In any other year, the following fact would have been a minor footnote in a story about United Methodists electing a gay male pastor as bishop in defiance of the denomination’s official ban on gay ministers: Cedrick Bridgeforth is a graduate of Samford University.

That Baptist-affiliated school in Birmingham, Ala., has made national headlines itself recently by doubling down against same-sex relations and same-sex marriage.

Bridgeforth’s recent election as a Methodist bishop is notable because it cuts to the heart of the schism rending the United Methodist Church. With support from the global reach of the UMC, traditionalists in the nation’s second-largest Protestant denomination in 2019 managed to pass policies that tightened restrictions against affirmation of same-sex relations and ordination of same-sex couples. That is not the majority opinion of United Methodists in the United States, however, which has led to three years of COVID-delayed fighting about the future of the denomination.

Bridgeforth now unwittingly finds himself at the intersection of the LGBTQ inclusion debate among both Baptists and Methodists.

Delegates to United Methodist regional conferences in the United States have made their displeasure known as they twice now have elected bishops who would not pass muster with the traditionalists’ rules. And faced with other rulings not in their favor, many of the traditionalists are leaving the denomination and forming their own new group.

Bridgeforth now unwittingly finds himself at the intersection of the LGBTQ inclusion debate among both Baptists and Methodists. In many ways, those two stories are the same story only in reverse.

Baptists and Methodists

While U.S. Methodists who are open to LGBTQ inclusion appear to have won the day in the United Methodist Church in America, the opposite was true in the Southern Baptist Convention. But the outcome of a different theological schism paved the way for that difference: Women in ministry.

While the UMC embraced women in ministry — but not without controversy — the SBC took a hardline stance against women, which was one factor in its own schism that led to formation of the Alliance of Baptists and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. The most theologically conservative part of the SBC won control of the denomination, which is what traditionalists in the UMC thought could happen there. But instead, it now is the United Methodist traditionalists who are breaking away.

The question of LGBTQ inclusion is not fully resolved in either Methodist or Baptist life. Only the smallest of the splinter groups of the SBC, the Alliance, is fully inclusive. CBF has taken torturous steps to try to keep a middle-ground peace on the issue, while the SBC has become more hardline in its total ban on all things LGBTQ.

That is the context in which Bridgeforth’s alma mater is currently generating controversy — revising its policies on what churches and ministries will be officially welcome on campus and what student groups will be allowed. President Beck Taylor, who is in his second year at the helm there, has said the university welcomes all students but cannot in any way endorse same-sex relations or same-sex marriage.

Diverse alumni perspectives

That has thrilled the conservative side of his alumni base and outraged the progressive side of his alumni base. And the fact that both sides exist speaks to the unity in diversity that once was a hallmark of the Alabama school.

The fact that both such sides exists speaks to the unity in diversity that once was a hallmark of the Alabama school.

Samford has produced Al Mohler, the extremely conservative president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and arch opponent of anything LGBTQ-related. Yet Samford also produced Bridgeforth, who went on to earn a master’s degree from Claremont School of Theology and a doctorate from Pepperdine University, on his way to becoming a United Methodist pastor and nonprofit leader.

Samford produced Adam Greenway, until recently president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and a noted conservative leader in the SBC. Yet Samford also produced Amanda Hambrick Ashcraft, executive minister at Middle Church in New York City, one of the most progressive and outspoken congregations in America on LGBTQ inclusion and other social justice issues.

The comparisons could go on for many more paragraphs. The 200 Samford alumni who recently signed an open letter protesting Samford’s restrictions on LGBTQ inclusion could be matched with another 200 alumni who would gladly sign a letter applauding the university’s stance.

And this kind of parity has a long history at Samford.

Herschel Hobbs, legendary pastor of First Baptist Church of Oklahoma City and one of the most influential SBC leaders of all time, was a Samford graduate. But so was Randall Lolley, the president of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary who was the first to fall victim to the SBC’s “conservative resurgence” and went on to become a leader in the formation of CBF.

Samford’s alumni roster includes a Who’s Who of key pastors and leaders in CBF life, just as it also includes a Who’s Who of key pastors and leaders in SBC life — pastors who might not agree on much other than the birth, death and resurrection of Jesus.

Can such diversity exist today?

Increasingly, though, such diversity may be unlikely because of the way universities must position themselves in terms of modern politics and theology. Samford, for example, relies on a steady stream of students from the youth groups of huge SBC churches in the South that are deeply conservative. Alienate those churches and you cut off your student recruitment pipeline. Not to mention donor base.

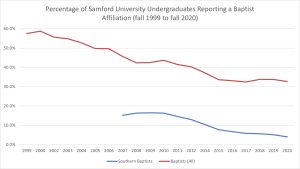

Graph produced by David R. Bains at ChasingChurches.com. Source for data: Quick Facts sheets published each year by Samford University. Initially in print form, in more recent years online. For the most recent ones see Institutional Research & Analytics Reports, https://www.samford.edu/departments/institutional-effectiveness/reports

But there’s one more factor at play here that affects not only Samford but all denominational schools today: Fewer of its students are Baptists than ever before. Denominationally affiliated schools now seek to attract students far beyond denominational borders. Ideology, culture and reputation have become more important than denominational label.

This fact has been documented by David Bains, a historian of religion and architecture in the United States, who teaches biblical and religious studies at Samford. He published a graph tracking the percentage of Samford undergraduates who reported a Baptist identity from 1999 to 2020.

The total number of students who identified as any kind of Baptist declined from nearly 60% in 2000 to about 33% in 2015, he found. And the total number of students who identified as Southern Baptist dropped from 16.5% to 4%.

Bains cites changes in the way student data is reported as one factor in the drop, as well as the possibility that students attended Baptist churches but didn’t realize they were Baptist because the denominational label didn’t appear in the name.

Living with contradictions

And then there are the students like Bridgeforth, the first openly gay man to serve in an episcopal role in the United Methodist Church.

Bridgeforth wrote an award-winning book about his childhood, his faith, his grandmother and his coming out story: Alabama Grandson.

In publicity for the book, he explained: “I did not realize how much I had to lose until I lost it all. In taking the painful journey of putting my life back together, it was obvious that who I had portrayed myself to be was never going to last. I had to find a way to be authentic in expressing my fullest and truest identities and know that the contradictions that come together to form me have always been present and will always be the best parts of my story.”

Related articles:

United Methodists elect married gay clergyman among 13 new bishops who represent many other firsts