Catherine Meeks has told me that all Americans — “including you, Greg” — suffer from racialized trauma. Our history damages each of us.

I also said and say that I feel called to write, teach and preach about racism because people with power have a responsibility to work on behalf of all those who are exhausted and ignored, all those who are marginalized, and people like me are called to do so because we need to effect change, not simply call ourselves allies marching alongside people of color.

During the pandemic, my friend the great Black theologian Kelly Brown Douglas schooled me: “When one speaks of allies, it is as if the allies are helping you to solve a problem that is yours and not theirs. The fact of the matter is that white racism is white people’s sin. I didn’t create this problem, Greg. You did.”

“The fact of the matter is that white racism is white people’s sin. I didn’t create this problem, Greg. You did.”

If this is true — and I have to believe it is — then only me and people who look like me ultimately can overturn it.

So no, I don’t own slaves, nor did my ancestors. No, I never would shoot a Black jogger, or shout racial epithets. But that doesn’t mean that I — or you — can declare racism over and the work of reconciliation complete, although we might like to. No, far from it.

Addressing the enormous divides

Wrestling with individual racism is only a beginning. The longer game has to be addressing the enormous divides between the richest and poorest, the ones who live and the ones who die, baked into American life largely based on the color of our skin.

And the biggest problem, as Baldwin put in in his late-life essay No Name in the Street, is that the richest and most powerful of us don’t want to know about these divides because that awareness would overturn our comfortable lives: “It is not even remotely possible for the excluded to become the included, for this inclusion means, precisely, the end of the status quo.”

We, the powerful can’t, or won’t, open our eyes and realize the price paid by the marginalized. And so we can only conclude that when the victims stand up and speak out — saying, for example, that Black Lives Matter — then the “barbarians” are in rebellion against white civilization.

But recent weeks have made it only increasingly clear that a civilization that centers white Christian men is going to be oppressive for almost everyone else: for women, for LGBTQ folks, for immigrants, for Black and indigenous people and others of color, for the working poor, for people from other faith traditions and none, for everyone who doesn’t already reside atop the ladder.

The people of God need to remember that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. And white people — especially white Christian men — need to be at work, on the frontlines, seeking to overthrow the injustices that have soiled this nation for 400 years, and will continue to do so unless all of us are willing to rise up against our status quo and stand for God’s justice.

Greg Garrett is Carole McDaniel Hanks Professor of Literature and Culture at Baylor University and canon theologian for The American Cathedral in Paris. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of more than two dozen books, most recently In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is currently administering a research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and writing a book on racial mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and canon theologian at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Three things white Christians can do to address white supremacy: Lament, repent, dissent | Opinion by Joel Bowman Sr.

Now is the time when we need to hear white evangelical leaders refute white supremacy | Opinion by Joel Bowman Sr.