Taking a look at our world today, we find that while the profile of Asian Americans may rise in the popular American imagination, the Asian American woman is still shrouded in obscurations created by the white dominant society. The visible and invisible in society are reflected throughout Scripture as a major biblical theme.

Sociologically, most women have been invisible throughout history, but Asian American women’s invisibility contrasts with the growing prominence of white feminists — white women who are often aligned with the model minority Asian American women. Invisibility may mean powerlessness, voicelessness, marginality and an inability to put forward unique issues. Therefore, it is important to reimagine the dominant theology into a fully progressive, inclusive and intersectional praxis that can lead to the awareness, understanding and acceptance of our Asian neighbors and prevent the silencing of the voices of Asian American women.

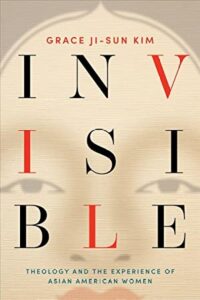

Grace Ji-Sun Kim

Understanding how Jesus sought to counter biblical women’s invisibility helps us better practice a theology of visibility that empowers Asian American women. We see it in stories about foreign women, lepers, the Samaritan woman and Mary Magdalene.

No-name women in the Bible

The roles of women in the Bible are believed to have been not presented in full or omitted entirely during and after the Bible was written. Even when women are present in the stories, their names usually are not given. We have the woman who anointed Jesus’ feet (Luke 7:36–50), Lot’s wife (Gen 19:15–26), Jephthah’s daughter (Judges 11), the woman caught in adultery (John 8:1–11), the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4:4–26), the poor yet generous widow (Luke 21:1–4), the Canaanite woman (Matt 15:21–28), and the bleeding woman (Matt 9:20–22). The exclusion of these women’s names marginalizes them and further makes them invisible.

The stories of no-name women in the Bible provide some insight into why women were made invisible during biblical times as well as throughout much of church history. Asian American women are seen as a moral threat, defined by the image of being a subservient, hypersexualized lure to white men. Therefore, dominant society created the Asian American as invisible, silent and unnamed.

In Luke’s Gospel, the story of the sinful woman shows how patriarchy attempts to erase women’s presence, while God intends to lift women up (Luke 7:36–50). Sin for biblical women often was associated with sex, leading some to infer that the women were prostitutes. In this story, an anonymous woman comes into the Pharisee’s house and anoints Jesus. The no-name woman learns that Jesus is eating at the Pharisee’s house, so she enters with an expensive alabaster jar of perfume. She stands behind Jesus, weeping, and her tears began to wet Jesus’ feet. She then wipes his feet with her hair, kisses them and pours perfume on them. Jesus creates a lesson of love and forgiveness from this event. It becomes an important lesson, as it exemplifies Jesus’s incarnation, ministry, crucifixion and resurrection.

“Only her ‘sinful’ character is remembered and written in the Scriptures regarding her identity.”

However, the woman’s identity and name are not given. Only her “sinful” character is remembered and written in the Scriptures regarding her identity. The male biblical writer wanted to emphasize that the woman was probably a prostitute. The way this story is written reveals how patriarchy tries to highlight the sin of women and not patriarchy, which oftentimes forces vulnerable young women to become sex slaves or prostitutes. Patriarchal writers eliminate women from historical events, as women’s names were less important in society. Women are viewed in relation to men, as this woman is described as “sinful” in the sense that her sin is tied to her sexuality. Despite the beauty of the symbolic preparation for the upcoming burial of Jesus, this event will forever be tied to her sexual “sin.”

When God created the world, God made men and women equally. Men and women were intended to be the exemplars of creation, loving and caring for the other, not dominating the other. Creation was beautiful, and everything in it was good. We must not continuously portray women as evil; they are good, essential, valuable and chosen by God. Though the biblical women discussed here are remembered despite their ambiguity, they have no names and no faces — they are invisible.

The costs of invisibility

What happens to the invisible? Not only are they not seen by the dominant society, but their voices are also drowned out or ignored. The loss of Asian American women’s individual and communal voice is a detriment to society, as their voices can fuel social and cultural change.

When I think about my own Asian heritage, I see that many Asian American voices are pushed to the margins and made invisible. Their cries of racism, discrimination and stereotyping get muffled through the “model minority myth” or the bestowing of the title “honorary whites.” These terms are used to downplay Asian Americans’ suffering. Because of this forced invisibility, Asian Americans lack social, political and cultural power. Therefore, embracing a theology of visibility will take us one step closer to eliminating the evils of racism, discrimination, sexism and xenophobia that continue to oppress Asian American women.

Asian American women contributing to a theology of visibility

The voices of Asian American women are powerful. They add the richness of Asian philosophy, religion and culture. They add a new, liberative dimension to a white heteronormative theology by integrating Asian heritage, practices and beliefs.

As Asian American women work toward a theology of visibility, they should seek to empower other oppressed, invisible groups.”

Asian American women have the power to diversify the human spectrum of Christian identities and uplift the voices of all other marginalized women. As Asian American women work toward a theology of visibility, they should seek to empower other oppressed, invisible groups to move beyond their experiences of discrimination and claim their space in the kin-dom of God.

My Asian identity has greatly informed my understanding of God and visibility within my spiritual journey. There are four Korean concepts that shed light on how the Holy Spirit improvises a praxis of visibility. These four elements help Asian American women live in a theology of visibility that draws them away from the shadowed fringes, brings the invisible others out into the light, and embraces them all in the center.

Those who practice a theology of visibility should feel enriched and blessed with the education that heritage provides. Asian Americans are endowed with complex culture, abundant in ideas and concepts that challenge and complement those from the West.

The deep, collective sense of the Asian experience comes from the concept of ouri, meaning “our,” as well as the concepts of han, which can be translated as “unjust suffering”; jeong, which means “sticky love”; and Chi, an Asian concept that signifies the spirit. These concepts help define Asian society by organizing the collective sense of self and shared group identity, which contradict the ideals of Western society.

For Asian American women to become visible as full participants in the kin-dom of God, theology must embrace these Asian concepts and make them part of the theological conversation. In many ways, this discussion recaptures the remarkable boundary crossing that characterized the early church.

Grace Ji-Sun Kim is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind., and earned a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. She is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the author or editor of 20 books. This article is excerpted from Invisible: Theology and the Experience of Asian American Women by Grace Ji-Sun Kim copyright © 2021 Fortress Press. Reproduced by permission.

Grace Ji-Sun Kim is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind., and earned a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. She is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the author or editor of 20 books. This article is excerpted from Invisible: Theology and the Experience of Asian American Women by Grace Ji-Sun Kim copyright © 2021 Fortress Press. Reproduced by permission.

Related articles:

I knew the truth about women in the Bible, and I stayed silent | Opinion by Beth Allison Barr

Fox News anchor gives voice to 16 women in the Bible

Is a woman in that story? | Opinion by Laurel Cluthe