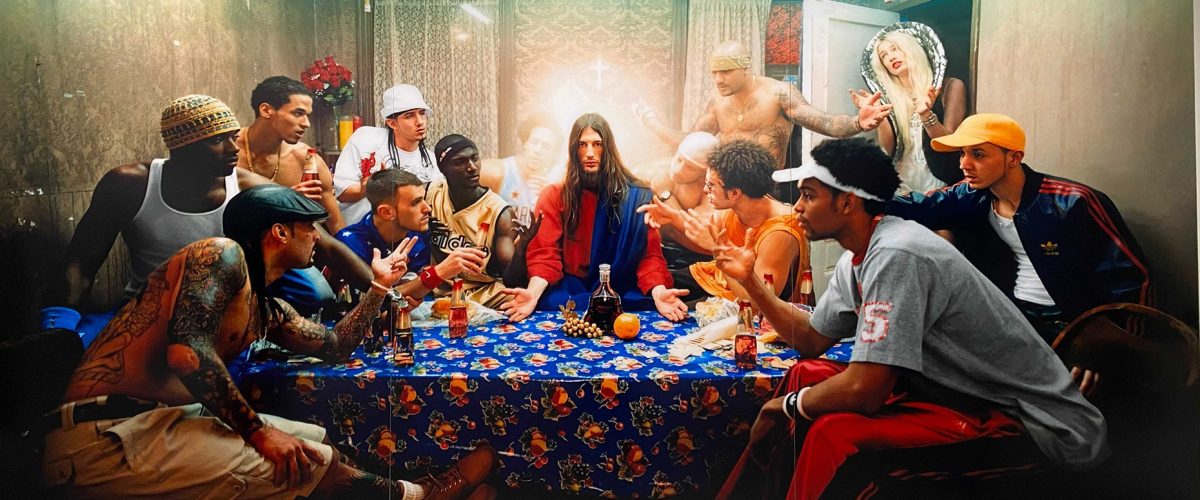

A hybrid God

An 82-year-old man is attacked by a hammer-wielding fanatic and political celebrities snicker and sneer. Nancy Pelosi has been demonized by the conservative movement so viciously, and for so long, that hyper-partisans like Donald Trump Jr., Kari Lake, Charlie Kirk and Steve Bannon use the attack on Paul Pelosi as more grist for the political mill.

In 2015, we were shocked by the white evangelical embrace of a debauched conman. Perhaps, we surmised, the pious folk were simply holding their noses in hopes that Donald Trump would champion their core issues. There was some persuasive power in that explanation. But it was soon obvious that millions of white evangelicals were invigorated, even thrilled, by Trump’s enemy-eviscerating rhetoric.

Alan Bean

How could this be? Didn’t white American evangelicals celebrate “the biblical worldview”? And doesn’t the Bible teach us to bless, pray for and forgive our enemies?

Yes and no. Psalm 103 insists that “the Lord is good to all, and his compassion is over all that he has made.” We are assured that God is well-versed in our foibles and failings. “For he knows how we were made; he remembers that we are dust.”

On the other hand, consider the first few verses of Nahum: “A jealous and avenging God is the Lord, the Lord is avenging and wrathful; the Lord takes vengeance on his adversaries and rages against his enemies.”

“In the final draft of our theology, God’s friends receive compassion while God’s enemies reckon with wrath.”

Incorporate these passages into a “biblical worldview” and God comes off as a volatile mix of wrath and compassion. In the final draft of our theology, God’s friends receive compassion while God’s enemies reckon with wrath.

Jesus and the God of universal compassion

Jesus rejected this hybrid deity. “You have heard it said,” he told the multitudes, “‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven.”

Compassion must be unqualified, Jesus says, because the compassion of God is boundless. God is limitless compassion.

This teaching proved controversial. Since some people are clearly more deserving of divine mercy than others, universal compassion seems inherently unfair. Many of the parables Jesus unleashed into the world address this complaint. Those who labor in the vineyard from dawn until dusk receive the same wage as those who show up at closing time. The Prodigal Son is forgiven, even celebrated, while the faithfulness of his fastidious brother feels ignored.

Universal compassion was the lifeblood of the heavenly-earthly kingdom Jesus proclaimed. God’s wrath, Jesus says, falls upon child abusers, those who refuse to help prisoners, the enslaved, widows and landless sojourners. The parable of the sheep and the goats, like the story of Lazarus and Dives, describe the fate of those who withhold compassion.

Why the church qualified compassion

There are innumerable reasons why universal compassion was shunted to the sidelines, but I will mention just three.

First, it didn’t preach. A message “preaches” when it sends ripples of excitement through an audience. Universal compassion doesn’t do that. A message centered in condemnation and promises of divine vengeance does.

Second, it produced anxiety. We inhabit a world brimming with dangerous people who wish us ill. We need sword-wielding allies like Emperor Constantine or, in our day, Donald Trump.

Third, the expansion of Christianity almost always has been preceded by military conquest. Militant expressions of Christianity suited the context; universal compassion (to put it mildly) did not.

“As a general rule, the clear teaching of Jesus has suffered the death of a thousand qualifications.”

The radical love of Jesus always has been an ingredient in the Christian stew. The doctrine of universal compassion has exercised a leavening influence in every branch of the church in every epoch. The concept is too tied to Jesus to be utterly extinguished; but it always has operated at the margins. As a general rule, the clear teaching of Jesus has suffered the death of a thousand qualifications.

Theological objections to universal salvation

First, universal compassion leads logically to a belief in universal salvation. We’ve always preferred an end-times scenario in which we are rewarded with heaven while they can just go to hell. However, if “every tongue shall confess that Jesus Christ is Lord,” we must reckon with a radically depopulated hell.

Second, doesn’t universal compassion eliminate the very biblical concept of divine vengeance?

Third, talk of universal compassion frustrates the biblical passion for justice.

The best response to these objections is provided by the “burning coals” passage in Romans 12: “Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.’ No, ‘if your enemies are hungry, feed them; if they are thirsty, give them something to drink; for by doing this you will heap burning coals on their heads.’”

The vengeance of God is a product of radical forgiveness. The oppressed of the world receive compassion as a healing balm. Oppressors experience unmerited grace as an insult, as divine vengeance.

“Powerful people have little use for the suite of virtues we call compassion, mercy, grace and forgiveness.”

Powerful people have little use for the suite of virtues we call compassion, mercy, grace and forgiveness. They may dispense these gifts, like a prince tossing farthings to the rabble; but they are never the recipients. Compassion turns the tables, and it stings like fire.

Followers of Jesus can’t be culture warriors

We can’t accept the core message of Jesus without rethinking Christian theology and church history from the ground up. Our house of faith must be stripped to the rafters. We may even discover some of the rafters must be discarded. We must unstop our ears and open our eyes to radical ideas. The church militant must give way to the church penitent.

Following Jesus requires the abandonment of the warrior mind. The moral and political debates of our day hinge on the embrace or rejection of radical compassion. Culture warriors, regardless of ideology, long for the defeat, indeed the annihilation, of the opposing camp.

In an America rapidly splitting into two armed camps, each working for the obliteration of the other, genuine Christian piety is hard to find, or even fathom.

“Conservative culture warriors have declared war on universal compassion.”

Conservative culture warriors have declared war on universal compassion. They view it as sin. Their political strategy is predicated on picking fights and hooking outrage. The strategy is to stoke fear of the other: immigrants, people of color, feminists, the LGBTQ community, non-Christians, atheists, agnostics, and, of course, mainstream purveyors of information and entertainment. Compassion has become a dirty word associated with weakness and complicit in failure.

Recoiling in horror, progressive culture warriors cast nightmare visions of what America under Christian nationalism, theocracy, misogynistic patriarchy and fascist autocracy would look like.

In both cases, the political struggle (secular and ecclesiastical) is conceived as a zero-sum, winner-take-all brawl. If the other side survives, we are told, America is doomed.

Only Jesus can save us

Those willing to study war no more can’t guarantee the enemy will follow suit. Spiritual disarmament is almost always unilateral. This is true for conservatives, progressives and for those who feel alienated from both ends of the ideological spectrum.

But the way of compassion never has been easy. In fact, it’s impossible. I never have been able to pull it off, and I doubt you have either. I am charmed by the big idea Jesus bequeathed to the world until Rachel Maddow reports Marjorie Taylor Greene’s latest outrage. Then all bets are off.

We are hardwired for vengeance; that’s why revenge films are so popular. Compassion comes naturally when we see a newborn baby, or when a close friend is diagnosed with cancer. But ask us to love and forgive people we perceive as an existential threat, and we seek more promising remedies.

And yet, my failed attempts to love and forgive everyone for everything have been transformative failures. Simply trying makes me a better person.

Communities of compassion

Cruelty is a team sport. We feed on the rage of the tribe. Blessedly, community also can work as a compassion enhancer. When our sermons, our hymnody, our prayers and our public witness reflect the radical love and forgiveness of Jesus, miracles break loose. The first generations of the Christian movement understood this. Then the core teaching of Jesus was shoved to the margins and its wonder-working power was squandered.

If we are willing to believe Jesus; if we are willing to undertake a ruthless re-examination of our tangled history and compromised theology; if we are willing to renounce partisan hatred; and if we are willing to center our worship and mission in the universal compassion of Jesus, tongues of fire will dance again.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

A rebirth of compassion? | Opinion by Bill Leonard