I confess to the temptation of dismissing evangelical rhetoric of the political sort as symptomatic of one or another particularly noxious pathology. There’s also my own impatience at what I discern as the absurdity of evangelical political messages confidently delivered by persons who seem to have made no discernible effort to ascertain the contestability, the nuances, the ambiguities, the partial truth, and majority lies that are contained in their utterances.

The tribe of evangelical preachers seem to share an imagination that Christianity, in its birth, was as certain, as evangelical, as political as they are now. The perorations and tirades of these “court evangelicals” as they gravely and condescendingly inform me that I have taken leave of my senses and that my deepest theological convictions are irrational, that the God I worship is the product of my elitist imagination, and that I need to repent at last of my pagan, demonic, savage credulity.

Rodney Kennedy

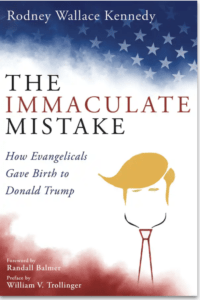

I don’t, however, accuse them of hypocrisy or self-righteousness. Nor do I think them easily duped or lacking in sincerity. They are very serious believers. Like Roderick Hart, in his work, Trump and Us: What He Says and Why People Listen, I believe evangelicals are worthy of being considered politically, rhetorically and theologically. There have been compelling and intelligent answers to the question of how evangelicals and Trump got together — written by academics, journalists and cultural commentators. My perspective is that the evangelicals, after decades in the laboratory of another world, a safe world they created to nourish, develop and maintain their view of the world, managed to give birth to a prodigy of their own making, Donald J. Trump.

Donald Trump is exactly the president evangelicals wanted. Trump is not only attached to the evangelicals; the two have become one body. This is about fear, anger and resentment. It’s about politics and theology, but mostly it’s about pragmatic evangelicals who wish to control what Yoder called “the handles of history.”

This is about winning, the take-no-prisoners, bare-knuckled, no-holds-barred kind of winning. This is the story of the lines of connection, the merging of styles, the similarities in the rhetoric, the smooth alliance of two entities of wealth and celebrity, and the potential destructive tendencies of this aligning of the stars.

This is not a shotgun wedding, but it is a marriage that has produced a political offspring, and since it involves a deeply moral and righteous people, the evangelicals, it bears the title of The Immaculate Mistake: How Evangelicals Gave Birth to Donald Trump. This is an artificial insemination at least a century old in producing an offspring: a tough, resentful man; a messiah anointed by the conservative evangelicals; a man whose gospel centers on getting even; a strong man to stand up to the perfidious liberals.

“This is not a shotgun wedding, but it is a marriage that has produced a political offspring.”

This is not an attempt to prove a hypothesis or to suggest that an absolute causal relationship has been established. I suggest that the evidence points in the direction of Trump being the offspring of evangelical conservatives, who in becoming more and more secular, have at long last produced a political prodigy who thinks and acts like them, but is not hindered by any religious scruples. Instead of being a collection of dummies, the evangelicals are the organ grinders; Trump is their monkey. The divisive, often offensive, over-the-top, blustery, rhetoric of the preachers provided the seed that issues in the speeches and tweets of Donald Trump.

Evangelical preaching lives in a crystal sea of certainty. There is no suggestion or hint of probability, only the definite “this is the way it is.” Flannery O’Connor, in The Habit of Being, says, “The mind serves best when it’s anchored in the Word of God. There is no danger then of becoming an intellectual without integrity.” This would be helpful to evangelicals if they were so anchored, but in reality, they are only anchored in the black leather cover of the Bible — a symbol of literalism unrelated to the actual canon.

Billy Graham habitually intoned, “The Bible says.” Donald Trump often says, “Believe me.” The words “God told me” are prominent in this kind of preaching. This language is a powerful persuader for a people trained to think of the Bible as literal truth and the pastor as the keeper of that literal truth.

Billy Graham habitually intoned, “The Bible says.” Donald Trump often says, “Believe me.” The words “God told me” are prominent in this kind of preaching. This language is a powerful persuader for a people trained to think of the Bible as literal truth and the pastor as the keeper of that literal truth.

Robert S. McElvaine, in The Great Depression, says, “In the reckoning of Believers, ‘in fact,’ is a phrase as weightless as an astronaut in space. Evidence that goes against received Truth thereby proves itself to be false. True believers prefer saying ‘the evidence be damned’ to being damned by the evidence. There are no hypotheses for people of faith. Blind faith would not be blind if it could see facts.”

“Buried within the evangelical conviction that this is a war there’s the psychology of treating the enemy as less than human.”

In the minds of evangelicals, they are a tribe besieged by an encroaching secular, liberal enemy. They feel trapped, discounted and demeaned. Perhaps they suffer from forms of post-traumatic shock that comes from engaging in at least 100 years of war with modernists and liberals. Buried within the evangelical conviction that this is a war there’s the psychology of treating the enemy as less than human.

Donald Trump visits St. John’s Episcopal Church for a now infamous photo opportunity.

For example, participants in Trump rallies project Democrats as pedophiles, as agents of sex slavery, as murderers. Jeff Charlet, in an extended interview with a Trump supporter at one of these rallies, is told that the Clintons are killers. The term the Trump supporter uses is “Arkan-cide.”

David Livingston Smith chronicles the processes by which we reduce fellow human beings to being animals, demons, enemies. Nowhere does this tendency manifest itself as in war. The propaganda of warring countries concentrates on depicting the enemy as a bunch of animals, fit only to be killed. “The great chain of being,” Smith says, “continues to cast a long shadow over our contemporary worldview. It’s also a prerequisite for the notion of dehumanization, for the very notion of subhumanity — of being less than human — depends on it.”

Donald Trump is part revivalist Billy Sunday, part antagonist J. Frank Norris, part televangelist Jerry Falwell Sr., and part prosperity gospel preacher. If Billy Sunday is religious vaudeville; J. Frank Norris, Barnum and Bailey’s Circus; and Falwell Sr., the televangelist; Donald Trump is the secular revivalist/televangelist. He is the culmination of evangelical faith, minus the faith. He combines revival rhetoric with declension messages; he demonizes a large array of enemies with a dogged certainty that would have made Sunday proud. He combines wealth and Christianity. Donald Trump is the most famous secular evangelist in the world. I confess to disliking Trump as much as every hellfire and damnation evangelist that disrupted the dreams of my childhood.

“Donald Trump is part revivalist Billy Sunday, part antagonist J. Frank Norris, part televangelist Jerry Falwell Sr., and part prosperity gospel preacher.”

When Trump somehow won the presidency, a group of evangelicals gathered in a New York ballroom were shouting and some were crying. “It was as if God had answered our prayers and the impossible had happened,” said Steve Strang of Charisma magazine.

Strang is the pioneer founder and CEO of Charisma Media and was voted by Time magazine as one of the 25 most influential evangelicals in America. He’s been featured on Fox News, CNN, MSNBC, CBN, James Dobson’s “Family Talk” and many Christian outlets. Steve’s latest book is titled God, Trump and the 2020 Election, and he claimed, “We had a new president: an outsider we believed God had raised up to shake the United States out of its comfortable slide toward globalism.”

It was reminiscent of Eisenhower seeing his win as a national mandate for a revival: “I think one of the reasons I was elected was to help lead this country spiritually,” he said. “We need a spiritual renewal.”

Conservative evangelicals celebrated coming in out of the cold, coming home from intellectual exile, political defeat and decades of injurious accusations of being a bunch of dummies. They now felt not only their usual righteousness, but good. Never discount the power of “feeling good” when it comes to evangelicals.

Trump tapped into the insatiable desire of evangelicals to “feel good” rather than shamed by the civic morality of gay rights and immigrant rights and abortion rights.

Donald Schaefer argues that “feeling good” is the product Trump sells his followers. Schaefer offers a visual metaphor that I find illuminative of evangelical leaders: Pepe the Frog, a human-bodied frog character created in 2005 by cartoonist Matt Furie. Pepe, “unflappable when confronted, waves off all embarrassment with a stoner smile and a breezy” catchphrase, “Feels good man.” Shaefer says, “Pepe’s smug but goofy hangdog routine evolved into the perfect emblem for (evangelical’s) approach to politics — a refusal to be shamed. Pepe’s shtick is to deflect every attack with a shrug. His grinning defiance of every effort to shame him became theirs.”

Rodney W. Kennedy currently serves as interim pastor of Emmanuel Freiden Federated Church in Schenectady, N.Y., and as preaching instructor Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump. This column is excerpted from his latest book.

Rodney W. Kennedy currently serves as interim pastor of Emmanuel Freiden Federated Church in Schenectady, N.Y., and as preaching instructor Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump. This column is excerpted from his latest book.

Related articles:

The Trump Card: How white evangelicals are being played | by Joel Bowman Sr.

Understanding the evangelical civil war | Analysis by Alan Bean

From 2016 to 2020, Trump grew in support from white evangelicals