Several years ago, a mission team of laypersons preached the morning sermon at First Baptist Church of Abilene, Texas. They had just returned from completing medical and construction projects at a small Christian hospital in the mountains near Chihuahua, Mexico.

Their stories of building much-needed medicine cabinets and relationships, repairing clinic doors and broken bodies, and salvaging discarded equipment and forgotten lives touched our affluent congregation profoundly. In one testimony, a family physician summarized how he viewed their missionary efforts in that needy setting: “Some will call what we did the ‘Social Gospel’; I just call it ‘obedience.’”

This mention of the Social Gospel more than a decade ago highlights a misunderstanding that has been perpetuated by evangelical leaders and churches for a century. Quite recently, in fact, a friend told me that the “true gospel” is salvation through Jesus Christ, and not just doing good works.

But I contend that the true gospel is social. It has a personal aspect, of course, yet the implications of the true gospel are social. The first and greatest commandment is to love God with all our heart, soul and mind — and, for Christians, that means loving Jesus as the Incarnate Word, the human face of God. But the second mandate, as ultimate as the first, is to love our neighbors as we love ourselves (Matthew 22:36-40) — which grounds the social nature of the gospel in the person of Jesus himself.

What is the Social Gospel?

The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology describes the Social Gospel as “a type of activist Protestantism which arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in industrial, urban North America.” The classic definition, however, came from a participant in the movement itself, theologian Shailer Mathews, who identified the Social Gospel as “the application of the teaching of Jesus and the total message of Christian salvation to society, the economic life, and social institutions . . . as well as to individuals.”

Overseer supervising a girl (about 13 years old) operating a bobbin-winding machine in the Yazoo City Yarn Mills, Mississippi, photograph by Lewis W. Hine, 1911; in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

More recently, in a conference at Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, the oldest Baptist seminary in America, Susan Hill Lindley explained how the Social Gospel differs both from secular efforts to help needy people and from Christian charitable practices. She said:

The Social Gospel (is) distinguished, on the one hand, from general … humanitarian work by the religious motivation behind its ideas and activities, and its insistence on connecting social ideals with the kingdom of God, at least partially realizable in this world. On the other hand, the Social Gospel (moves) beyond traditional Christian charity (by recognizing) corporate identity, corporate (or) structural sin and social salvation, (as well as by expressing) concern for individual sin, faith and responsibility.

Shailer Mathew’s definition that stresses how the Social Gospel speaks to societal as well as to individual life challenges the way Christians in the West often interpret the nature of discipleship. In a commitment to individualism, some American Christians assume that being Jesus’ follower only affects one’s personal relationship to God, and so they neglect applying the gospel’s demands to the larger world around them.

Perhaps this cultural loyalty is the reason many sermons focus upon pursuing the “deeper spiritual life” for the individual believer rather than partnering with others to do God’s work in the world. This theme of following Christ beyond oneself is revisited in Susan Lindley’s assertion that in addition to “individual sin, faith and responsibility,” the Social Gospel is concerned about “corporate identity, corporate (or) structural sin and social salvation.”

Perhaps many Christians, like my friend who talks about the “true gospel,” have associated the Social Gospel either with theological liberalism, secular humanitarian aid projects or persons they know who express an aversion — or even antagonism — toward evangelism. If so, they perhaps will be surprised to learn that the preeminent representative of the Social Gospel was a Baptist pastor and professor at a Baptist seminary — a Christian who had a deeply religious family heritage, a passion for helping needy people and an eagerness to share with them his faith in Jesus Christ. He was Walter Rauschenbusch, considered by some to have been a heretic and, by others, a modern prophet.

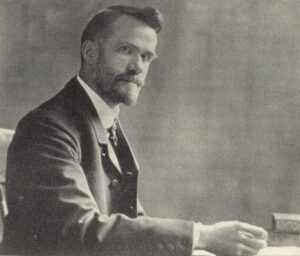

Walter Rauschenbusch, Social Gospeler

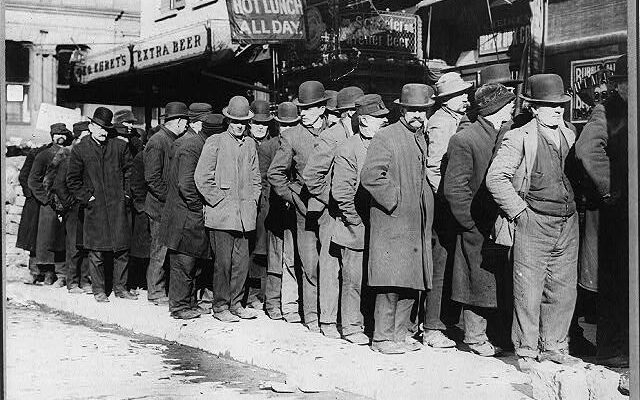

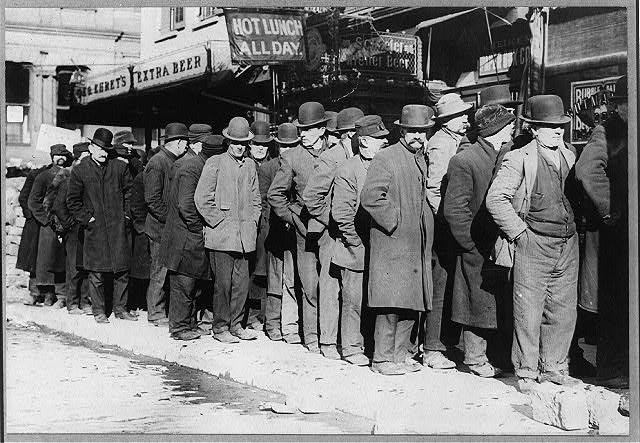

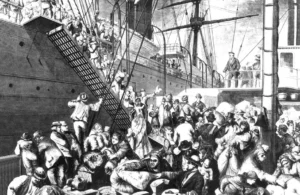

Walter was born in 1861 in Rochester, N.Y., the son of Caroline and August Rauschenbusch, German immigrants who came to the United States 15 years before his birth. As one historian explains, in the mid-19th century “thousands of German immigrants were pouring into the New World to live in its tenements, work in its sweatshops or join the lines of its unemployed.”

Walter Rauschenbusch

August Rauschenbusch didn’t work in a sweatshop or move his family into a tenement house, however. According to Christopher Evans, professor of the history of Christianity at Boston University, “soon after immigrating to the United States (August) broke ranks with a deeply rooted family heritage of German Lutheranism to embrace a conservative Baptist pietistic tradition,” a shift which eventually secured the German-Baptist missionary a respected professorship teaching German at the Rochester Theological Seminary. It was there, near the campus of the small Baptist school, where young Rauschenbusch spent his childhood.

Under the influence of his family, his church and the seminary, teenaged Walter became a Christian, an experience about which he later wrote: “It was of everlasting value to me. It turned me permanently and I thank God with all my heart for it. It was a tender, mysterious experience (that) influenced my soul down to its depths.”

After his conversion, Walter attended high school back in his second homeland of Germany, where he became fluent in German and often wrote letters home to his father in Latin and Greek. When he returned to Rochester, he was a mature young man — brilliant, serious and committed to finding where God wanted him to serve. Living at home, he attended the University of Rochester, then later the seminary where his father taught on the campus that was his boyhood playground. For two summers, he did what so many young ministry candidates have done — he served as the student pastor of a small Baptist congregation, one located in Kentucky. Later, upon graduating from the seminary, his concern for the lost almost took him to India as a foreign missionary.

A Harper’s Weekly cartoon of German emigrants boarding a steamer in Hamburg, Germany, 1874. (Wikipedia)

But as many of his biographers have commented, in 1886 Walter became another kind of missionary, as the 25-year-old pastor of the Second German Baptist Church in New York City, a small congregation located on the edge of a slum called “Hell’s Kitchen.” According to Evans, it was this $600-a-year ministry to 143 German working-class Baptists “that served as the greatest influence in shaping (Rauschenbusch’s) theology and his orientation toward social reform.”

William Ramsey explains the value of this experience, claiming:

Rauschenbusch’s social concern was not developed in his university study of Hegelian philosophy; it was prepared in the city. … He got to know women so underpaid in their factory jobs that they had to walk the streets every night as prostitutes. He told of an old man he knew who was hit by a streetcar. When the old man could not pay for his medical care, he was ejected from the nearby hospital and taken in the middle of the night by boat to a charity hospital (where he got gangrene and soon died). … The streetcar company settled with the wife for $100. After all, they said, (her husband) wasn’t earning much in the first place and was so old he wouldn’t even make that small amount much longer. … Hence, it was not from an ethics class that (the young minister’s) passion for social reform developed.

During seminary, Walter had thought that his Christian calling was to preach the gospel and bring individuals to salvation in Jesus Christ, but after living alongside the poor people of Hell’s Kitchen for 11 years, he felt that his call also required him to “minister to the victims of social indifference, political corruption and economic greed. It shook him that the slum landlords and sweatshop owners (he knew) were often sincere Christians, faithfully worshiping in fashionable churches while around them slum children were dying of malnutrition and the diseases poverty brings.”

Oddly, many rich Christians saw nothing incongruous about their comfortable lives in contrast to the pitiful existence of the poor. Some of them had no doubt read an 1889 book titled The Gospel of Wealth, published by industrialist Andrew Carnegie, in which he argued that God ordained some people to make lots of money and others not to fare so well. The rich were responsible for taking care of the poor, who didn’t know how to use money wisely anyway.

Oddly, many rich Christians saw nothing incongruous about their comfortable lives in contrast to the pitiful existence of the poor. Some of them had no doubt read an 1889 book titled The Gospel of Wealth, published by industrialist Andrew Carnegie, in which he argued that God ordained some people to make lots of money and others not to fare so well. The rich were responsible for taking care of the poor, who didn’t know how to use money wisely anyway.

Even more disastrously, notes historian Bill Leonard, it was a Baptist pastor, Russell Conwell, whose popular sermon “Acres of Diamonds” was responsible for justifying, even sanctifying, the materialistic desires of so many Protestant Christians in the late-19th century.

In his frequent appearances in conservative churches, Conwell declared: “Every good man ought to be rich. Every good man would be rich if he has as much common sense as goodness. I say, Get rich, get rich.”

Walter Rauschenbusch, like a number of other young, social-minded pastors and scholars, rejected this teaching, which he considered an aberration of the gospel and an accommodation to the culture of materialism and the laissez-faire capitalism of the Industrial Age. In response, Leonard notes, Walter emerged as “one of the chief representatives of what came to be known as the Social Gospel movement — an effort to take seriously the corporate nature of sin and the need to Christianize the social order itself.”

His first published exposition of this theology of social Christianity was a May 1904 article, ironically titled “The New Evangelism,” for even in this first outline of his Social Gospel ideas, Rauschenbusch could not forsake his inherent commitment to evangelism.

Thus, writes Evans: “He took aim at those who saw Christian evangelism merely as a matter of personal conversion. What was needed in the church … was a new model of evangelism that would bring persons in touch with the nation’s social and economic sins caused by late-19th-century industrialization.”

“He took aim at those who saw Christian evangelism merely as a matter of personal conversion.”

Rauschenbusch’s article was generally well received, but he wasn’t prepared for his ever-increasing visibility and stature. Just 14 years later, at the time of his death in 1918, he was the undisputed spokesperson for the Social Gospel movement. His books — Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907), Prayers of the Social Awakening (1910), Christianizing the Social Order (1912) and A Theology for the Social Gospel (1917) — had sold tens of thousands of copies in multiple printings. He had become, writes Evans, “one of the most visible Protestant leaders in the United States” who regularly crisscrossed the country speaking about the Social Gospel. His life and especially his ideas undergirded a movement that helped to shape the thought of Christian leaders in the early 20th century, while after his death the convictions he championed continued to challenge “numerous international church leaders and social reformers — most notably Martin Luther King, Jr.”

Further comments on the Social Gospel

The growing popularity of the Social Gospel in the early 20th century precipitated a reaction from more traditional Christian leaders and institutions. Commenting on Christianity in America, scholars from Harvard University’s Pluralism Project point to the growing antagonism toward this “new model of evangelism.” They summarize:

While theological conservatives drew upon traditions associated with revivalism, which tended to emphasize the moral reform of individuals, theological liberals called for a reconstruction of the social order itself. They insisted that Christians needed to address directly, and in Christian terms, the new realities of urban industrial life. … (They) found an articulate voice in Walter Rauschenbusch … (who) transformed the biblical idea of the kingdom of God into a vision of the progressive Christian transformation of America into a cooperative Christian society.

New York City children cooling off in a fire hydrant spray. (Date unknown)

Rauschenbusch’s vision of a ”cooperative Christian society” is radically different from the theocracy that some conservatives want to establish, where America’s laws would be made to agree with “God’s laws” as interpreted by conservative Christians. Conversely, the Social Gospel Rauschenbusch advocated imagined a social order where diverse voices should be heard, different perspectives could be respected and distinctive contributions to a transformed and just society would be welcomed.

This “liberal” understanding of the kingdom of God is still an anathema to conservative Christians today. A reaction to the Social Gospel I find particularly offensive comes from the website, Reformation Charlotte:

With the recent rise of progressive “Christianity” in the last few years, it’s no surprise that one of the prevailing themes is social justice, known colloquially as the “woke” movement. Many denominations have been caught up in the movement forever. But social justice is not the gospel, and saying that it is (the gospel) is heresy.

Walter Rauschenbusch was an American Baptist pastor and theologian who lived during the late 1800s and early 1900s. … (He) taught that the gospel’s primary consequence on earth is not the forgiveness of sins, but the solution to racism, social or economic inequality, poverty, crime, environmental problems or other social ills — hence, the heresy of Rauschenbuschism.

Yet, every time we repeat the Model Prayer that Jesus taught his disciples to pray, we are asking that the kingdom of God will come and the will of God shall be done on earth as it is in heaven (Matthew 6:10). In this prayer of the Lord, which some of us repeat every Sunday, is the petition that we — and by implication others — will have our hunger satisfied, debts forgiven, temptations avoided and evil enemies overcome (Matthew 6:11-13). This hunger, indebtedness, slavery to temptations or addictive behaviors and tyrannical oppression by circumstances, other persons or groups are the very kinds of social sins Rauschenbusch opposed and the victimization he observed and sought to confront.

“To follow the teachings and example of Jesus in seeking not only individual salvation but also social redemption is entirely consistent with the missionary impulse.”

While he was committed to individual salvation, Rauschenbucsh believed the death of Jesus was caused by collusion of sinful corporate forces. Referencing Walter’s thoughts from A Theology for the Social Gospel, Ramsey explains:

Rauschenbusch discussed in succession how each of the following sins contributed to Jesus’ death: religious bigotry, graft and political power, corruption of justice, mob spirit and mob action, militarism and class contempt. Jesus died fighting these, and his death is redemptive because it reveals those sins in all their horror, sets perfect love over against them and summons us now to the prophetic mission of working against them for the kingdom of God.

To follow the teachings and example of Jesus in seeking not only individual salvation but also social redemption is entirely consistent with the missionary impulse, and this faithful obedience fits appropriately with the concept of the missional church. I say this after serving 25 years as a cross-cultural missionary in Asia and later teaching missions for seminarians in the United States for two decades.

The missional church and the Social Gospel

In my experience, the Social Gospel connects with a theology of missions and the nature of the missional church in several ways. One correlation concerns the context in which we share our witness about Christ.

The Industrial Age of Rauschenbusch’s day was not all that different from the Information Age in which we live, perhaps most notably in the seemingly unscalable wall that separates the poor and the rich. A spirit of materialism, consumerism and laissez faire capitalism not only shaped the political choices and personal destinies of people then, but the same ethos is at work now.

Moreover, the religious warrants for being rich provided by Carnegie’s The Gospel of Wealth and Conwell’s Acres of Diamonds are mirrored in the contemporary health-and-wealth gospel so popular in our culture and in other parts of the world. These are all heretical interpretations of the gospel embodied and taught by Jesus — a poor man who lived among poor people, who gathered poor followers from among oppressed people to bring a message of good news to the poor.

A second link between the Social Gospel and the missional church is the motivation for doing missions.

Lindley notes that “some of the best-known leaders of the (Social Gospel) movement, like … Rauschenbusch, were awakened by personal contact with the devastating poverty of urban workers to a conviction that traditional charity was an insufficient solution to the needs of the poor.”

This awareness of human misery prompts many people to want to respond with compassion. What the Social Gospel encourages is the recognition that communicating good news requires our actions as well as our words, a teaching consistent with James 2:14-17: “What good is it, my brothers and sisters, if you say you have faith but do not have works? Can faith save you? If a brother or sister is naked and lacks daily food, and one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace; keep warm and eat your fill,’ and yet you do not supply their bodily needs, what is the good of that? So faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead.”

“What the Social Gospel encourages is the recognition that communicating good news requires our actions as well as our words.”

A third association of the missional church with the Social Gospel involves the holistic nature of the missionary task.

Rauschenbusch developed his views about the Social Gospel based upon an equally strong conviction that people needed to know Christ. Yet, he did not and could not believe that evangelism encompassed the whole mission of the church.

One day when praying, “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven,” it must have dawned upon Rauschenbusch that the kingdom of God was not only the central teaching of Jesus, but also the central missionary focus of the church. Thus, he wrote that faith in the kingdom of God “is not a matter of getting individuals to heaven, but of transforming the life on earth into the harmony of heaven.”

And for Rauschenbusch, transforming the lives of individuals on earth meant addressing every aspect of their lives — not just their spiritual selves. The great 20th century missionary and author Lesslie Newbigin concludes in his classic textbook on missions: “The prayer ‘Thy will be done (on earth as it is in heaven)’ is in vain if it is not made visible in action for the doing of that will. Consequently, (effective missionary strategies) have never been able to separate the preaching of the gospel from action for God’s justice.”

A final bridge between the Social Gospel and the missional church is the way in which the missionary witnesses.

James Scherer, a premier contemporary missions strategist, argues that one of the key issues for global missions in the 21st century is doing “mission in Christ’s way,” patterning our witness after “the self-emptying of the servant who lived among the people, sharing in their hopes and sufferings, giving his life on the cross for all humanity.”

Could it be that many conservative Christians regularly paint a powerful portrait of Jesus dying on the cross for humankind, but far too often add only the barest of sketches about his living alongside people in their pain and hopelessness?

Jesus faced dire circumstances, suffered alongside the poorest of the poor, rejected the value system of the world and lived as a person without material goods — vulnerable, humble, humiliated, “a man of sorrows acquainted with grief.” Yet, many Christians surprisingly reject this picture in favor of their view of a powerful, victorious (ultra-masculine) Jesus.

“Rauschenbusch’s understanding of how he must live if he followed a suffering Jesus was ridiculed.”

Rauschenbusch’s understanding of how he must live if he followed a suffering Jesus was ridiculed, also. As he labored in Hell’s Kitchen with uneducated and unimpressive day laborers, many of his middle-class friends from Uptown urged the highly educated and sophisticated Rauschenbusch “to give up his social work for ‘Christian work,’ (but) he believed his social work (was) Christ’s work,” according to Mark Galli and Ted Olsen.

Baptists have grown to love the 1835 hymn by Charlotte Elliot, “Just as I Am,” made famous through its use in thousands of revival meetings. Many might say that the words, “Just as I am, without one plea, but that thy blood was shed for me, and that thou bids me come to thee, O Lamb of God, I come” provide the clearest connection with the church’s central message and task.

But there’s another hymn our missional churches should be singing more often. It was written by Frank North, a New Yorker, who in 1905, under the influence of Rauschenbusch and the Social Gospel, penned the words to one of the clearest portraits ever written of Jesus, Where Cross the Crowded Ways of Life.

Where cross the crowded ways of life,

Where sound the cries of race and clan

Above the noise of selfish strife,

We hear your voice, O Son of man.

In haunts of wretchedness and need,

On shadowed thresholds dark with fears,

From paths where hide the lures of greed,

We catch the vision of your tears.

From tender childhood’s helplessness,

From woman’s grief, man’s burdened toil,

From famished souls, from sorrow’s stress,

Your heart has never known recoil.

O Master, from the mountainside

Make haste to heal these hearts of pain;

Among these restless throngs abide;

O tread the city’s streets again.

Till sons of men shall learn your love

And follow where your feet have trod,

Till, glorious from your heaven above,

Shall come the city of our God!

Maybe to sing Just as I Am so often is to perpetuate an incomplete, and hence not fully authentic, private gospel, whereas Jesus was so involved publicly. The Social Gospel isn’t anything other than the whole gospel, after all. It is the good news of the one who came to live among us, to share our sorrows and help carry our load, who gave himself for us and who calls us to do the very same for “the least of these,” his “little ones.”

So, I must ask: If individual believers and the church don’t live out the gospel socially, are they really embracing the true gospel at all?

Robert Sellers

Rob Sellers is professor of theology and missions emeritus at Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon Seminary in Abilene, Texas. He is a past chair of the board of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. He and his wife, Janie, served a quarter century as missionary teachers in Indonesia. They have two children and five grandchildren and now live in Waco, Texas.

Related articles:

Pastor seeks Southern Baptist resolution denouncing social justice

SBC leaders criticize Glenn Beck’s choice of words, but say he has a point