In a media-saturated world filled with choices, some people have turned to what is known as “fandom” to find identity, meaning and purpose for life. In churches, some have substituted being a fan for being a follower of Jesus. Fandom has filled in the gaps created as fewer people seriously follow the teachings of Jesus.

“Fandom” may be defined as the state or condition of being a fan of someone or something. Fandom may include persons, teams, fictional series. The collection of such fans is considered a community or subculture. For example, there’s the Breaking Bad Fandom, the Harry Potter Alliance, or the Fighting Tigers of LSU.

What I’m suggesting here is that many churches now take on the identity of fandoms — much like sports teams and movie franchises.

Scholars in communication, media, cultural and rhetorical studies have produced a wealth of material about the nature of fandom. Yet fandom scholars have not paid much attention to the relationship between churches and fandom.

The theological problem with fandom

Theologically, “fandom” sounds antithetical to the concept of being a follower of Jesus. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says clearly that following him will not be easy. Jesus didn’t come to create “fans,” but to call into existence a church that is the alternative to a world of violence and lies.

“Jesus didn’t come to create ‘fans,’ but to call into existence a church that is the alternative to a world of violence and lies.”

Paul confesses that he wants to know Jesus and the power of his resurrection more than he wants anything else in the world. In the epistle to the Hebrews, Christians are upbraided for departing from the faith, for forsaking the assembling of themselves in worship and for falling away.

Scripture is clear. Church is not a cheering squad, but a called community of holiness. Church makes little sense if we are not called to a life of holiness. Across the centuries, the church has attempted to be a witness to the holiness of God as made known in Jesus.

This results in a way of life more than being super fans.

The nature of gathering

The nature of the church as a people gathering from the four corners of the earth speaks against the concept of the church as a fandom.

The homogenized gathering of people who look alike, who are from the same socioeconomic class, who think alike, who vote alike, and who are gathered to reassure one another that their beliefs are the only true beliefs is more a fandom than a church. I am not sure who would have the most trouble gathering on Sunday morning, a liberal Democrat at an evangelical church or a conservative evangelical at a liberal church.

If you are a Christian, there is a cross to bear. Being a fan suggests standing on the sideline. Being a follower of Jesus insists on personal involvement. We gather in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit to worship God, not to attack and defame enemies.

Fandom offers identity

Fandom creates an identity. In sports fandoms, fans wear the caps, the jerseys, the colors of the fan object. You have no difficulty identifying the fan at a football game. There’s likewise no confusion about the identity of the fans at an evangelical church.

They wear the T-shirts, sport the bumper stickers, share a common fan language.

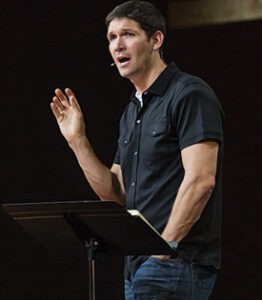

Matt Chandler

One of the problems with fandom in the church is the propensity to create cult-like followings around both personalities and issues. This is why Matt Chandler of The Village Church and Acts 29 Network made national headlines this week. The celebrity pastor confessed to some inappropriate behavior, which shook the confidence of the tens of thousands of people who follow and admire him.

Likewise, Chandler has become well known for espousing certain doctrines and ideologies that define conservative evangelicalism today — which sets him on an impossible pedestal. His potential downfall is seen as the downfall of the church because, in the minds of many of his followers, he is the church.

Fandom breeds tolerance of favoritism

Jesus was baptized by John to identify with sinners. The identity of evangelical fandoms around cultural and social issues is the opposite of the approach of Jesus. And the identify of progressive Christian fandoms around standard-bearers of cultural and social issues faces the same critique.

This allows fandoms to be captured by lingering forms of systemic sin without seeing the problem. For example, in the fandom of churches, there’s a lingering sense of the systemic racism that was the originating impetus behind the evangelical movement. Church and sports mirror the same forms of systemic racism that always have haunted our nation. Even in progressive churches, the sins of sexism and classism thrive.

Racism and sexism and homophobia all feel safe and justified because they are values of the fandom.

Fandom is all about affects

Fandom festers, in part, through high emotional content. The most obvious and pervasive feature of the “fandom” created by preachers in many churches is the highly visible, media-savvy and entertaining performances. This normalization of a frenetic chaos and hyper-activism is rooted in a deep but debilitating populism.

“Being a fan requires little more than maintaining emotional intensity.”

Being a fan requires little more than maintaining emotional intensity. Like pro wrestling fans watching the “fake” performances, true believers get caught in the spectacle. The same emotional atmosphere is recreated in a church fandom.

This emotional intensity continues during the week as people discuss the event and relive the event. The event, the performance, becomes the essence of what it means to be a fan.

Fandom requires a fan-object

The commitment of these “fans” is to a “fan-object.” Fandoms in Christianity include a variety of fan-objects, most often high-profile pastors or leaders of large parachurch ministries.

The fan-object is the person whom fans love, admire and follow. The leadership model for fan-based churches is charismatic.

“Charismatic leadership,” according to rhetorical scholar Patricia Roberts-Miller, “is a relationship that depends upon ‘identification,’ in which a person or group of people feel themselves to be ‘substantially one’ with the leader.” In churches, the leader may be “sublime,” meaning he is beyond anything negative, a pure expression of the true identity of the followers. This is called “ultimate identification.”

The pastor in this case is not the leader; he is the congregation embodied.

Political scientist Ann Wilder says in charismatic leadership communities followers perceive the leader as “superhuman,” they “follow blindly,” they “unconditionally comply,” and they give “unqualified emotional commitment.”

In a charismatic authority relationship, dissent from that person’s decisions is impossible because it would imply that the leader is flawed and has less than perfect judgment. Even if there is evidence that the charismatic leader may be wrong, evil or criminal, there can be no dissent from his fandom because the entire apparatus is grounded in irrational consent.

“The leader may not know what he is talking about, but he is the authority for the church.”

In a church, fandom requires an attachment to the fan-object, often the senior pastor as the anointed leader. The leader doesn’t need academic credentials. The leader may not know what he is talking about, but he is the authority for the church.

The cure for fandom

Although fandom may be found in all kinds of churches, it works best in non-liturgical churches with a highly oxygenated emotional ethos. Liturgical churches have far less emphasis on the personality of the pastor or priest. Sacramental churches are more likely to produce servants than superstars.

A congregation trained in the liturgy of the church will not be led into secular political rants by the pastor or priest.

The cure to fandom in the church is a renewed emphasis on liturgy and worship more than personality and oratorical prowess. There is a way to build spiritual community without building a fandom.

Rodney Kennedy

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor in New York state and serves as a preaching instructor at Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump.

Related articles:

A conversation with Ben Kirby, author of PreachersNSneakers | Opinion by Maina Mwaura

What should we think of celebrities for Jesus? | Opinion by Katelyn Beaty

I lived in the culture of ‘The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill,’ and there’s one part of the story that’s wrong | Opinion by Rick Pidcock