Gallons of ink — physical and digital — have been spilled writing about the transformation of the Southern Baptist Convention at the hands of Paul Pressler and Paige Patterson. While they were, indeed, the architects of the “takeover” of the SBC or the “conservative resurgence” within the SBC, they are not the ones who carried the ball down the field for long-term transformation.

Among those soldiers in the practical implementation of the Southern Baptist Holy War, no single person has been more influential than Albert Mohler.

One of the reasons he has wielded such outsized influence is his staying power. Thirty years ago next week, he was elected the ninth president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, the historic flagship school of the SBC.

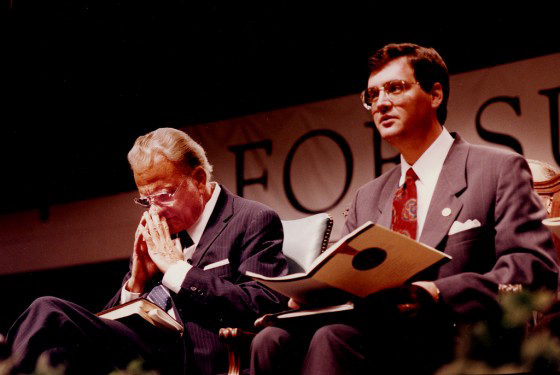

Al Mohler, the day of his election as seminary president in 1993, with Roy Honeycutt behind him.

His election on March 26, 1993, to succeed retiring President Roy Honeycutt sent shock waves through the alumni base and student body of the school that had been known for decades as one of the more progressive SBC seminaries. He was put in place by a trustee board that had just recently obtained a conservative supermajority because of the political plays of Patterson and Pressler.

Observers at the time knew the seminary was in for a change, but no one — not even the most hopeful supporters of the conservative movement — could have predicted how Mohler would transform the oldest of the SBC seminaries into the intellectual center of the movement and himself as its chief apologist.

Mohler is the longest-serving current head of an SBC agency or institution — by far — and the only current leader put in place during the tumultuous takeover period. All other SBC institutions have undergone multiple changes in leadership within the past three decades. By comparison, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary — once the SBC’s largest school — has had four presidents during the time Mohler has led Southern and currently is looking for the fifth.

Amid the ever-rolling chaos of SBC politics, Al Mohler abides.

Radical transformation

Mohler’s biography published on Southern Seminary’s website speaks of his leadership in sweeping terms, and that description is not wrong.

It says: “During Dr. Mohler’s tenure, the face of Southern has changed dramatically.”

And: “Dr. Mohler has presided over a remarkable transformation of Southern Seminary.

Both statements are uncontestably true.

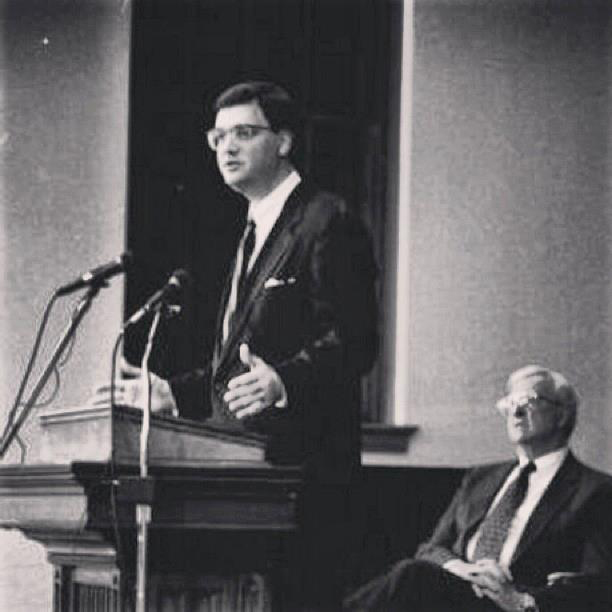

David Dockery (left) was dean of the School of Theology at Southern Seminary in Al Mohler’s first years there, then left to assume a university presidency. Today, Dockery is interim president at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

At the time of his election, at age 33, Mohler was not far removed from the seminary’s recent history. He had served as an assistant to Honeycutt and had been perceived by peers as agreeing with the school’s more progressive stances, including affirming women serving as pastors.

A common joke among Southern faculty and alumni at the time asked: “Do you know who would have been president at Southern if the moderates had won in the SBC?” The answer: Al Mohler.

Mohler was perceived as an opportunist who would have done or said anything to fulfill what he believed was his destiny — to lead the SBC’s oldest seminary.

Whether he changed his stripes or not, Mohler turned out to be a true believer. He carried water for the most conservative element within the SBC by giving an academic aura and intellectual rationale for their beliefs about the inerrancy of Scripture, complementarianism, the threats to the white Christian heritage in America and an absolute disdain for LGBTQ inclusion.

And like those who rallied the troops for political action in the “conservative resurgence,” he did so by appealing to the past. His stated intent was to return the seminary to the past and preserve its founding heritage — similar to the argument made by political conservatives in America who advance “originalism” and are obsessed by the “intent of the founders.”

Southern Seminary’s founding president, James P. Boyce, like the other founders, owned slaves.

On his 10th anniversary as president, Mohler explained: “We had a tradition to reclaim. That’s a very important gift God gave Southern Seminary. We wanted to claim that tradition of orthodox, classical Christian scholarship so deeply embedded in the Baptist tradition. Without apology, we believe that our students must know the word of God and in order, as the Apostle Paul said to Timothy, that they would rightly divide the word of truth and be workmen who need not be ashamed.”

That included a return to some cultural norms of the 19th century, especially as it pertains to the role of women. And it included a return to the Calvinism of some of Southern Seminary’s founders.

‘No girls allowed’

No one in SBC leadership has done more to quash the pastoral aspirations of women than Mohler. He has visited this theme early and often.

This was, in fact, the first major test he faced in his administration. Before his arrival, during the time conservatives held more sway on the trustee board but did not control it, Honeycutt had recommended several conservative faculty members in an attempt to achieve what conservative trustees demanded as “parity” on the faculty.

While passing as biblical inerrantists, these new faculty hires came from non-fundamentalist backgrounds, and most of them were unwilling to certify that God never would or could call a woman to serve as a pastor. Among the first casualties of the Mohler administration were not just old-time faculty members but several of these new hires who had passed muster with the conservative trustees but not with Mohler’s ultimatum on women.

Diana Garland

This dispute — combined with a Mohler ultimatum against LGBTQ Christians — came to a dramatic climax when he shut down the Carver School of Social Work rather than bow to the demands of the social work accrediting agency that required teaching students a more inclusive view of humanity. Mohler went head-to-head with Diana Garland, dean of the Carver School.

Garland refused to bend, and Mohler fired her. That was a shot heard around the world to signify how important the debates over gender and sexuality would be at Southern.

Over time, Mohler developed a closer relationship with the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, a group that advances strict complementarian theology. Mohler still serves on the group’s council, and CBMW board members and staff have been closely aligned with Southern Seminary and Mohler. The organization’s president, Denny Burk, serves as a professor of biblical studies at Southern’s Boyce College.

When CBMW was founded in 1987, it was seen as a fringe movement of far-right figures from the evangelical world. Thirty years later, it is fully integrated into SBC life largely due to Mohler’s influence.

Resurgent Calvinism

Mohler’s influence also is responsible for mainstreaming another once-fringe organization, Founders Ministries. This is a group of Southern Baptists who adhere to a historic theology known as Calvinism.

Calvinism as espoused by these neo-Calvinists is more strict and more severe than the form of Reformed theology taught by most Presbyterians in the United States. “Calvinism” and “Reformed” are used interchangeably, although Baptist and other evangelical adherents prefer the term “Reformed” and also label their theology “doctrines of grace.”

Again, Mohler and his allies believed turning the seminary to a full embrace of Reformed theology was returning it to a biblical past as evidenced in the school’s confessional statement, the Abstract of Principles, written by the seminary’s founding faculty members.

As a history of Founders Ministries explains: American evangelicalism “is sick and dying because it has abandoned its Calvinistic foundations. Our prescription for a cure is that our churches return to the old paths from whence they drifted. We have reasons to hope for a full recovery. In the first place, Calvinistic Christianity is nothing more and nothing less than biblical Christianity.”

Historically, Southern Baptists descend from a mixed stream on these doctrines. The history of Southern Seminary bears witness to this duality. One of its founders, who also became its first president, the Princeton-trained James Petigru Boyce, embraced Calvinism.

Even though Southern Baptists as a denomination had moved away from Calvinism and its teaching that some people are predestined by God for salvation while others are predestined for damnation, Founders Ministries — and Mohler — hoped to restore the old ways. Reformed theology, they argued, is “biblical” theology.

In 2001, Al Mohler presents Paige Patterson with the E.Y. Mullins Service Award.

Of all the changes Mohler brought to Southern Seminary, this is the one that caused the most friction with his otherwise loyal admirers. Teaching the doctrine of predestination ran headlong in to the great missionary impulses of modern-day Southern Baptists. How could SBC missionaries go out and preach that “God so loved the world” if they had been taught many of those people were headed to eternal torment and could do nothing to change that destiny?

This also pitted Mohler directly against one of the men who made his ascent possible, Paige Patterson. Patterson, who became president at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and then Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, is no Calvinist. Rather, he fully embraces the “whosever will may come” theology of Baptist revivalism.

“Patterson and Mohler agreed to work two sides of the same street and call it unity.”

Yet somehow, Patterson and Mohler agreed to work two sides of the same street and call it unity. While Patterson worked to put academic respectability on basic fundamentalist beliefs, Mohler and the faculty he assembled created intellectual and academic respectability for the “old-time” Reformed theology. They explained it in such a way as to be irresistible to those who sought a cut-and-dried theological framework to answer some of Christianity’s thorniest problems.

Passion conferences

Mohler’s rise to leadership within the SBC coincided with another youth movement that provided the perfect recruitment platform for a Southern Baptist Calvinist seminary — Louie Giglio and the Passion conferences.

Four years after Mohler took the helm at Southern Seminary, Giglio held his first Passion conference in Austin, Texas. That and subsequent events across the country drew thousands — and then tens of thousands — of college students to huge rallies featuring music and preaching.

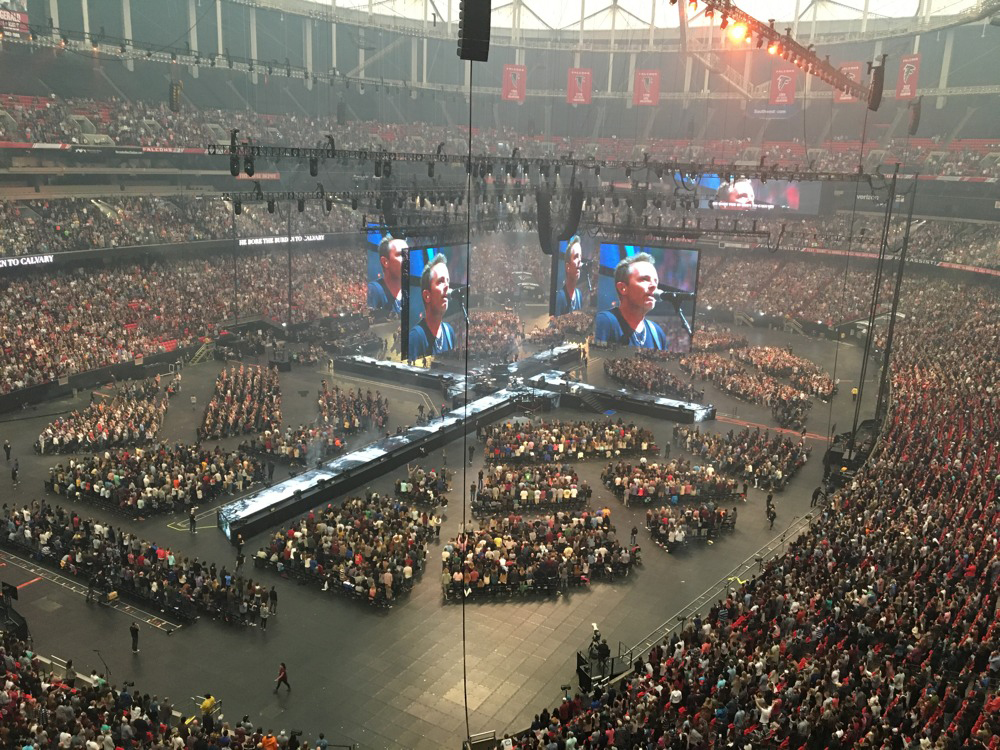

Passion 2017

There, many were introduced for the first time to Reformed theology as preached by guest speakers such as John Piper, one of the leading apologists for this doctrine among Baptists and other evangelicals in America.

Earlier this year, I had a conversation with a young former leader within the SBC who was educated at Southern Seminary and had been influenced by the Passion conferences as a college student. In fact, it was because of the Passion conferences that this person ended up at Southern.

The person telling this story recalled being in a meeting with about 30 young leaders in the SBC where it suddenly became apparent they all shared a connection through Louie Giglio. This person asked: “How many of you were at Passion in 1999?” Every hand in the room went up.

Either because of Passion or with confirmation from an experience at Passion, all these young Southern Baptist leaders had experienced a call to ministry and decided to go to seminary. It only took a little bit of research for these young, impressionable new Calvinists to realize they needed to get themselves to the SBC’s flagship seminary.

Building a farm team

Mohler’s influence at Southern, however, happened not just because he drew in students looking for certainty in answer to faith’s hardest questions. It’s because he exported a network of graduates and former faculty members across the SBC.

Many of the SBC’s key leaders today owe their positions to Mohler’s networking and influence.

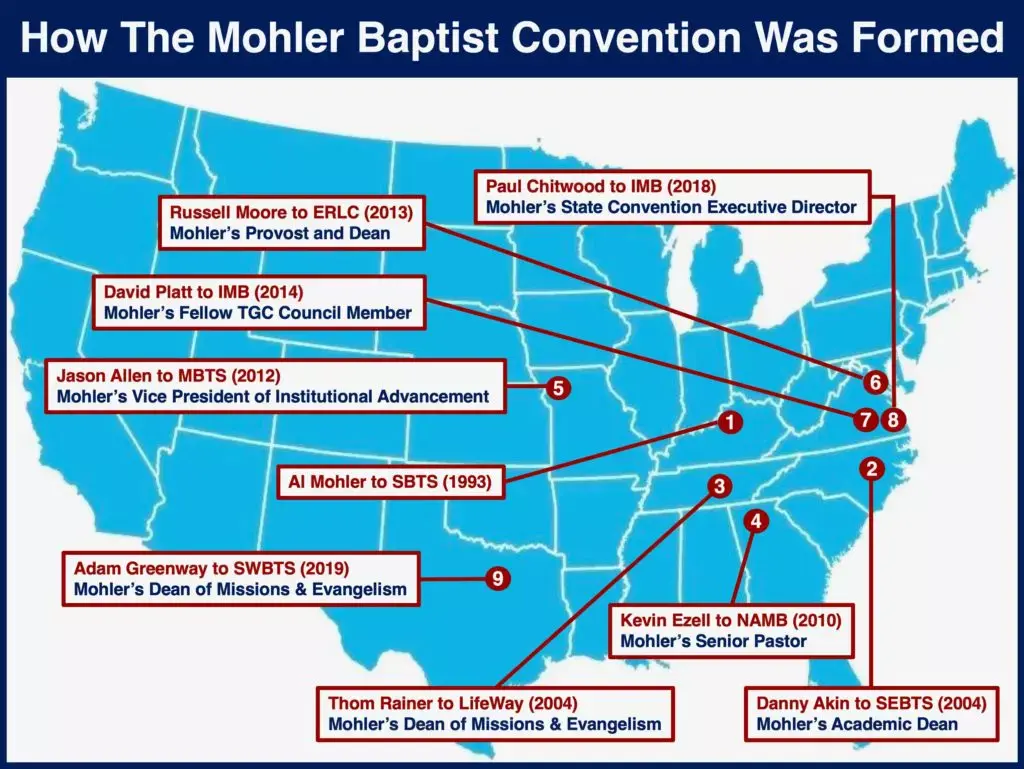

An organization critical of Mohler — because he’s not conservative enough — published a map showing some of Mohler’s far-flung influence. It includes eight SBC leaders who have direct ties to Mohler or served on his faculty.

An organization critical of Mohler — because he’s not conservative enough — published a map showing some of Mohler’s far-flung influence. It includes eight SBC leaders who have direct ties to Mohler or served on his faculty.

These include the current and immediate past presidents of the SBC’s International Mission Board, the current president of the SBC’s North American Mission Board, three seminary presidents, the former head of the SBC’s publishing ministry and — most notably — Russell Moore, former head of the SBC’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission and now editor in chief at Christianity Today.

Moore earned a Ph.D. in systematic theology from Southern Seminary under Mohler and then was hired to the faculty and soon after was named dean of the School of Theology. He is one of many young leaders who vaulted to prominence in the SBC under Mohler’s tutelage and sponsorship.

The very shape of the agencies these proteges have served also was influenced by Mohler, who served on the SBC task force appointed in 1995 to restructure the denomination’s agencies and institutions. Later, he served on the task force that updated the SBC’s doctrinal statement, the Baptist Faith and Message, in 2000.

Spokesperson in chief

Beyond the seminary’s Louisville campus, Mohler has deftly expanded his witness globally through social media and podcasting — and old-fashioned self-promotion.

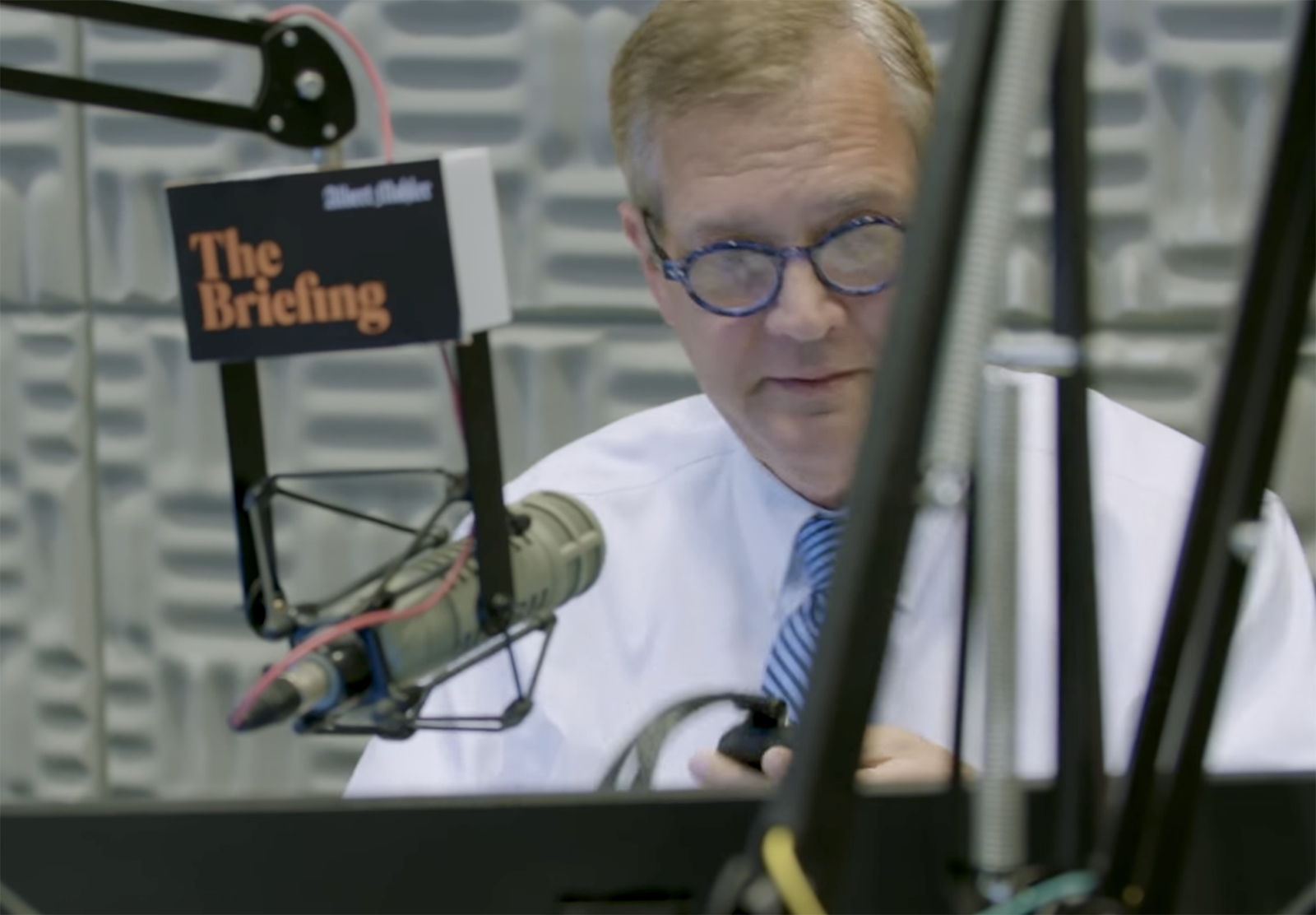

He built a physical broadcast studio on campus, where he records a daily podcast called The Briefing. He also carries a portable studio with him on road trips.

He built a physical broadcast studio on campus, where he records a daily podcast called The Briefing. He also carries a portable studio with him on road trips.

Equipped with technology and a supporting staff of interns adding to his research, Mohler has made himself a frequent guest on national TV and radio programs, as someone others turn to for commentary or explanation about world news or theological controversy.

He also serves as editor of WORLD Opinions, an editorial section of the conservative WORLD magazine.

Although not an official spokesman for the SBC, Mohler has become the most prominent and frequent commentator on Southern Baptist and evangelical issues, hands down. No one in the SBC is more visible and more quoted than Mohler.

After 30 years, he is his own brand.

Waning influence?

It was surprising, then, that when Mohler ran for the presidency of the Southern Baptist Convention in 2021, he didn’t even make the runoff. In the first round of balloting, he finished third in a four-way field.

How could this be?

The answer is complex and relates to the current generation of internecine warfare within the SBC. But the short answer is this: The SBC is shifting more to the right once again, and Mohler is perceived as not conservative enough.

The answer is complex and relates to the current generation of internecine warfare within the SBC. But the short answer is this: The SBC is shifting more to the right once again, and Mohler is perceived as not conservative enough.

He’s being out-Calvinisted and out-conservatived by the very people — and their successors — who made him.

Although he enthusiastically endorsed Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election, he had been a never-Trumper before. Ultra-conservatives in the SBC say he was too late to the game.

He tried to take a middle ground on the SBC’s controversy about Resolution 9 in 2019 — a resolution about the perceived threat of Critical Race Theory. Rightly acknowledging that an extreme form of this resolution would drive Black pastors from the SBC, Mohler nonetheless was labeled as “woke” by the fear-mongering right.

And then, there’s the reality of Ecclesiastes: To everything there is a season. Thirty years is a long time to hold such prominent influence in the nation’s largest non-Catholic denomination. Some of Mohler’s critics believe his influence is past its expiration date. He’s had his moment, made his mark, and it’s time to move on, they reason.

One other theory is that some of those SBC leaders who got their positions through Mohler’s kingmaking are now ready to be the kingmakers themselves. Chief among those is Kevin Ezell, current president of the North American Mission Board.

Kevin Ezell

Ezell’s first prominent position in the SBC happened when he was named pastor of Highview Baptist Church in Louisville, Ky., in 1996. Mohler was a member of the church at that time and had played a key role in firing the previous pastor, who was accused of having an affair. By most accounts, Mohler also was influential in Ezell’s election as pastor and then 14 years later his ascent to lead NAMB.

But Ezell has his own aspirations now. From his office in Alpharetta, Ga., the NAMB president controls millions of dollars in missions offerings he is using to demand loyalty from state conventions and their leaders.

To hear these state executives and missions leaders tell it, they are more afraid of Ezell today than of Mohler. Many of them also are more beholden to Ezell than to Mohler.

But the jury is out on whether Ezell’s kingmaking will survive. He’s increasingly being challenged by internal SBC critics and faces a potentially embarrassing trial this summer that could expose his behind-the scenes dealmaking.

At only 63 years of age, Mohler likely has several years of full-time work left in him. And he’s not yet the longest-serving president of Southern Seminary. That title currently goes to Duke McCall, who was president from 1951 to 1982.

It’s a safe bet that Al Mohler will abide at least two more years to beat that record. That would cement his place in history.

Mark Wingfield serves as executive director and publisher of Baptist News Global. In 1993, he served as news director of the Western Recorder, a weekly Baptist newspaper based in Louisville, Ky. In that capacity, he reported on the transition at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and was an eyewitness to the early years of the Mohler administration.