Owen Strachan woke up on Martin Luther King Jr. Day with decades of injustice weighing heavily on his mind: Men with long hair.

Strachan, who is former president of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood and is now provost and research professor of theology at Grace Bible Theological Seminary, tweeted, “Men: cut the man bun. Lop it off. Time to look like a man. No one wants to say this in an androgynous age, but in obedience to God, do it. No perfect length, but cut that hair down your back. And hand that Scrunchie back to your little sister. Look manly. God’s glory is in it!”

He added a screenshot of 1 Corinthians 11:14-15, which says that nature teaches it’s a disgrace for men to have long hair.

He added a screenshot of 1 Corinthians 11:14-15, which says that nature teaches it’s a disgrace for men to have long hair.

Like many evangelicals, the Theobros believe every sin must be punished at the Cross or in hell. So at what millimeter of hair length does God go from being totally fine to being so angry that either Jesus had to be crucified or someone must burn forever over it? And what kind of God needs glory by humans having certain haircuts?

The entire debate about hair length is absurd. And most Christians today understand that. Michael Bird, academic dean and lecturer in New Testament at Ridley College, responded: “Sweet Mother of Melchizedek, just how can Strachan say this nonsense with a straight face? It’s like he’s trying to impersonate John MacArthur and the Dos Equis Most Interesting Man … at the same time.”

After yet another head scratching controversy involving Strachan, Beth Moore, the Southern Baptist Bible teacher turned Anglican, tweeted: “Shoulda stuck with pony tails.”

In any case, this conversation ultimately isn’t about hair length. It’s about how we approach the Bible. It has massive implications for how we view inerrancy. And, despite our many differences, Strachan would agree with that.

Owen Strachan

He said as much when he doubled down the next day, tweeting, “Paul: long hair is a ‘disgrace’ for a man (1 Cor. 11:14). Do people still read, believe, and apply the Bible?”

Scientific inerrancy is about more than creation and the flood

According to the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, inerrantists “deny that biblical infallibility and inerrancy are limited to spiritual, religious or redemptive themes, exclusive of assertions in the fields of history and science,” and “deny that scientific hypotheses about earth history may properly be used to overturn the teaching of Scripture on creation and the flood.”

It would appear that inerrantists believe that whatever the Bible says in fields of science must be taken as completely true directly from the mouth of God.

When we think about science and the Bible, we tend to focus on creation and the flood, just as the Chicago Statement does. But there are many more science-related conversations in the Bible than those two issues. And when it comes to Paul’s teaching about nature and hair, there is a lot to untangle.

Does not nature itself teach?

This is not the first time Paul has made a statement about sexuality in its relationship to nature. In Romans 1:27, Paul says, “Even their women did change the natural use into that which is against nature.”

Likewise, in 1 Corinthians 11:14, Paul bases his prohibition of men having long hair on the teaching of nature.

“Sweet Mother of Melchizedek, just how can Strachan say this nonsense with a straight face?”

Apparently, Paul seems to have thought that nature reveals God’s will regarding gender-specific, sexuality-related behavior. But what if Paul was wrong about nature? If Paul’s premise were to fall apart, then wouldn’t his conclusions come into question as well?

Growing up in the complementarian world of independent Baptist fundamentalism, we were taught that boys and girls have distinct natures to them — where boys play with trucks while girls play with dolls, boys wear pants while girls wear dresses, and boys have short hair while girls have long hair.

But 21st century white evangelical gender stereotypes are not what Paul’s first century Corinthian readers had in mind when they read his letter. For us to understand Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians 11, we need to understand what Paul and his readers thought nature taught about hair. And if you’re tempted to pull your hair out over Strachan’s assumptions, just wait until you hear what Paul thought about it.

The context is corporate worship

Earlier in the passage, Paul says women who pray or prophecy during worship gatherings should either wear a veil or shave their heads.

In the Baptist world I grew up in, women were prohibited from praying or prophesying in church, yet also were not required to wear veils. Men, on the other hand, were prohibited from having long hair. We were told that Paul’s teaching about veils on women was cultural, while Paul’s teaching about long hair on men was universal. And we pretended he never said what he did about women praying and prophesying. I never quite understood how we could pick and choose what was cultural and what was universal.

Surely, there must be a way to make this passage gel more cohesively.

“If you’re tempted to pull your hair out over Strachan’s assumptions, just wait until you hear what Paul thought about it.”

While it may be difficult to cut through the confusion at this point about Paul’s line of reasoning and what we’re willing to obey, the context Paul was referring to was the gathering space for prayer and prophecy.

The ancient dualism of hair and testicles

Perhaps the most confusing part of 1 Corinthians 11:13-15 is that Paul says women’s hair must be covered when they pray, but also says that women have hair instead of a “covering.”

At first glance, this would appear to be a contradiction. But in a series of articles for the Journal of Biblical Literature spanning from 2004 to 2013, Troy Martin of St. Xavier University provided a wealth of primary sources from literature leading up to Paul’s day about the word “covering,” as well as about what they believed nature taught about hair.

Troy Martin

In Martin’s first article, he mentions that Euripides used Paul’s word for “covering” in a complaint by Hercules referring to his testicles.

Martin also shows how Achilles Tatius used Paul’s word for “covering” to mean testicles in his erotic story about Clitophon and Leucippe, specifically contrasting the sexual organs of female hair from male testicles.

Aristotle referred to the scrotum as “a shelter and a covering that protects the testicles,” again using the same word that Paul used.

So Martin concluded that the Greek word Paul used that gets translated into English as “covering” would have been read as “testicle” in its original cultural context.

Hippocrates on hair and semen storage

Martin notes that ancient medical professionals who followed Hippocrates, who is considered the “father of medicine” and whom the Hippocratic Oath is named after, taught that “hair is hollow and grows primarily from either male or female reproductive fluid or semen flowing into it and congealing (Hippocrates, Nat puer 20). Since hollow body parts create a vacuum and attract fluid, hair attracts semen. … Hair grows most prolifically from the head because the brain is the place where the semen is produced or at least stored” (Hippocrates, Genit. 1).

“Hair grows most prolifically from the head because the brain is the place where the semen is produced or at least stored.”

They were convinced that the reason babies and children have hair restricted mostly to their head prior to puberty was that “semen is stored in the brain and the channels of the body have not yet become large enough for reproductive fluid to travel throughout the body” (Hippocrates, Nat puer. 20; Genit. 2).

However, during puberty, Hippocrates and his followers taught that semen began moving from the brain down through the body. They also believed women’s bodies were colder, which prevented them from “frothing the semen throughout their bodies” (Hippocrates, Nat. puer. 20). In contrast, they believed men’s bodies were warmer, which allowed them to “froth this semen more readily throughout their whole bodies” (Hippocrates, Nat. puer. 20). Thus, women had less body hair, while men had more body hair.

The nature of a man

Hippocrates and Aristotle taught that men’s nature was to discharge semen and that when men and women have sex, the semen travels from men’s brains down to their genitals, filling all the body hair along the way.

Martin says that based on that understanding of nature, Hippocrates and Aristotle taught that “a man with long hair retains much or all of his semen, and his long hollow hair draws the semen toward his head area but away from his genital area, where it should be ejected.”

Hippocrates and Aristotle taught that “a man with long hair retains much or all of his semen, and his long hollow hair draws the semen toward his head area but away from his genital area, where it should be ejected.”

Therefore, Martin says, they concluded that testicles were weights that would counteract the suction power of the hair, “keep the seminal channels taut,” and draw the semen down so that the man could fulfill his nature of ejecting semen.

They believed nature taught that it was shameful for men to have long hair “since the male nature is to eject rather than retain semen.”

The nature of a woman

While ancient medical authors believed the nature of men was to eject semen, they believed women’s bodies were full of glands with the purpose of absorbing the semen and congealing it to make a baby.

Because they believed women’s hair draws the semen through its suction power, Pseudo Phocylides concluded, “Long hair is not fit for males, but for voluptuous women.”

Thus, for women, hair was seen as part of their genitalia. Martin notes that Hippocratic doctors tested to see if women were sterile by inserting “a scented suppository in a woman’s uterus” and then smelling her breath the next day to see if the scent had worked its way up her hollow body through the “suction power of her hair.” If the doctor could smell the suppository in her breath the next day, he concluded that her long hair’s suction power was working strongly enough to conceive.

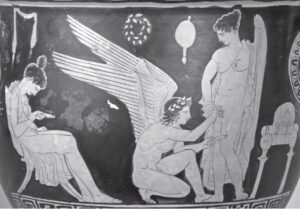

Art from 430—420 BCE, showing depilation of a woman’s genitals. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum.

During Paul’s day, women were so concerned with retaining their hair’s semen suction power that they singed their pubic hair to signal to men that the hair on their head had greater suction power than their pubic hair. Martin details how these women were celebrated in vase paintings and by authors such as Praxagora in Aristophanes’ Ecclesiazusae for singeing their pubic hair.

Additionally, Martin details how young girls prior to puberty “were not required to wear the veil” because “before puberty, a girl’s hair is not a functioning genital and does not differ from a boy’s hair.”

The church father Tertullian said to women, “Let her whose lower parts are not bare have her upper like-wise covered” and taught that the length of the veil should be “co-extensive with the space covered by the hair when unbound” (Virg. 17 [ANF 4:37])

After menopause, women were no longer encouraged to singe their pubic hair because their head hair was seen as no longer having its baby-making semen-suction power.

What was Paul thinking?

The reason Paul said women’s hair was their glory was that the medical professionals of his day taught that women’s hair helped them fulfill their nature. The reason Paul said it was a shame for men to have long hair was that the medical professionals of his day taught that long hair on men would prevent them from fulfilling their nature.

Because women’s hair was seen as connected to their genitalia, Paul required that women wear veils during corporate worship. To fail to cover genitalia during worship would have been seen as a violation of modesty in worship that was prioritized euphemistically in Isaiah 6:2 and literally in Exodus 20:26.

What do other scholars think?

According to the standard set in the Chicago Statement on Inerrancy, if you’re going to believe the Bible contains no scientific errors, then you’re going to have to accept Paul’s assumptions that hair has semen suction powers.

Assuming you’re not prepared to believe that about hair, you could pretend that when Paul talked about nature’s teaching on hair, he actually meant something completely different than what the medical professionals of his day taught.

“You could pretend that when Paul talked about nature’s teaching on hair, he actually meant something completely different than what the medical professionals of his day taught.”

You also could question Martin’s translation. Mark Goodacre of Duke University wasn’t convinced that Martin made the case for translating “covering” as “testicle.” But he admitted that “the interesting ancient medical data may shed light on the kinds of perspectives that Paul and his readers shared with respect to hair.”

Martin replied to Goodacre’s critique, showing how it was based on false assumptions about ancient Greek language and translation. And biblical scholar Michael Heiser said, “Especially in the last article when he addresses Goodacre’s concerns and criticisms, I think Martin eats Goodacre’s lunch.”

In an episode of the ironically named Naked Bible Podcast, Heiser concluded, “It’s just a great example of how you really can’t possibly understand the passage unless you have the first century person living in your head. … This just makes so much sense. It has high explanatory power for what’s going on here.”

Heiser built on Martin’s argument by showing that Paul’s reasoning in 1 Corinthians 11 also was based on how Jewish writers during the time of the second temple would have interpreted the sin of the angels in Genesis 6, when the angels were said to have sex with human women.

So you’re saying you know more than Paul?

Whenever one suggests that Paul might have been wrong about something, inerrantists will rhetorically ask, “So you’re saying you know more than Paul?”

A mosaic of the Apostle Paul from the 5th century CE in Ravenna, Italy.

In one sense, yes. We know more than Paul did about the nature of hair. We know that hair doesn’t have semen suction powers. Paul’s premise for his conclusion was undeniably wrong.

But in another sense, Paul’s primary concern was about something with which most if not all of us would agree. Paul was wrong about hair being genitalia. But even the most progressive amongst us would agree with Paul that it would be inappropriate for someone to expose their genitalia during public worship gatherings. So unless people are showing up to your local church naked, I wouldn’t worry about it.

Interpreting the Bible with humility

Inerrantists such as Strachan say the Bible is crystal clear. But when you begin untangling the cultural assumptions of the biblical authors, what may seem clear on the surface of a 21st century reading in an English translation might not be so cut and dry.

It’s understandable why many people who were trained to expect scientific inerrancy would look at Paul’s bizarre view of nature as a reason to question the authority of the Bible. It’s also understandable not to be too concerned since Paul’s conclusion about exposing your genitals in public was legitimate.

But whatever one believes about inerrancy or biblical authority, what is clear to me is that we need to take a more humble approach to biblical interpretation, and that we should be willing to learn from what archaeologists and biblical scholars uncover, especially when it comes to modern certainties about gender roles and sexuality that are based on ancient misunderstandings of nature.

Rick Pidcock is a freelance writer based in South Carolina. He is a former Clemons Fellow with BNG and recently completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com

Related articles:

Debate over women in Southern Baptist pulpits flares on social media

Prof terms stay-at-home dads ‘man fails’

Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood announces leadership change

Theologian says gender identity a ‘last wall’ in civilization