“I recall a Sunday morning in the spring of 1968 when the pastor of the Southern Baptist Convention-related church in Mesquite, Texas, where I was youth minister, offered his sermonic response to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. It was a tragedy, he acknowledged, but since King’s methods and beliefs were terribly misguided, few should be surprised by events in Memphis. Amid those remarks, one of the youths seated near the front rose from his seat and walked out on the sermon. In my memory I can still hear his footsteps sounding above the preacher’s voice. Soon after that incident, the pastor called me to his office and denounced the young man’s action. Shaking his fist in my face, and using a racial epithet, he declared: ‘You’ve turned these youth into a bunch of n**** lovers.’ Fifty-four years later, even if his assertion was even the slightest bit correct, the preacher’s accusation remains one of the greatest complements I’ve ever received.”

Bill Leonard

That paragraph comes from a 2012 column in Associated Baptist Press, now Baptist News Global. The memory of that Texas Baptist Sunday overtook me while reading reports from the hate crimes trial of Georgians Gregory and Travis McMichael and their neighbor William Bryan, charged for their participation in the 2020 shooting of African American Ahmaud Arbery as he jogged through their neighborhood. Found guilty and sentenced to life in prison in an earlier murder trial, the three faced another jury on hate crime charges.

The Washington Post reported that on the first day of that trial an FBI intelligence analyst gave testimony “about investigators’ review of the defendants’ phone messages and social media. She spent most of her time on Travis McMichael, 36, walking the jury through a litany of conversations in which he denigrated Black people, often while calling them the n-word. McMichael associated Black people with criminality, spoke explicitly about committing violence against them and blamed them when he struggled to get a commercial driver’s license, accusing them of ‘running the show,’” at the licensing office.

While both trials produced guilty verdicts, the evidence from the hate crimes case became a horrific reminder that in spite of years of civil rights legislation, the abolition of Jim Crow segregationist policies, and the pending appointment of the first African American female to the U.S. Supreme Court, grassroots racism remains solidly ensconced in American society. The hate crimes verdict was handed down as bomb threats forced lockdowns and canceled classes at more than 20 Historic Black Colleges and Universities; school boards and state legislators set limits on the teaching content of American racial history; and the America First Political Action Conference, a white nationalist coalition, promoted its supremacy ideology at a Florida gathering aimed at young people.

Expansion of racial injustice

In her New York Times Feb. 24 editorial, “Racial Justice Isn’t Inevitable or Irrevocable,” Margaret Renkl writes: “It is easy for white people to recognize the expansion of racial justice when they see it but much harder to recognize the commensurate expansion of racial injustice that happens in response to every step forward: the unapologetic voter suppression, the systemic economic inequities, the escalating threats of violence. Many white people don’t want to acknowledge the three-steps-forward-two-steps-back nature of the fight for racial justice because it interferes with their conception of this country as a land of opportunity and as a nation that prizes human equality above all other values.”

“Legislation that sets boundaries for how race and racism are taught in American public education not only silences teachers; it silences history.”

Renkl’s assessment summarizes the efforts of multiple state legislators in passing laws that forbid or limit teaching Critical Race Theory, “a body of legal scholarship that is committed to the struggle against institutionalized racism within American society, by highlighting that racism has and is empowered through and by the legal system in this nation.”

Critical Race Theory is not taught in America’s K-12 schools and is primarily used in graduate legal studies. Yet it is being redefined and misinterpreted in school boards and curriculum committees across the country as Marxist, or as the ideology that “a particular sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color or national origin is inherently superior or inferior.”

Other recent laws set boundaries for classroom instruction related to the history of slavery, Jim Crow and other culture-based evidence of racial bigotry, often requiring that they be referenced only as anomalies in the American democratic ideal.

Legislation that sets boundaries for how race and racism are taught in American public education not only silences teachers; it silences history. In significant ways, these legislative boundaries serve to illustrate America’s continuing failure to confront the realities of racism past, present and future.

Trayvon and Ahmaud

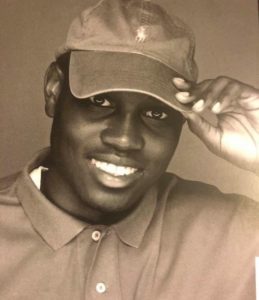

Trayvon Martin

Ahmaud Arbery

On Feb. 26, 2012, a 17-year-old African American Floridian named Trayvon Martin was shot down by “neighborhood watch captain” George Zimmerman, who found it suspicious that the Black, hoodie-clad youth was walking through a gated community (where he was visiting relatives). Ten years later, three Georgia vigilantes were found guilty of hate crimes in the murder of Ahmaud Abery, an African American they perceived suspicious as he jogged through their neighborhood.

Recounting those two events in a school classroom is not to suggest that students “bear responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex,” or to make students “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race,” as a recent Florida law offers as reasons for limiting curriculum on race and racism. It is an attempt to prevent other Trayvons or Ahmauds from being shot down in the next 10, 20, 30 years. Their deaths were not “committed in the past” but in our present.

What the church can do

All this isn’t simply about legislation and education. It also is about church. Much of the white church, especially in the South, was dragged kicking and screaming toward the Civil Rights movement by the Black church, as Martin Luther King’s 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and my Mesquite pastor’s 1968 racial epithet illustrate at either end of the ecclesiastical spectrum.

But this is 2022. Old racist attitudes and language remain, often with a life-threatening volatility like that of earlier generations. If state legislators and school boards are moving toward silencing or limiting how we teach our children about our sordid racial past, might churches renew our commitment to retell that history from inside the gospel?

“If state legislators and school boards are moving toward silencing or limiting how we teach our children about our sordid racial past, might churches renew our commitment to retell that history from inside the gospel?”

In White Too Long, PRRI’s Robert P. Jones writes that “the individualist theology that insists Christianity has little to say about social injustice — created to shield white consciences from the evils and continued legacy of slavery and segregation — lives on, not just in white evangelical churches, but also increasingly in white mainline and white Catholic churches as well.” This, he says, often puts white Christians “into the position of arguing that their religion and their God require them to aim lower than the highest human values of love, justice, equality and compassion.”

Trayvon, Ahmaud, and “a great cloud of witnesses” from slave shanties and lynching trees, lives snuffed out by racism, demand we break the pending silence, telling their stories in the name of one who still “takes away the sins of the world.” Failing to do so, we deserve to “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological (and gospel) distress.”

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Ahmaud, Breonna, Christian, George, and The Talk every black boy receives | Opinion by Timothy Peoples

No, justice was not done in convicting Ahmaud Arbery’s killers | Opinion by Susan Shaw