In an exceptionally rare move, the administration of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary has used its annual report to the Southern Baptist Convention to accuse its former president of theft.

Although rumors and intimations of the current seminary administration’s displeasure with former President Paige Patterson and his wife, Dorothy, have circulated for months, the new item released in the SBC’s 2021 Book of Reports is the most explicit accusation yet made public.

Some of this came to light in earlier litigation between the seminary and the Pattersons over control of the Harold E. Riley Foundation. However, because a settlement was reached in that case before the trial began, details of the accusations against Patterson were not publicly documented and Patterson was spared from being compelled to testify.

That shrouded secrecy all changed Friday, May 29, when the SBC Book of Reports was released online.

The accusations

Two years ago, at the 2019 SBC annual meeting, messenger Benjamin Cole made a motion that was referred by the convention to Southwestern’s trustees. That motion stated: “That this convention request the trustees of SWBTS to authorize the seminary president and legal counsel to pursue through all means necessary the lawful recovery of seminary property, both tangible and intangible, including furniture, household furnishings, artifacts, antiquities, memorabilia, audiovisual and computer equipment, and any official records that may have been removed from the presidential home or other campus facilities without authorization between the dates of May 30, 2018, and February 27, 2019.”

Dorothy and Paige Patterson

Patterson was fired as Southwestern’s president May 30, 2018. The complete severing of ties between the seminary and Patterson came after trustees first adopted a more gracious transition out of office that was met with fierce criticism as being too kind. Patterson had been accused of covering up and making light of allegations of sexual abuse of women.

Now, Southwestern’s administration — led by new President Adam Greenway, who has been on a three-year apology tour trying to mend fences with donors and alumni and other stakeholders — has laid out specific charges against Paige and Dorothy Patterson.

After the termination, Southwestern “learned that the Pattersons had improperly removed boxes of documents that belonged to the seminary from the president’s home (then called Pecan Manor) on campus. The documents included confidential donor information, student records, institutional correspondence, financial records, historical files, and meeting and convention records. Through legal counsel, over the course of several months, the seminary repeatedly requested that the Pattersons return these documents. In doing so, the Seminary specifically identified the records that needed to be returned.

“Rather than return the records, the Pattersons advised the seminary that the documents had been ‘purged.’ At the same time, the seminary has expended significant energies in reviewing and cataloging the archives of former President Patterson in order to return to their rightful owner items that do not belong to the seminary. To date, the records that the seminary has requested the Pattersons return have not been returned. Instead (and contrary to the Pattersons’ representations that seminary records had been purged), the Pattersons have continued to use institutional records for their own personal benefit and to the detriment of the seminary.”

The report also accuses the couple of theft of specific items from a collection of artwork, taxidermy and firearms donated to the seminary by Perry Bolin in 2009. Paige Patterson was known on campus for his love of big game preserved through taxidermy and displayed not only on campus but specifically in the president’s office.

Paige Patterson posing in the president’s office at Southwestern with Terry Turner, a Texas pastor.

After Patterson’s firing, the seminary administration determined no longer to display most of the Bolin collection. “In 2019, the seminary worked with the Bolin family to transfer ownership of much of the collection to a third party since the seminary did not have plans to publicly display again the taxidermy on campus,” the report explains. “As an inventory of this collection was taken beginning in 2019 and lasting into 2020, it was discovered that several items could not be located. These missing items included artwork, taxidermy and antique firearms.”

Then this bombshell: “Through pictures posted to social media, the seminary learned that at least one of the missing paintings is hanging in the Pattersons’ new home in Parker, Texas. On multiple occasions, legal counsel for the seminary has contacted the Pattersons’ legal counsel to request the items be returned. As of the time of this response, the missing items have yet to be returned to the seminary.”

Patterson response

Four days after the allegations in the Book of Reports were published, Baptist Press, the SBC’s internal news service, published comments from Paige Patterson denying the accusations against him and his wife.

“I do not think the courtroom or the press is the place where Christians need to discuss their differences,” Patterson told BP, adding that the interview would be his only public comment on the matter. “That’s the reason why you’re the only one I have talked to. We’re responsible for working out our differences with other Christians. I’m very disappointed that we seem to be having trouble doing that.”

In his telephone interview with BP, Patterson denied that items belonging to Southwestern were improperly taken, saying: “not to my knowledge.” He said documents described as “purged” were “taken care of,” with “nothing of value” being destroyed. Patterson also said he and associates had not received a confidential donor list or attempted to divert gifts from Southwestern to the Sandy Creek Foundation.

BP then quoted President Greenway, the chairman of the trustee board and two other witnesses to verify the claims Southwestern has made against the Pattersons.

Trustee Chairman Philip Levant explained that the board “unanimously approved” a draft of the response to the motion during its fall 2020 meeting and that the trustee executive committee approved the final response.

“We emphatically stand by our response as it is truthful and verifiable,” Levant said in a statement to BP. “I urge all Southern Baptists to carefully read it in its entirety to understand the scope of the challenges faced by this institution in the wake of the former president’s rightful dismissal.”

Greenway implored: “Southwestern Seminary has told the truth.”

Greenway implored: “Southwestern Seminary has told the truth.”

BP also quoted Bart Barber, pastor of First Baptist Church of Farmersville, Texas, and a member of the seminary trustee executive committee that voted to fire Patterson. Barber wrote on social media over the weekend that he had “first-hand knowledge” of some of the information in the seminary’s response to the motions. “To my knowledge, every word of the @SWBTS report is true.”

Paige Patterson was scheduled to preach at First Baptist Church of Dallas on Sunday morning, May 30. Although he didn’t directly address the accusations against him that had been published two days earlier, he did reference “the lynch mob that I saw out there trying to get hold of me.”

After Patterson’s termination from Southwestern, some SBC officials urged SBC churches not to invite him to preach for them, as noted by a weekend report on the Missouri Word&Way: “Trustees terminated Paige Patterson for cause, publicly disclosing that his conduct was ‘antithetical to the core values of our faith,’” SBC President J.D. Greear told the Houston Chronicle in January 2020. “I advise any Southern Baptist church to consider this severe action before having Dr. Patterson preach or speak and to contact trustee officers if additional information is necessary.”

Word&Way also reached out to Ben Lovvorn, executive pastor at First Baptist, Dallas, for comment about Patterson preaching in light of the allegations by SWBTS.

“Dr. Patterson has actually been scheduled for several months to preach tomorrow,” Lovvorn said. “The Pattersons are longtime members of First Baptist, Dallas. Dr. Patterson served as an associate pastor of the church in the 1970s and ’80s and teaches a Sunday School class at the church.”

Robert Jeffress

The church’s outspoken senior pastor, Robert Jeffress, introduced Patterson with praise for his former leadership at Southwestern: “Paige did a marvelous job there as president of the seminary.” He then called the co-architect of the conservative takeover of the SBC “the Winston Churchill of the Southern Baptist Convention.”

Patterson, in turn, called Jeffress “the pastor with the greatest courage of any pastor I’ve run across in 25 years.”

The Sandy Creek Foundation

The new details from Southwestern’s administration add to an already bizarre tale that implicates the Pattersons in attempts to gain personal benefit from donors and funds previously allocated to the seminary. That was the heart of the legal case with the Riley Foundation, which held a $15 million corpus intended by Hal Riley before his death to benefit Southwestern and Baylor.

The Pattersons and several others — including some who were current and former seminary trustees — were accused of illegally redirecting that money from the two schools to the Pattersons’ own foundation, the Sandy Creek Foundation. Not only that, they were accused of attempting to take control of the company Riley founded, Citizens Inc., a $300 million publicly traded company.

The Sandy Creek Foundation is an IRS-approved public charity that lists Paige Patterson as its president and Dorothy Patterson as its vice president. Its stated mission is “to promote biblical truth and values through local, national and international avenues. … The ultimate goal of the Sandy Creek Foundation is the evangelization of those who are lost and the advancement of the kingdom of God.”

There is no public record of the organization’s finances since Patterson’s firing.

The most recent IRS Form 990 on file is from 2018, the year of Paige Patterson’s firing. If IRS forms have been filed since then, they have not been posted on the IRS website. Therefore, there is no public record of the organization’s finances since Patterson’s firing. Sometime between 2017 and the end of 2018, the name of the foundation was changed from Patmos Evangelistic Association to Sandy Creek Foundation.

In Baptist history, Sandy Creek was the name of an 18th century Baptist church in North Carolina from which the more informal and revivalistic branch of Southern Baptists trace their roots. Historians often contrast the Sandy Creek tradition with the Charleston tradition, which represents a more formal and liturgical form of worship.

The 2018 IRS form shows the Sandy Creek Foundation received a grant or contribution of $5.4 million that year, although the source is not named. It also lists $1.5 million in assets or real estate and equipment. It also notes that the foundation owns a “library collection of approximately 31,300 volumes, including an estimated 3,500 antiquarian volumes. This collection is used to promote biblical truth and values.”

In 2018, the Sandy Creek Foundation reported only $1,448 in gifts and grants to assist other organizations. The bulk of its reported expenses were related to personnel — the Pattersons and their son and one other person — and benefits and travel. The IRS form shows $92,000 in travel expenses that year.

Brad Jurkovich preaching in chapel at Southwestern Seminary in 2018.

The IRS form lists seven people beyond Paige and Dorothy Patterson as officers of the organization: Charles H. Armstrong Jr., a Dallas accountant, who is treasurer; Scott Colter, former chief of staff to Patterson at Southwestern and now a director of strategic initiatives at Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary as secretary. Colter also serves in a leadership role with the Conservative Baptist Network. The IRS form also lists five directors: Brad Jurkovich, pastor of First Baptist Church of Bossier City, La., and leader of the Conservative Baptist Network; Linda Behan, a Fort Worth businesswoman who was a previous donor to Southwestern; Mark Howell, the Pattersons’ son-in-law and former senior pastor at Hunters Glen Baptist Church in Plano; Armour Patterson, Paige and Dorothy’s son who is an author; and Paul Spann, a Dallas layperson and former director of the Riley Foundation.

Tax records for Collin County, Texas, show the Sandy Creek Foundation owns real estate in Parker, Texas, with a current tax-assessed value of $1,285,688. That is described as a 7,700-square-foot single-family residence. County records show the property was purchased by the foundation on Aug. 20, 2018, three months after Paige Patterson was fired at Southwestern.

Collin County is located north of Dallas and is better known for its largest city, Plano, which is a suburb of Dallas. Parker is a more rural part of the same county.

More seminary accusations

In addition to accusations of theft of items from the seminary’s Bolin collection, the administration accuses the Pattersons of using confidential donor information for their own financial gain.

“In connection with its charitable giving efforts, the seminary developed a confidential donor list that identified every individual and entity that has made a gift or donation to the seminary,” the report to the SBC explains. “The Pattersons have continued to use the seminary’s confidential donor list in order to contact seminary donors to divert donations and gifts away from the seminary. The Pattersons’ actions have caused substantial financial harm to the seminary.”

Candi Finch

The report accuses former seminary staff member Candi Finch of being an accomplice to the theft of donor data. Finch previously served as professor of women’s studies at Southwestern and now works with the Sandy Creek Foundation as well as serving as associate professor of theology in women’s studies at Truett-McConnell University in Georgia.

The seminary report states: “Within days of President Patterson’s termination, Candi Finch emailed the seminary’s confidential donor list to a private email address associated with an assistant to the Pattersons. The donor list identified all individuals and entities who have made donations to Southwestern Seminary.”

It further charges: “Using the seminary’s confidential donor lists, the Pattersons undertook a scheme to contact seminary donors in attempts to convince the donors to withhold gifts from the seminary and instead make donations to the Sandy Creek Foundation.”

For her part, Finch has been active on Twitter since May 29 defending herself and the Pattersons.

In one post, she wrote: “Brothers and sisters, when is this going to stop? @swbts trustees, can you with a clear conscience stand behind the slander in this year’s book of reports? What has been so disillusioning for me since 2018 is the people who know the truth and are unwilling to stand up for it.”

Current seminary officials say the Pattersons convinced a donor to redirect a $5 million gift from the seminary to their foundation, used the seminary’s donor list to send out a mass mailing soliciting funds for their foundation, used the donor list to “spread misinformation regarding the seminary,” and attempted to convince another donor to change her will’s beneficiary away from the seminary to their foundation.

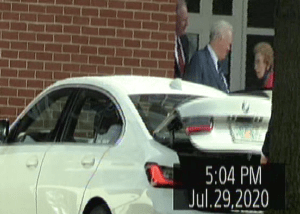

This photo, taken by a private investigator, was among a set mailed to seminary leaders and others. It shows Dorothy Patterson with Elizabeth Griffen in July 2020.

Paige Patterson and another unidentified man greeting Southwestern donor Elizabeth Griffin in July 2020.

In the last case, Baptist News Global was sent photographs taken by a private investigator showing both Pattersons traveling to Memphis, Tenn., by private jet during the height of the coronavirus pandemic and meeting face-to-face with the elderly donor, who is named in the SBC Book of Reports as Elizabeth Griffin. Griffin died in December, five months after the Pattersons’ July visit.

Financial statements reported by Southwestern via SBC Annuals and the SBC Book of Reports show that private gifts to the seminary have, indeed, declined since Patterson’s firing. The seminary reported $15,777,246 in private donations for the academic year 2017-2018, the last year Patterson was president. By comparison, the latest reports for academic year 2019-2020 shows private gifts to Southwestern totaling 9,827,249 — $6 million less than Patterson’s last year but still significantly more than any of the other five SBC seminaries.

Finch, in her series of tweets last week, said the Pattersons have done nothing wrong and have, in fact, helped raise money for the seminary even after Paige Patterson’s firing.

“Regarding the $5 million check, the donor on his own requested the money be returned because he was disgusted by how the @swbts trustees had treated Dr. Patterson. This was a direct consequence of the trustees’ own actions,” she said.

The Patterson legacy at Southwestern

Meanwhile, Southwestern Seminary has experienced a steep decline in enrollment since the beginning of the Patterson years. Once billed as “the world’s largest theological seminary,” Southwestern today is the next-to-smallest of the six SBC seminaries, based on student enrollment.

Southwestern Seminary campus in Fort Worth, Texas.

In the 2021 SBC Book of Reports just released, a chart of comparative enrollment data for the six SBC seminaries shows Southwestern reporting a 2019-2020 academic year enrollment of 1,126, based on the full-time-equivalent formula used by the SBC. That makes the Fort Worth school the smallest of the SBC seminaries except for Gateway Seminary in California, with an enrollment of 420. The year before Patterson became president, Southwestern reported an FTE enrollment of 2,381.

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kentucky is now the largest of the SBC schools, with a reported FTE enrollment of 2,762, followed by Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in North Carolina, 2,438; Midwestern Seminary in Missouri. 1,615; and New Orleans Seminary in Louisiana, 1,508.

The latest numbers from Southwestern actually show a gain from the prior year, when the full-time-equivalent reached a low of 1,029. In its peak years during the 1980s, Southwestern reported FTE enrollments of 3,700 or more.

Also at that peak, Southwestern enrolled more than 1,800 students in its master of divinity program, which in the latest report shows only 281 students enrolled. The M.Div. degree is the basic degree offered by seminaries and divinity schools for pastor training nationwide.

When Patterson came to Southwestern as president, the school was graduating about 250 M.Div. students annually. By the end of his tenure, that number had dropped to 112.

Southwestern also has become the second smallest of the six SBC seminaries by total nonduplicating headcount.

Southwestern also has become the second smallest of the six SBC seminaries by total nonduplicating headcount, meaning the number of unique students enrolled whether full time or part time. In the latest data, Southwestern reports 3,907 individuals enrolled — while Southern Seminary is the largest school with 5,659.

The reports on nonduplicating headcounts also reveal a key trend in SBC theological education — all six seminaries enroll large numbers of non-SBC students. Such students pay a higher rate of tuition and are not supplemented in their expenses the same way as students who are members of SBC churches.

For example, 20% of Southwestern’s big-number enrollment (3,907) constitutes non-SBC students. Southeastern Seminary in North Carolina leads the six schools in enrollment of non-SBC students, which account for 32% of its headcount.

Another factor for all the SBC seminaries is the creation over the last two decades of undergraduate programs that offer certificates, associate degrees and bachelor’s degrees — previously the province of Baptist colleges and universities, not SBC seminaries.

Patterson, during his tenure at Southeastern Seminary from 1992 to 2003, pioneered this innovation to expand the seminary’s reach, increase its enrollment and maintain funding from the SBC Cooperative Program even as graduate-level enrollments already were declining.

Patterson came to the Southeastern post from the presidency of Criswell College in Dallas — a Bible college created by and closely affiliated with First Baptist Church of Dallas and named for its then long-time pastor, W.A. Criswell. At the time of its founding, Criswell College was seen as a more conservative alternative to Southwestern Seminary, which was considered by Patterson and his allies as leaning toward liberalism.

Ultimately, Patterson was fired from leading Criswell College in 1991. Less than a year later, he was installed as president at Southeastern Seminary — following a line of seminary administrators he had targeted as liberals in his campaign to gain control of the SBC.

Patterson was fired from leading Criswell College in 1991. Less than year later, he was installed as president at Southeastern Seminary.

Meanwhile, back in Dallas, one of Patterson’s allies from First Baptist Church, Ralph Pulley, was leading a campaign against Russell Dilday, who was president of Southwestern Seminary. Pulley, who was a deacon at First Baptist, Dallas, and who was placed on Southwestern’s trustee board through the machinations of the Patterson-Pressler “conservative resurgence,” became Dilday’s staunchest opponent, leading to Dilday’s controversial firing by conservative trustees in 1994.

A decade later, after Patterson came back to Texas to lead Southwestern Seminary, one of his trustee allies became Ralph Pulley’s son, Thomas Pulley, by then also a deacon and leader at First Baptist, Dallas. Thomas Pulley was one of the Southwestern trustees involved with Patterson in a reported attempt to gain control of the Harold E. Riley Foundation.

What’s next?

How, or if, any of this will be addressed at the SBC annual meeting in Nashville in mid-June is not clear. There already is a dispute going between Southwestern’s administration and the SBC Executive Committee about who can remove a convention-elected trustee.

That dispute stems from the Riley Foundation lawsuit. In October 2020, seminary trustees Charles Hott, Thomas Pulley and Randy Martin reportedly were denied access to trustee meeting materials because board officers deemed they had a conflict of interest by serving on the seminary board and the Riley Foundation board.

Legal counsel for the SBC Executive Committee wrote to Southwestern’s legal counsel to complain about this, asserting that “under Texas law a trustee has the right to participate in meetings of the board as long as he holds office.”

Southwestern’s administration, trustee officers and legal counsel believe the seminary board must be allowed to manage its own affairs or risk running afoul of both Texas law and accreditation standards. The SBC Executive Committee’s leaders, officers and legal counsel believe a “sole member” designation inserted in every SBC entity’s bylaws reserves that right only for the SBC, not for the board itself.

As a subpoint to this debate, Southwestern claims even if the SBC has that right, it is a right that belongs only to the convention in annual session, not to the Executive Committee. The Executive Committee claims it has full authority to act on behalf of the convention between annual meetings, including on issues of trustee removal or suspension.

Southwestern’s published report to the convention does not appear to ask for convention messengers to rule on any of these matters, although any individual messenger could go to a microphone and make such a request.

This story was updated at 7:15 p.m. Central Time on Tuesday, June 1, to include additional comments from Paige Patterson.

Related articles:

Paige Patterson out at Southwestern Seminary

Seminary removes stained glass windows celebrating conservative takeover of SBC