Mix sports fans, professional athletes, coaches, politics, race and social justice and you have a volatile concoction.

Several years ago, ESPN’s The Undefeated reported on a poll exploring the “racial divide” in the NFL. The poll measured attitudes of fans after San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the National Anthem. The poll consisted of responses from 5,630 fans. Fans and players were deeply divided on issues of race and how to talk about it.

The poll confirmed that white fans and Black fans talk about race in different ways. The language is English, but the rhetorical tropes are different. White people use an “underground” or in-house rhetoric of code words like “thugs,” “inner city” and “urban.” They are talking about race but not in explicit terms.

African American fans and white fans grow up in different worlds, different ways of talking about race. Black fans ask questions that often don’t occur to white fans. Why are all the owners white? Why are there only three Black head coaches? Why do sports journalists often speak of white players’ intelligence and Black players physical speed and agility?

“Black fans ask questions that often don’t occur to white fans.”

For example, there were multiple stories on ESPN and other sports shows about whether a white player could be an NFL cornerback or running back. This discussion came up when Stanford tailback Christian McCaffery was drafted eighth in the first round of the 2017 draft. McCaffery became the first white tailback drafted in the first round since Penn State’s John Cappelletti went 11th overall to the Los Angeles Rams in 1974. Racial stereotypes extend to positions that white players are capable of playing.

Exploring the social justice protests of athletes and coaches along with how white and Black fans discuss these issues, and how the NFL responded to the issue of race, opens a window into a better understanding of issues of race in America.

When athletes protest

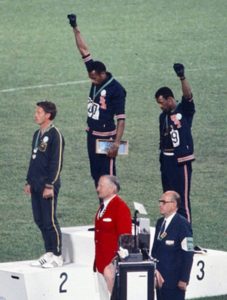

Gold medalist Tommie Smith (center) and bronze medalist John Carlos (right) showing the raised fist on the podium after the 200 m race at the 1968 Summer Olympics; both wear Olympic Project for Human Rights badges. Peter Norman (silver medalist, left) from Australia also wears an OPHR badge in solidarity with Smith and Carlos.

When an athlete of color violates a social and/or sporting norm of decorum, they face harsh repercussions. Famously, sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who bowed their heads and raised gloved fists during their medal ceremony at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, were labeled as “rude and disrespectful” and even received death threats for their breech of decorum. People assumed the medals platform at the Olympics was not a space for messages about race, religion, ethnicity or gender.

Athletes protesting racial injustice threaten American understandings of race. Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul Jabbar), Jackie Robinson, Muhammed Ali, Catfish Hunter, Billy Jean King and others were condemned for their activism. The anger erupts from a core understanding, a group of similar tropes: faith in America, white America, the American way of life, and America as a meritocracy.

Kaepernick’s anthem-kneeling protest against police brutality unleashed an avalanche of vitriol against him. This demonstrates the ongoing risk an athlete of color faces when engaging in even the most peaceful forms of ceremonial disruption. There’s something odd about “taking a knee” being seen as a sign of disrespect by a people as religious as most Americans.

Kaepernick’s protest during the National Anthem is the closest parallel to the act of Smith and Carlos. His implied message of police brutality introduced race-based injustices into the universe of American patriotism and the NFL brand. Kaepernick violated the understanding that the National Anthem, the flag and American militarism are sacred. His response to antiblack police brutality was smothered by a red, white and blue American flag larger than the one that flies over U.S. car dealer shops.

Curt Schilling watches the MLB game between the San Francisco Giants and Arizona Diamondbacks at Chase Field on August 3, 2018, in Phoenix. (Photo by Jennifer Stewart/Getty Images)

Politically conservative athletes also have been criticized and penalized for making political statements. Curt Schilling, Philadelphia Phillies pitcher, made a number of hard-right statements. He criticized the North Carolina transgender law. He assailed illegal immigrants. Schilling said Hillary Clinton “should be under a jail somewhere.” ESPN fired Schilling for his controversial remarks. As of this year, Schilling also has not been elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. His previous protests could be part of the reason for his exclusion.

Failure to support athletes

Former Baylor women’s basketball coach Kim Mulkey has faced criticism for not offering support to Brittney Griner as she sits in a Russian prison. Mulkey, now head coach of LSU Tigers women’s basketball, had been accused of racism and bigotry because Griner is African American and a lesbian. Jerry Brewer wrote an article titled “Kim Mulkey Owes Brittney Griner More than Contempt.”

Brewer says, “In all my years of covering the emotional, confrontational and sometimes crude world of sports, I’ve never encountered such a disturbingly bitter moment. … It’s reprehensible for a coach — a college coach who recruits teenagers with promises of familial relationships and lifelong bonds — to reject one of her own amid dire circumstances.”

Has Mulkey betrayed her former player because of a homophobic stance? Are conservative athletes wrongfully punished for making racist remarks? Are African American athletes prophets or punks when they speak out? Truth-tellers or thugs?

Who’s today’s truth-teller?

Randall Balmer has a new book, Passion Plays. In our email correspondence I shared with him my belief that historians have become more dependable “truth-tellers” than many theologians and preachers.

Balmer believes professional sports figures are now the locus of bold, prophetic truth-telling. The Greeks have a word for this act: parrhesia. The word means “free speech” and includes boldness, risks, danger and consequences.

“Now, as often as not, moral leadership emanates from the world of sports.”

Balmer said: “Americans once looked to religious leaders for truth, figures like Walter Rauschenbusch, Dorothy Day, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Malcolm X, Reinhold Niebuhr and Martin Luther King Jr. Now, as often as not, moral leadership emanates from the world of sports.”

In America sports have been “anointed” with religious power. Sports offer an escape, a this-world version of order as close to the Garden of Eden as conservatives can get. To protest in this idealized world comes across as being as deadly as Eve taking the first bite from the forbidden fruit. We will go to any length to avoid our eyes being opened and knowing we are naked.

Sports offers a land of nostalgia. It is the earthly version of the evangelical desire for a mythical America.

When fans protest athletes protesting

Fans and politicians opposed to player protests have devised a series of complex strategies to criticize the players. One is the insistence that athletes should play ball and not make statements, especially if those athletes are African American.

Related to that primal strategy is the idea that politics should play no role in sports. As a young preacher, I was told I should not preach about politics. Today, athletes are often told to stay out of politics.

In an essay titled “Race Talk, Fandom and the Legacy of Planation Culture in the NFL Player Protests,” Melissa A. Click, Amanda Edgar and Holly Holladay outline fans protesting political activism by African American athletes. They include a series of interviews with fans and note various responses from white fans who opposed protests by athletes.

One fan said. “Sports is a kind of entertainment industry. …. I don’t think an entertainment venue is the place for that.”

Presenting sports as a sacred space where certain topics are taboo helps cover the racism of the system. Some fans pointed out there was a time and a place for everything, even protesting at work, but they were offended by well-paid players protesting during the singing of the National Anthem.

The idea of sacred space underscores the depth of religious content in American sports.

Players of Iran wear jackets to cover up their country’s symbols in protest against the brutal repression of women in the Middle East country during the International Friendly between Senegal and Iran at Motion Invest Arena on September 27, 2022, in Maria Enzersdorf, Austria. (Photo by Robbie Jay Barratt – AMA/Getty Images)

Another strategy is the claim of colorblindness. In this view, football is a popular, colorblind passtime. It is entertainment. Football transcends politics. It is entertainment. Another fan in the survey says, “I don’t want to listen to a bunch of …. bitching and complaining about politics and sports. …. It doesn’t matter what color you are … everybody’s the same.” Ironically, the claim of colorblindness can be a cover for racism.

Yet another strategy is to claim football is not racist but is a meritocracy. The American dream at full speed in football. Competition, equal opportunity, family values, heroism, justice, manliness, toughness, strength and hard work. In one fan’s view: “The great thing about sports is that it was the same rules for everybody. It didn’t matter if you were rich or poor. Didn’t matter what your background was. Didn’t matter whether or not your nationality was one versus the other. …. It’s just, if you were good, you played, if you weren’t good, you could either give up or keep practicing and try out next year.” This suggests white fans have devised a way of talking about race without mentioning it.

Black fans have a different perspective. For example, an African American fan noted, “I get the people that say, ‘I go to sports to get away from all of it’ …. but one of the issues I have with those NFL people is that …. you have the privilege of being able to get away from it where, as a Black man, I don’t. It is always a part of my life.”

Some of the white respondents had an understanding of this situation. “I think white people …. are in denial and are uncomfortable discussing the privilege that they have and the fact that racism still exists because it’s just baked into everything,” one said.

“Protesters are perceived as disrupting the pleasure of white fans.”

Protesters are perceived as disrupting the pleasure of white fans. The desires of the fans become more important than players’ appeals for social justice. Is this an assertion that the property of whiteness includes the right to enjoy whiteness without the discomfort that Robin DiAngelo, in White Fragility, claims many white people often confuse with victimage?

One of the fans in the focus group said, “I think they forget that they’re employees and as an employer, if I say I expect you to do this and not do that and somebody violates that, they’re out of there. …. They’re paid to entertain us.”

Here the legacy of the plantation system casts a shadow over professional sports. Fans see themselves as “white plantation owners,” suggests Click, Edgar and Holladay, “with authority over what the players do while ‘on the job.’”

And not much imagination is required to see the NFL draft combine as a leftover of the plantation legacy as mostly Black bodies are measured, speed determined, along with agility and strength.

Another fan strategy is to insist that Black players should be grateful for the opportunities and salaries they receive. Playing professional football, from this perspective, is such a privilege. Some white fans imply that Black athletes aren’t really qualified to do much else other than play football. They should be grateful to get paid so much.

A closing word of hope

Despite these emotional arguments that return the legacy of systemic racism to our most cherished pastime, sports, I have confidence in the American ability to absorb social justice criticism and insert portions of those protests into our national moral fabric.

The long look suggests that protests against truth always have dogged us. Slavery didn’t end without a momentous struggle. Civil rights didn’t happen over a banquet at the White House, but included bombings of churches, fire hoses turned on Freedom Riders, imprisonment of marchers, police brutality and beatings, and the assassination of Martin Luther King. The right for women to vote created an uproar.

While some argue that change for the better happens in optimistic times, I am unconvinced that people in a good mood will voluntarily give up privilege and status for those deemed inferior without a fight.

The wheels of justice are greased by social justice protests. The long look of history will hash out the values Americans decide to embrace. Criticism and repercussions are a necessary part of that process.

I believe the social justice stances of courageous athletes, the parrhesiastes of our time, will at last be enshrined in the national memory as courage, boldness and truth.

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor in New York state and serves as a preaching instructor at Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump.

Related articles:

I’m standing with the kneelers. Will you join me? | Opinion by Russ Dean

Why aren’t we defending Brittney Griner? | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy

How Trump, Kaepernick and NFL inspire venom — and prophetic witness