“Although a government may not promote or favor religion or coerce the consciences of students, schools also may not discriminate against private religious expression by students, teachers or other employees,” according to new guidance issued by the U.S. Department of Education May 15.

The official guidance is intended to clarify ongoing debates over what amount and what kinds of religious expression are legal in public school settings. It counters claims of religious conservatives that schools have become religion-free zones. And it counters claims of liberals that no religious expression should be allowed.

“Schools must also maintain neutrality among faiths rather than preferring one or more religions over others,” the federal guidance says, echoing decades of Supreme Court rulings and federal law.

The restatement of what’s allowable was sparked, in part, by the Supreme Court’s 2022 ruling in Kennedy v. Bremerton.

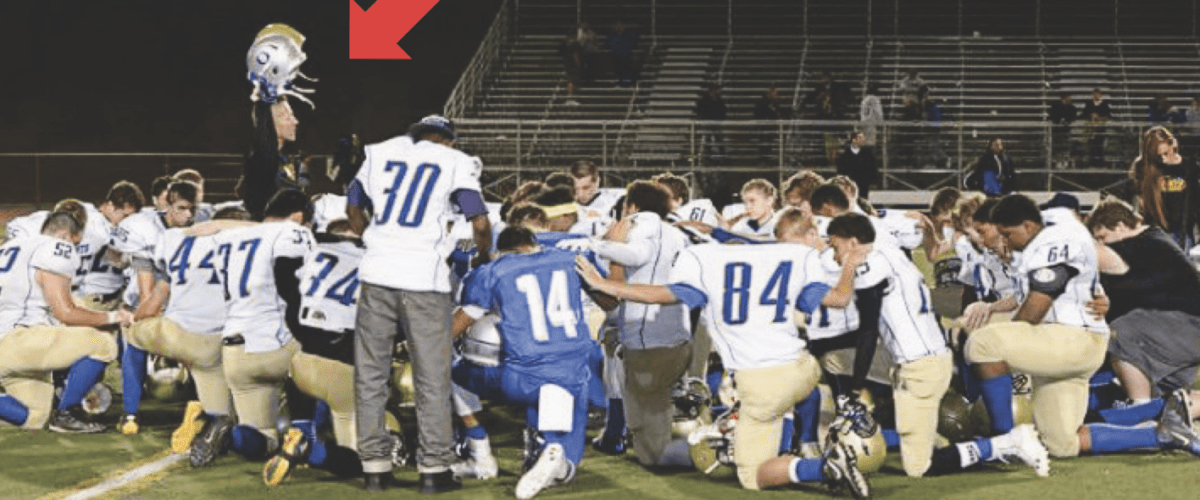

The restatement of what’s allowable was sparked, in part, by the Supreme Court’s 2022 ruling in Kennedy v. Bremerton, where a high school assistant football coach sought to hold public prayer gatherings on the 50-yard line after games. The court’s ruling in favor of the coach was narrow but also confusing, critics contend, because the court did not accurately state the nature of the prayers being led by the coach. What the court said was permissible and what the coach actually was doing are two different things.

The new guidance states: “A public school and its officials may not prescribe prayers to be recited by students or by school authorities. Indeed, it is ‘a cornerstone principle of (the U.S. Supreme Court’s) Establishment Clause jurisprudence that “it is no part of the business of government to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite as a part of a religious program carried on by government.”

On the other hand: “Nothing in the First Amendment, however, converts the public schools into religion-free zones or requires students, teachers or other school officials to leave their private religious expression behind at the schoolhouse door. The line between government-sponsored and privately initiated religious expression is vital to a proper understanding of what the Religion and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment prohibit and protect.”

The Supreme Court has ruled, the guidance says, there is a difference between “impermissible governmental religious speech” and “constitutionally protected private religious speech.”

In a direct reference to what Coach Joseph Kennedy sought to do in Bremerton, Wash., the guidance explains: “Teachers, coaches and other public school officials acting in their official capacities may not lead students in prayer, devotional readings or other religious activities, nor may they attempt to persuade or compel students to participate in prayer or other religious activities or to refrain from doing so.”

However, students and teachers do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” the guidance quotes from a court ruling.

For example, it quotes the court saying: “Nothing in the Constitution … prohibits any public school student from voluntarily praying at any time before, during or after the school day.”

Also, the guidance explains: “When teachers, coaches and other public school officials speak in their official capacities, they may not engage in prayer or promote religious views.”

Two traditional religious liberty watchdog groups applauded the federal guidance.

Holly Hollman

“The government should never tell students how, when or whether to pray. The U.S. Department of Education’s new guidance does a good job protecting students of all faiths and students who don’t practice a faith. It’s clear that the Biden administration understands the vital role that public schools play in ensuring faith freedom for all students,” said Holly Hollman, general counsel and associate executive director of BJC.

“While occasionally hard questions arise, most debates over legal and constitutional protections for religious expression in public schools have been settled for a long time,” she added. “The Biden administration’s guidance is in line with that from prior administrations from both parties, going back to the Clinton years. The Biden administration is correct to note that religious freedom protections were not altered by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton. While we were critical of the decision, the court’s approval of a coach’s private, brief prayer while his players were otherwise occupied should not be read as opening the door to more government-sponsored prayer in public schools.”

Rachel Laser

Likewise, Rachel Laser, president of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, commended the guidance: “We applaud the Biden administration for updating the guidance, which centers the religious freedom of public school students. As the administration reaffirms, public schools must be open and inclusive for students of every religion and none.

“Perhaps most importantly, the guidance emphasizes that public school employees, including teachers and coaches, may not coerce students to pray. Nothing about the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District changes the fact that the Constitution prohibits public schools from sponsoring prayer. This line has always been clear: Public school employees and officials cannot take advantage of their power and position to impose their personal religion on a captive audience of schoolchildren.”

Laser also had a sharp retort for “the Christian nationalist groups that pushed the Kennedy case are distorting the decision by arguing that public schools can now sponsor prayer.”

“The court’s conservative majority concluded that the coach could say a short, quiet, private prayer during his personal time and while his students were otherwise occupied,” she explained. “Even though this was a ‘deceitful narrative,’ the court based its ruling squarely on that fact pattern.”

Related articles:

There’s more to the praying coach story than reported, his attorney and publicist insist