It’s not surprising that some Americans are willing to let Grandma die so that they can get more money. But it is surprising that they would tell Grandma that.

It’s not surprising that some Americans are willing to let Grandma die so that they can get more money. But it is surprising that they would tell Grandma that.

Nor is it stunning that while black and indigenous communities are ravaged by COVID-19, a handful of white people keep screaming that staying home to protect your neighbor is akin to tyranny. People of color are dying for the economy at horrific rates, yet somehow David Duke is now the new Rosa Parks. “Hands off my body,” these white people scream, irony nowhere to be seen, while at the same time attempting to use their autonomy to die for nothing.

“The racial caste system brutalizes black and other communities of color, while dangling just enough opportunity to white people to keep the system intact and to prevent most of us from revolting.”

Neither should it shock anyone that congressional Democrats keep playing the docile role of hognose snake. There’s a lot that ought not be risked right now, particularly the bodily health of millions of Americans. But there’s a lot that can be: the risk of better labor politics, for one, so as to prioritize the collective good of workers; or the risk of a sensible health care system, run for the purpose of actual care rather than some executive’s yacht payments; or even the risk of a financial response that puts the power of the federal purse in the pockets of people rather than in corporate coffers.

Instead, what ought to be an opposition party just curls back into the warm den they’ve built under Mitch McConnell’s thumb. The GOP tries to instill fear; the Democrats play it safe.

And no one – not a single person anywhere with breath still in their body – is astonished that the Trump administration is using a public health emergency to grab power. Passport issuance suspended. Immigration halted. Environmental rules gutted or abandoned. Federal piracy of Personal Protection Equipment. The list is too exhausting to think about. All of it is done in the name of power with neither checks nor balances, each step inching us closer to authoritarianism. The sophistication in using that power is sometimes questioned, but there is no doubt about the absolute determination to use power for evil.

Is this The American Dream?

Is this the “golden door” beside which Lady Liberty lifts her lamp?

Strangely enough, this thin conception of freedom has gained widespread acceptance, despite clear evidence that the libertarian impulses that hold much of the country’s political power do not work for the large majority. We are being called to die for an economy that only works for a handful of people. The racial caste system brutalizes black and other communities of color, while dangling just enough opportunity to white people to keep the system intact and to prevent most of us from revolting.

All of it is packaged with missionary zeal – “the greatest county in the world!” We export it around the globe, and we download it into our own souls without interrogating whether this is really life abundant.

All of it is packaged with missionary zeal – “the greatest county in the world!” We export it around the globe, and we download it into our own souls without interrogating whether this is really life abundant.

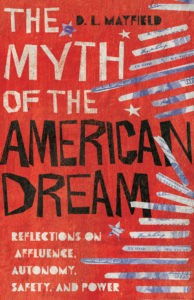

D.L. Mayfield has been thinking about the American dream, and the primary values enshrined in it. She names these as affluence, autonomy, safety and power. In The Myth of the American Dream: Reflections on Affluence, Autonomy, Safety and Power, recently released by InterVarsity Press, Mayfield sets out to interrogate both the cultural norms that have formed the structures of the American empire and ways she herself internalized those values. She demonstrates how narratives around affluence, autonomy, safety and power “lie beneath the surface of so many easy answers that both American culture and American evangelicalism have given to the problem of suffering in an unequal and unjust world.”

The confluence of American exceptionalism with a white evangelical culture that holds great political power has raised a theological specter. We are haunted by a merger of these two cultures. Together they restrict our society to perpetual immaturity, fixated on individual affluence over the common good, on personal autonomy over neighborhood wellness, on safety through arms rather than the pursuit of peace.

Thank God, Mayfield loves us enough to disturb us in a way that is patient and kind.

This book is not a polemic against white American evangelicalism. It is more a dispute among lovers, offered by one with all the bona fides. Chief among them: as a teen, she loved Jesus enough to start a Christian punk band. (That’s true devotion.) Her style has changed, but she remains passionate and committed, faithful to the tradition she grew up in. Because of that faithfulness, she keeps digging around, asking perceptive questions and looking for liberating stories.

Mayfield has a funny dose of humility, which she uses well to soften a subject that her fellow white evangelicals may not readily take to. “I am less a holy fool and more of an angst-ridden harbinger of doom,” she writes. Indeed, the book is at its best when she tries not to try to fix anything, but tells us stories about how she wound up at a banquet table that looks like the liberation Jesus preaches in his first sermon – good news for the poor, recovery of sight for the blind, release for captives, letting the oppressed go free.

“The moment is at hand for a different kind of mission, one carried on by exiles, by the oppressed, by those forgotten by the powers of this world.”

Over the course of 26 relatively short, interrelated essays, Mayfield looks around her Portland, Oregon, neighborhood. She invites us to look with her, to watch the little signs and wonders performed by the ordinary people she describes.

Those people, for the most part, are exiles. They have fled countries destabilized by political unrest, by more than a century of reckless, extractive U.S. foreign policy and by bad Christian missiology. In one of the Great Reversals common to the Gospels, those neighbors become missionaries. I dare to call them missionaries – despite the way Christianity has packaged the worst parts of the American Dream and offered it within supposedly “Good News” – because of how they testify to the love of God in the world.

The moment is at hand for a different kind of mission, one carried on by exiles, by the oppressed, by those forgotten by the powers of this world.

But they are not forgotten by God. While speaking to a group of student missionaries in training in 1968, the writer and priest Ivan Illich counseled the Americans embarking on short-term mission in Latin America to go home. They would be not just useless, but likely even harmful. “Perhaps,” he said, “this is the moment to instead bring home to the people of the U.S. the knowledge that the way of life they have chosen simply is not alive enough to be shared.”

That is the work before us now. Evangelizing the evangelicals. Demythologizing the empire. Deconstructing Pharaoh’s palace and his economy along with it. We will need stories and storytellers, poets and songwriters, artists and preachers, musicians and chefs and neighbors determined to love one another beautifully. The Myth of the American Dream invites readers into that kind of beauty.

Which sounds like Good News to me.

Read more BNG news and opinion related to the coronavirus pandemic:

#intimeslikethese