John Lewis spent his 21st birthday in a Nashville jail, Feb. 21, 1961. Lewis was arrested with 25 others after leading a public demonstration to gain admission to a whites-only movie theater. Several protesters, Lewis included, were students at American Baptist College; the movie was The Ten Commandments. Admission to the movie was refused; jail was not.

John Lewis, congressional representative from Georgia’s 5th District from 1987 to his death on July 17, 2020, recounts that experience in MARCH, a three-volume memoir, written with Andrew Aydin. The series, published in 2013, 2015 and 2016, documents events from the congressman’s Alabama sharecropper childhood to the signing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

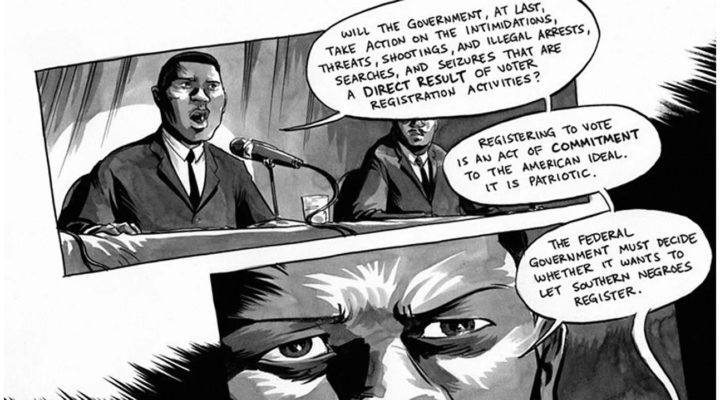

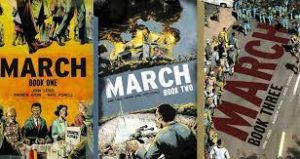

The books are a “graphic narrative” with events sketched out by Nate Powell. They detail Lewis’ engagement in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, surveying years of nonviolent protest against the legalized racism of Jim Crow, and the bombings, beatings, wanton imprisonments and murders perpetrated by those who wished to preserve it.

The books are a “graphic narrative” with events sketched out by Nate Powell. They detail Lewis’ engagement in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, surveying years of nonviolent protest against the legalized racism of Jim Crow, and the bombings, beatings, wanton imprisonments and murders perpetrated by those who wished to preserve it.

At age 18, Lewis met Martin Luther King Jr. and soon joined sit-ins to integrate Nashville lunch counters and other public spaces. He served as president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee from 1963 to 1966 and, in 1961, became one of the first 13 “Freedom Riders” endeavoring to desegregate interstate bus travel.

Lewis spoke at the 1963 March on Washington and spent much of his extraordinary life working to secure and preserve voting rights for all Americans. Such actions led to a near-death assault by Alabama law enforcement officers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965. MARCH is a powerful account of civil rights victories and setbacks on the way to desegregation and voter access.

If “legislated” integration was largely secured, voter access remains elusive.

On July 16, 2021, the day before the first anniversary of John Lewis’ death, I joined Brian Cole, Episcopal bishop of East Tennessee and a longtime friend, on a podcast to discuss MARCH as a resource for a diocesan group preparing for a civil rights pilgrimage to Selma and Montgomery. While MARCH is an important resource for understanding past struggles for racial freedom and voter registration, it also is a call to preserve those freedoms now.

On May 15, 1961, a bus bearing Freedom Riders leaves the station as they resumed their rides through the South in Montgomery, Ala. The Freedom Rides Movement of 1961 started in Washington, D.C. by 13 men and women who traveled to the South by bus and train to force desegregation of interstate transportation facilities. (AP Photo, File)

Sixty years after the Freedom Riders put their lives on the line against one set of culturally enforced racial injustices, other forms remain, as destructive in the feigned protection of “election security” in 2021 as segregationists were in 1961 with their blatant, volatile efforts to control the ballot box.

MARCH raised my consciousness of multiple national realities then and now. Here are three of them.

First, some new laws that limit voter access are hauntingly parallel to 60-year-old, blighted Jim Crow mandates.

This year, Georgia lawmakers apparently followed precedent set by law enforcement officers on Freedom Day, Oct. 7, 1963. in Dallas County, Ala., when large numbers of Black citizens lined up for voter registration — an opportunity available only on the first and third Mondays of each month. By noon, only 12 people had been registered, and the staff took a two-hour lunch break. The state trooper in charge warned those in line: “If any of y’all leaves that line for any reason — if you have to go to the bathroom, or you’re thirsty — any reason whatsoever — you’re not coming back, y’hear?!”

Activist Amelia Boynton implored the local sheriff: “Sheriff Clark, it doesn’t seem like a very Christian thing to let people drop dead on your courthouse steps.” Clark replied: “If they’re so thirsty, then they can get outta line and get something to drink. Ain’t nobody stopping ’em. But if I see any of you N***s trying to bring ’em anything — if I see you so much as talking to ’em, I’ll arrest you for molestin’ people trying to register to vote.”

When two SNCC staff members attempted to provide water, they were beaten by state troopers.

The 2021 Georgia law (SB 202) declares: “No person shall solicit votes in any manner or by any means or method, nor shall any person distribute or display any campaign material, nor shall any person give, offer to give, or participate in the giving of any money or gifts, including, but not limited to, food and drink, to an elector …”

Other elements of the law assure lengthened lines at polling places, especially in neighborhoods peopled by citizens of color. The Georgia legislation doesn’t use the militant language of the Alabama sheriff but retains a similar suppressive voting methodology.

“The Georgia legislation doesn’t use the militant language of the Alabama sheriff but retains a similar suppressive voting methodology.”

Second, John Lewis described numerous occasions when mob violence was leveled against civil rights protesters. Sixty years later, the Department of Homeland Security declares that “domestic violent extremism poses the most lethal, persistent terrorism-related threat to our homeland today.”

MARCH documents the way in which citizen “militias” and mob violence descended on civil rights activists — inflicting injury and death, often in collaboration with law enforcement. Lewis recalled Feb. 4, 1960, when a white preacher named Will Campbell warned protesters that if they initiated sit-ins, “local officials and the authorities will pull back. They will let police and … the rough element of the white community come in and beat you.” And they did. Demonstrators at Woolworth’s and other lunch counters gave no physical resistance when they were beaten by the mob. The experience transformed Lewis, who recalled, “I felt free, like I had crossed over.”

Image from “March” graphic novel.

On Jan. 6, 2021, a mob including white supremacists and Christian nationalists invaded the U.S. Capitol, seeking to overturn a national election. In her monumental work, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, Judith Butler wrote: “In a way, democratic theories have always feared ‘the mob’ even as they affirm the importance of expressions of the popular will, even in their unruly form.” She cites Alexis de Tocqueville, “who wondered quite explicitly whether democratic state structures could survive unbridled expressions of popular sovereignty or whether popular rule devolves into the tyranny of the majority.” (In our day, the tyranny of the minority.) Is more to come?

Third, MARCH details the years of struggle for justice and equal rights in a society seemingly incapable of escaping the legacy of slavery and segregation. Yet those horrendous and heroic stories may become unavailable to school children in many regions in the land of the free and the home of the censored classroom.

John Lewis’ own words, spoken on April 16, 1964, to the American Association of Newspaper Editors, capture the moment then and now: “Will the government, at last, take action in the intimidations, threats, shootings and illegal arrests, searches and seizures that are a direct result of voter registration activities? Registering to vote is an act of commitment to the American ideal. It is patriotic. The federal government must decide whether it wants to let Southern negroes register … or make us all witnesses to the lynching of democracy.”

“Registering to vote is an act of commitment to the American ideal. It is patriotic.”

In 2021, Representative Lewis’ assertions provoke an uneasy challenge for all Americans, young and old. Will his memoir of hard-won civil rights, and others like it, be available for instruction in the nation’s schools?

Will such books now be forbidden reading by Texas students, if and when authorities determine that John Lewis and his equal-rights-advocating-protester-colleagues believed that slavery, segregation, voting restrictions and Jim Crow culture were injustices more intricate to the American psyche than mere one-off “deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality” as Texas law now dictates? Or will Montana, Idaho or Oklahoma students be denied access to these illuminating volumes should state officials decide that they in any way “forced (students) to ‘reflect,’ ‘deconstruct,’ or ‘confront’ their racial identities?”

In 2021, are we yet a nation that restricts the right to vote, while restricting access to the legacy of those who gave their lives to secure it? Sixty decades later, is it time we “crossed over” with John Lewis, resisting the “lynching of democracy” in our own time?

Bill Leonard

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Critical Race Theory, voter suppression and historical negation: The irony of it all | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Voting rights and the ninth commandment | Analysis by Stephen Reeves

What I learned about voter suppression while sitting in the Quiet Chair as a child | Opinion by Paula Mangum Sheridan