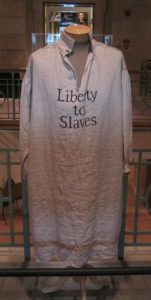

“Liberty to Slaves.” Those were the words that were emblazoned on their uniforms as they went into battle as members of the Ethiopian Regiment. The regiment had gathered in response to the proclamation issued by Lord John, the Earl of Dunmore, on Tuesday, Nov. 7, 1775.

Lord Dunmore was serving at the time as the British colonial governor of Virginia, and his proclamation declared that “all indentured Servants and Negroes” would be freed if they were “able and willing to bear Arms” in support of “his Majesty’s Troops.” The proclamation ended with the simple and unforgettable words, “God Save the King.”

The historical records available suggest that slaves from Georgia to New York, New Jersey and the colonies of New England responded to the proclamation and made the decision that if white men were going to fight for their freedom from Britain, then they (as Black men) were going to fight for their freedom from bondage.

While the men of that regiment were subject to second-class status as soldiers and relegated far too often to foraging and manual labor, they did see battle on at least one occasion during the year 1776, the one year they were in service. Sadly, hundreds of them succumbed to a smallpox outbreak, and Lord Dunmore ultimately retreated to Great Britain as it became clear that the Loyalist cause was lost.

“The story of the Ethiopian Regiment matters because if we are being honest, it is the first known ’emancipation proclamation’ ever issued to slaves held on American soil.”

Some of the surviving Black soldiers returned to England with Dunmore, and thousands more (both directly connected to his regiment and otherwise) were evacuated to Nova Scotia before the War for White Male American Independence concluded.

The story of the Ethiopian Regiment matters because if we are being honest, it is the first known “emancipation proclamation” ever issued to slaves held on American soil, nearly a century before President Lincoln’s famous executive order. But it also is important because it is part of the forgotten history of the African American experience that has been “forgotten” intentionally, because it does not align with the melting pot mythology and the “land of opportunity” narrative that has been violently enforced in this nation since its inception.

That mythology has been shattered, and that narrative has been jettisoned in recent months with a ferocity that few could have anticipated, even though the work of “complicating” this myth/narrative has been underway for at least 50 years. As I shared with my congregation last Sunday, if I had been living on colonial American land in 1776, I would have made every effort to join the Ethiopian Regiment, and I would dare anyone to call me a traitor for saying so.

One of the most important exercises going on right now is the “uncomfortable conversations” that are pointing out the total disparity between the experience of privileged whites who have run this nation since they declared their independence, and the rest of us (who have existed on the underside of that history, struggling to survive, and — in our better seasons — even thrive in spite of constant oppression). Those conversations require us to steadily dig up these stories that have been brushed aside and place them front-and-center as a means of fundamentally shifting the narrative and rewriting the myth in order to be more transparent, honest and, ultimately, real.

“These intentionally forgotten stories bring us to grips with the moral bankruptcy that pierced the heart of America’s framing spirit.”

These intentionally forgotten stories bring us to grips with the moral bankruptcy that pierced the heart of America’s framing spirit. That moral bankruptcy has broken us, in ways that every Black abolitionist from David Walker to Frederick Douglas to Henry Highland Garnet understood in biblical terms.

Long, long before Martin Luther King Jr., ever planned to preach “Why America May Go to Hell,” (which was the title of the sermon he would have preached on April 7, 1968, at Ebenezer Baptist Church), these men recognized and declared that the United States was damned because of its moral bankruptcy.

They were right, and that damnation has been expressed in the civil unrest, wars and urban/suburban rebellions that have raged across this nation since its founding. The work of this present season must be understood and engaged as the work of repentance, redemption and restoration. Only then will any American politician or public leader ever be justified in referring to this country as being “great.”

Scripture suggests that this redemptive/restorative project is not out of reach, even if it will require us to stretch ourselves further than the white and the privileged have ever been willing to go. The prophet Isaiah declares to a people who were experiencing a similar season of moral reckoning that God will “come to Zion as a Redeemer, to those in Jacob who turn from transgression.” He promises further that God will put the divine spirit in their mouths, and that this spirit will “not depart out of your mouth, or out of the mouths of your children, or out of the mouths of your children’s children … from now on and forever” (Isaiah 59:20-21).

What does that means for us if we can just lean in to this anti-racist, sacred work long enough for our children and our children’s children to take it into their hearts, build it like a monument in their minds, and sanctify it like communion in their spirits? If we can do that just long enough to reach two generations of our people, then God will redeem and restore us to the “city on a hill” that white male colonists once aspired to be.

That’s my prayer, but it will also be our work for the years to come.