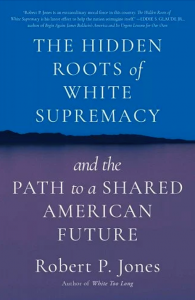

The historic fusing of Christianity and white supremacy is a moral and spiritual cancer eating at the body and soul of the American church, Robert P. Jones says in his latest book, The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path of a Shared American Future.

The book is scheduled for release Sept. 5.

A possible treatment for the condition lies in recognizing and confronting the central role of the 15th-century Doctrine of Discovery, a Vatican framework that cleared the way for white Europeans to explore and claim territories in the name of Christ, said Jones, president of Public Religion Research Institute and author of The End of White Christian America and White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity.

Robert P. Jones

“Christianity allowed itself to get wrapped up in idea that one of its key purposes was to be a justification of European domination of other people around the world,” he explained. “The church decided to lend its moral and religious authority to the project of colonial domination by Western European powers, setting the church on a disastrous course.”

One of those courses included the birth of a theology and worldview that inspired and rationalized the institution of slavery in the New World and the genocide and resettlement of Native Americans.

More than a condemnation of white Christianity, that history also contains its potential healing, Jones aid.

“If there is any hope that Christianity is going to find its way to health in this country, it’s only going to be by white Christian churches facing the root causes of its ill health, which includes its complicity in the idea that this entire continent was a divinely promised land for exploitation by European Christians — by white Christians.”

Jones said his latest project seeks to aid in healing by illuminating the troubled role of that ancient doctrine throughout U.S. history, including its resurgence in present-day Christian nationalism. “If we don’t trace white supremacy back that far, it means we have just worked around the edges of the illness,” he said.

The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy works in from those edges by delving into infamous incidents of Black oppression, including the 1955 murder of Emmett Till in Mississippi, the 1920 lynchings of three Black men in Duluth, Minn., and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in Oklahoma. But each is preceded by an in-depth history of the subjugation of indigenous people in the territories that became those states.

“We have to understand not only the story of Emmet Till, but we must also understand the Trail of Tears.”

“If we are going to understand white Christian identity, we have to understand not only the story of Emmet Till, but we must also understand the Trail of Tears. We can’t understand Tulsa without the story of the mistreatment, disenfranchisement and murder of Native Americans just down the road from Tulsa,” Jones said. “In order to tell the story more completely, I knew I was going to have to go beyond the Black-white story, as important as that is, because the story of slavery and Jim Crow and segregation need to be linked to the treatment of Native Americans.”

Jones said he leans into the disease metaphor to discuss white supremacy in the church because its symptoms are so obvious to observers. These include the continued declines in American religious affiliation and the ongoing membership freefall of the Southern Baptist Convention from 16.3 million in 2006 to 13.2 million last year.

“The signs of ill health are all around us,” he said. “Christianity in this country, and particularly white Christianity, is in a crisis moment and has been for some time. The symptoms of it now are undeniable.”

Pushback against such analysis usually comes from those who think the church is just fine and blame immigration, anti-racism efforts, LGBTQ and gender equality and a too-liberal application of religious liberty for the problems besetting their congregations. “But that’s like living with cancer and thinking cancer is normal, while in fact the disease is destroying your body,” he said.

“That’s like living with cancer and thinking cancer is normal, while in fact the disease is destroying your body.”

Jones’ latest book was written to help Christians diagnose the disease of white supremacy so they can take steps toward healing, he said. “When you realize that your body is not functioning the way it’s supposed to and you’re ill, you really do want to get to the bottom of it. You don’t want the doctor to just talk about the symptoms but to talk about and treat the cause.”

Jones said he comes at the critique from the perspective of someone who has suffered the illness of white supremacy himself. “I don’t see myself standing outside this tradition and wagging my finger at white Christians. This has been a long personal and painful journey I have been on.”

He documented part of that journey in White Too Long, in which he shares his discovery that his one-time denomination, the SBC, was founded in 1845 to provide biblical and theological cover for slave-owning Baptists. Another was learning of an ancestor who documented the slaves he owned in a family Bible.

He documented part of that journey in White Too Long, in which he shares his discovery that his one-time denomination, the SBC, was founded in 1845 to provide biblical and theological cover for slave-owning Baptists. Another was learning of an ancestor who documented the slaves he owned in a family Bible.

That discovery eventually inspired the writing of The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy, Jones explained. “I set about tracing that thread back as far as I could take it. It took me back to the beginning of the Colonial period and set the stage for the founding of the country — even before the founding of the country — to show how far back white supremacy has been entangled with Christianity. I wanted to look at what set us on this course and how we lost our way.”

But there are positive signs that belief in the divine sovereignty of white Christian America is being challenged, Jones said. “Groups like Christians Against Christian Nationalism give me hope, and there are a growing chorus of authors who look like me, who grew up in white churches, who are seeing and writing about these problems.”

Jones said since 2020 he has been invited to more than 100 churches desiring to have conversations about the issues he has raised in his books and other writings. “And these are overwhelmingly white churches who say we need to confront this problem. This includes many Baptist and Methodist congregations in places like Kentucky, Mississippi and Georgia and in the Midwest.

“I see this turning of the wheel. It’s slow. It’s episodic. It’s local. But I think it will lead to lasting change. These movements don’t always show up on the radar because they are not always as loud, but they are doing transformative work.”

Related article:

The call is coming from inside the house: White Christian churches as incubators of anti-democratic sentiment | Opinion by Robert P. Jones