Last week in my Friday Roundup, a free summary of the week’s news that goes out by email, I told the story of my late friend Carl McKeever, whom I held up as an example of a true patriot.

Much to my surprise, I received an email from a reader who had a fascinating addition to my story about Carl’s service in World War II. This reader’s father, like Carl, also had a connection to the sinking of the SS Leopoldville by a German torpedo on Christmas Eve 1944.

The reader’s father, Orland Brewster Herrington, as an adult lived just one Dallas suburb over from Carl, both were Baptists, yet it appears the two men never knew each other.

Carl McKeever

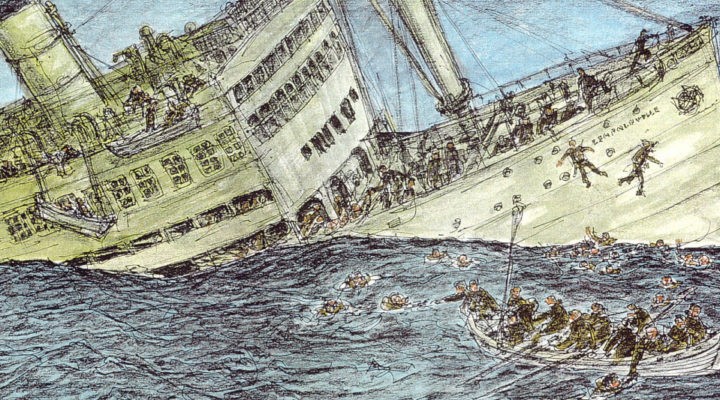

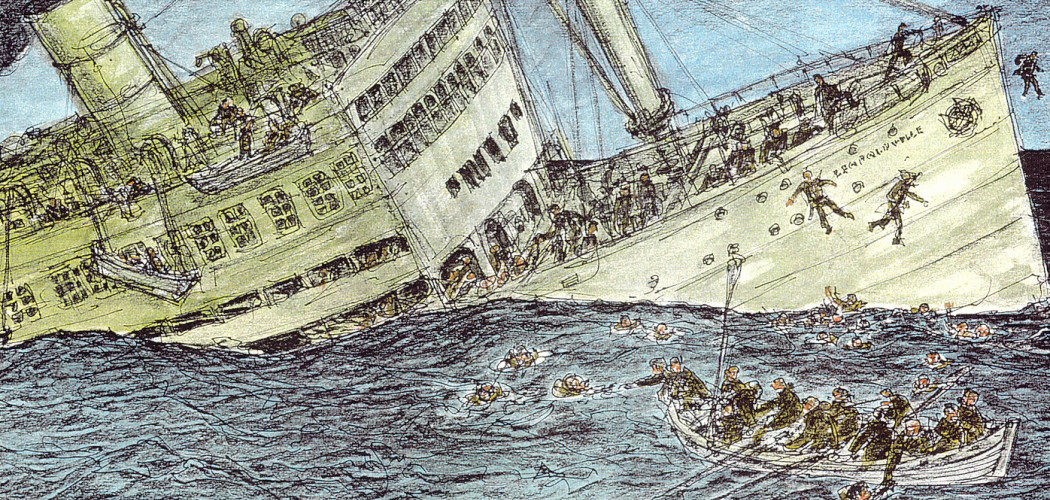

Carl was 19 when he found himself crossing the English Channel on Christmas Eve aboard the HMS Cheshire, a British cruise ship that had been repurposed as a troop transport ship to help with the war effort. The Cheshire steamed alongside a larger ship, the SS Leopoldville, escorted by a flank of four destroyers. Just 5 miles offshore from Cherbourg, France, the SS Leopoldville was torpedoed by a German U-boat.

On that afternoon, 762 soldiers and officers were lost, despite rescue efforts by those on the Cheshire and the accompanying destroyers. Other ships in Cherbourg harbor were not able to come to the rescue quickly because their crews were ashore celebrating the holiday.

Carl and the other soldiers of the 66th Infantry Division were ordered not to tell anyone about the sinking of the ship, and their letters home were censored by the Army during the rest of World War II. After the war, the soldiers reportedly were ordered not to talk about the sinking of the SS Leopoldville or their GI benefits as civilians would be canceled.

Carl abided by that policy for more than 60 years, never speaking much of his military service even to family until just a couple of years before his death, when the grandchildren began digging and asking insistent questions. I heard the story from him just a couple of weeks before his death.

It was on the backs of PFCs like him that the 66th Division Panthers guarded the German submarine base pockets that were left after the D-Day invasion and fought at the Battle of the Bulge. And it was PFCs like Carl who kept the peace after the war in Germany and Austria.

Now, here’s the rest of the story.

O.B. Herrington

Orland Brewster Herrington was known by the initials O.B. He was 29 years old on that fateful Christmas Eve 1944. And he was serving in Cherbourg, France, as an army cook. He had experienced a call to preach before the war, but he had not even graduated from high school, so he found his way to the Army.

At Christmastime 1944, O.B. and others from his unit were on leave for rest and relaxation. But that proved to be short-lived, as they soon were called into urgent duty.

When the SS Leopoldville was struck just 5 miles from shore, many soldiers onboard were killed instantly. Others jumped into the 48-degree water and froze to death or were rescued by the other boats in the flotilla and brought to shore at Cherbourg.

Before his death in 1997, O.B. wrote out his memory of what happened next.

“The two (surviving) ships came on into Cherbourg and began notifying units in the area of their needs. Our Company I was called into service to haul the injured to a hospital some distance away and to haul the dead to a morgue. Those who were just in need of warm, dry clothing and food were taken to various units where they could find assistance. All day on Christmas Eve, this is what our men were doing.”

In his job as an Army cook, O.B. also was assigned to work with several German prisoners of war in the kitchen. He determined not to tell the Germans what had happened or how his unit was responding to the need. His reasoning: “Some of them may have even been involved in placing the (explosives) in the channel earlier.”

Leopoldville illustrations by Richard Rockwell via Leopoldville.org

At the time, U.S. soldiers were told the Leopoldville had been sunk by an underwater mine; in reality, it had been sunk by a torpedo from a German U-boat.

The Leopoldville sank about 8:30 p.m. The rescue effort played out over the next several hours, both at sea and on shore.

O.B. picks up the story again: “That night, after the evening meal was eaten and everything was clean and ready for the next morning, I went to my tent. I was sitting on my cot thinking of the events of the day and feeling concern for the men who had been in the ship that was destroyed. I was in a sad mood and was thinking that one of the men in our POW stockade may have placed the bomb in the English Channel which had eventually done what our enemy hoped it would do — it had destroyed lives and property.

“Suddenly, I was roused from my thoughts by a noise at the tent’s entrance. I looked up, and there was Paul Kruger (one of the German POWs) just inside my tent. He must have sensed my concern. He said that a guard was just outside. He had asked the guard to bring him to my tent when another guard was there to relieve him. I asked Paul what he wanted. He said the prisoners wanted me to come to their tent. I did not really want to go. My feelings at the moment were not too friendly toward any Germans.”

The American soldier went to the tent of the German POWs. And that is when something unexpected and holy happened.

Nevertheless, the American soldier went to the tent of the German POWs. And that is when something unexpected and holy happened.

“As Paul and I entered the POW tent, someone turned off the only light they had in the tent,” O.B. recalled. “Two prisoners began to light little candles on an improvised Christmas tree, and all the prisoners began singing ‘O Christmas Tree’ in their German language. The candles made enough light that Paul could see to escort me to the head of a table that had been improvised by placing lumber on sawhorses and covering the table with bleached mattress covers for a tablecloth.”

There the POWs seated O.B. in what he called “the best old chair they had,” while the prisoners were seated on benches and old chairs around the table and in rows near the table.

“All of them continued to sing several Christmas carols. I could not understand many of the words, but the melodies were familiar. On the table were German mess kit plates for everyone. On the plates were some pieces of hard candy and some cookies from rations which the prisoners had evidently saved for the occasion.”

Then, one of the prisoners asked O.B. to read the Christmas story from the Gospel of Luke, him reading one verse in English followed by another reading the verse in German.

Then, one of the prisoners asked O.B. to read the Christmas story from the Gospel of Luke.

“We stood at the head of the improvised table with the meager tokens of food before us and solemnly read about the birth of Jesus in a manger in Bethlehem so many years ago,” O.B. recalled. “When we finished, Paul wanted me to lead in prayer. By this time, my emotions had just about reached the overflowing point. But I led in prayer and sat down at the head of the table.”

The experiences of that Christmas Eve changed O.B.’s attitude and his life.

“Several lessons were learned during the experience in the prisoners’ tent that Christmas Eve in 1944 at Cherbourg, France. First, these were men just as our troops were men. These men had souls just as we did. Many of these men seemed to be Christian men just as many of our men were. Many of these men had not wanted war any more than most of us did not want war. Yet, here we were, having been taught to hate one another and to fight to death for our ideals.

“These men had become our prisoners of war, yet we had just joined our minds and our voices to celebrate the coming of the Prince of Peace. There was so much irony in all of this that I was overwhelmed.

“But the big lesson that remains to this day is that we cannot afford to harbor hate in our lives. Hate will eventually do as much harm to the hater as to the hated. It will eat away at one’s very soul. Therefore, I could hate war without hating individuals who were involved in it. I did not have to blame Paul — even if he may have planted that bomb. I needed to be a better Christian than that. So, I was a changed person in many ways from the one who had gone with Paul to the POW tent that night.”

Paul Kruger, by the way, later saved O.B. from drowning in a river, and they corresponded for years after the war.

“I could hate war without hating individuals who were involved in it”

The young American who had felt a call to Christian ministry but hadn’t graduated high school determined that night to become more involved in the spiritual care of both troops and prisoners of war. Since he had landed in France on D-Day, O.B. had seen only one Army chaplain, because most were assigned to the front lines.

So he took a survey of the troops and prisoners at his camp and began to organize religious services for both. There, the Americans and the Germans sang hymns together accompanied by a borrowed field organ and holding hymnals a chaplain helped them secure.

And O.B. began to preach. He described his intent as to offer “sermons that would be helpful to as many as possible without getting into specific denominational doctrines.”

After the war, O.B. attended Baylor University, where he earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English and Bible. He served small rural churches that could not afford a full-time pastor and earned a living as an educator and administrator at the Corsicana State Home, Buckner Children’s Home, and as a consultant at Region 10 Education Service Center in Richardson, Texas.

If Carl and O.B. had known each other, they would have had a lot to talk about. For now, we’ll just have to let their lives speak to us.

Learn more about the Leopoldville disaster here.