If you find yourself confused by the phrase “zipper merge lane,” don’t worry, very few licensed drivers in my ZIP Code know what it means either.

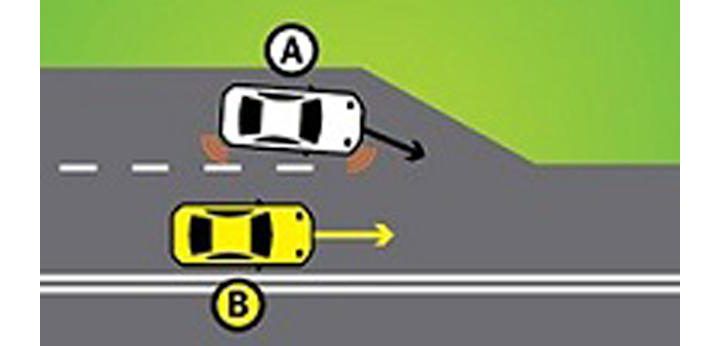

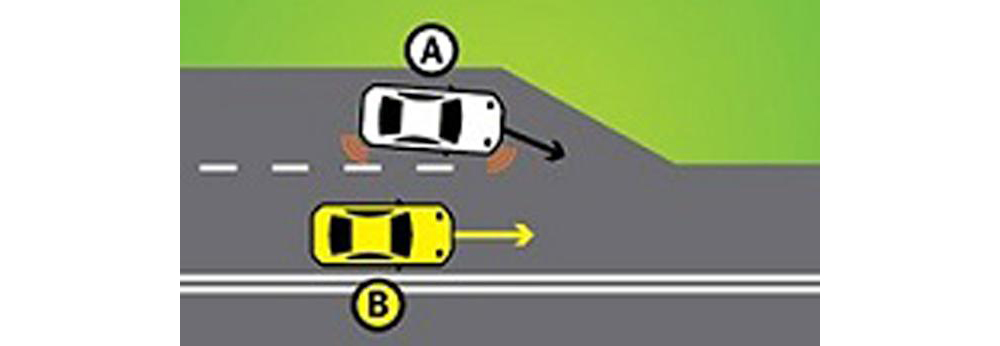

To clarify, imagine two lanes stretching several hundred feet in front of you before eventually merging into one. The zipper lane was engineered to provide extra space during exceedingly busy times in order to prevent traffic buildup from spilling back onto the interstate (like a ditch safely redirecting excess water during a flood). Ideally, it is supposed to be a helpful aid in reducing commute times and diminishing driver anxiety during particularly dangerous and accident-prone moments (like merging into heavy traffic during rush-hour).

Eric Minton

However, a weekly if not almost-daily feature of my commute, on days I return home from work around 5 p.m. or so, is the sight of 40 to 50 vehicles queued up behind one another in one lane to the point that cars are having difficulty exiting the interstate safely, while the other merge lane remains entirely empty. If anyone (myself included) tries to drive in the empty merge lane, other drivers in the crowded lane become passive or even openly aggressive in working to prevent those of us attempting to “zipper” from merging later when the two lanes become one.

A particularly funny (if not devastatingly sad) experience a family member of mine recently shared with me was the sight of an aggrieved driver, frustrated at seeing others “cut in front of them,” straddling the line between the main lane and the merge lane in an attempt to block drivers from getting around her unfairly. Think of it as a sit-in, but with a car in the middle of rush-hour. Her protest was undertaken during two light cycles in which she herself could have shortened her own commute by simply traveling forward in either lane rather than angrily parking in the middle of two lanes while drivers merged around her on both sides.

How we’re trained

In a July 2021 article for the New York Times on road rage, columnist Paul Stenquist described a zipper merge as “the best way to combine two busy lanes,” by creating a system where “drivers use both (merge) lanes until just before one ends, then merge like the teeth of a zipper coming together.”

“Perhaps if the zipper method were taught from a very early age and shown to be for the common good it might work. But otherwise don’t even think about squeezing in ahead of me.”

As his article continues, Stenquist describes the extent to which states have gone to enact laws mandating zippering as the preferred way of working to alleviate driver anxiety and road rage, only to encounter regular pushback from motorists, like Michigander Lane Aldrich, who commented that “Americans are fiercely protective of their property rights. They see someone who slides in at the last moment as a trespasser trying to steal something that is rightfully theirs. Perhaps if the zipper method were taught from a very early age and shown to be for the common good it might work. But otherwise don’t even think about squeezing in ahead of me.”

A similar “fiercely protective” mindset characterizes much of the backlash in some communities around student loan forgiveness, or increased access to mental and physical health care, child care, education, housing, or many other poverty-reduction measures enacted by federal, state or local governments that do not include some kind of “work requirement.” Not to mention the ways most of us have been taught to conceive of “laziness” and “entitlement” in every younger generational cohort complaining about what it takes to survive a situation the rest of us have just “learned to live with.”

Winner-take-all attitudes

My new friend Lane Aldrich is absolutely correct to name our uniquely American willingness to inconvenience, harm or even murder of fellow drivers in a road rage related incident as a kind of religiously (if not cellularly) maintained belief that all of us are getting screwed, so it’s best if we anxiously protect ourselves and violently request that others get off our lawn — or else.

He’s also right to attest, however, that if zipper merging could be “taught from a very early age and shown to be for the common good it might work.” I totally agree, Lane, it’s almost as if growing up in a winner-take-all society characterized by ballooning inequality, algorithmic standardization and loneliness closes us off to the collective pain of trying to be an American right now.

I know I myself have been hardened to the pain of my fellow Americans anytime I drive past the McDonald’s near my house and begin noticing the tops of brightly colored tarps providing shade to the unhoused community camping in the woods just behind the parking lot. Or whenever I casually write a check to Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee for health care they don’t cover because my deductible is unreachable, or when I regularly read that millions of Americans are bankrupted every year by a for-profit health care system that paid it’s 177 CEOs a combined $2.6 billion in 2018.

“Growing up in this country is like coming of age in the middle of a Black Friday sale where we are constantly in danger of being trampled upon.”

Growing up in this country is like coming of age in the middle of a Black Friday sale where we are constantly in danger of being trampled upon, stolen from, lied to, abandoned or overlooked because there are only 100 televisions or jobs or waffle irons or summer child care openings or scholarships or low-deductible health plans, or Playstations at the advertised sale price.

I’ve found that as an adult in my late 30s, it is impossible to make friends with my competitors, and it’s impossible to slow down and listen to the pain of those with whom I have been taught since birth to fear and fight with for increasingly scare opportunity. This is true even if these competitors are my neighbors or my own friends or even fellow workers grinding through another interminable commute.

Depressing, right?

It should be, which is why I believe so many of us Americans (1 in 3 of us at last count) are depressed and anxious and clinically lonely.

Seeing the common good

However, I’m convinced Lane Aldrich was on to something when he remarked that if, maybe, we could learn from a very early age that there is a common good, then somehow our generosity and openness to the pain of others — even during a crowded elevator ride or a traffic snarled afternoon — would strengthen, unite and save us rather than doing the opposite.

“Our willingness to see the grief, lamentation and pain of others as our own pain is a kind of political and emotional resistance.”

I’m saying our willingness to see the grief, lamentation and pain of others as our own pain is a kind of political and emotional resistance to a country desperate to abandon its duty to care for its citizens. Our pain in trying to survive in America is evidence not of individual moral failure or a warning of what can happen to us if we stop anxiously working, but as yet one more reminder that living in this kind of world harms all of us no matter how high our GDP rises.

As a family therapist I find it helpful to talk about the forces that raised us and taught us how to be a person in the world. I do so not out of some therapeutic commitment to telling folks their dads never loved them and consigning them to a grim future where all possibilities find themselves shunted because of a disordered attachment or an abusive childhood. I talk with people about what raised them in order to provide opportunities for what we call reparenting, which is a clinical way of describing a process of giving ourselves the kind of love and understanding we deserved much earlier in life in order to change the future rather than simply maligning the past.

As kids who grew up in this American family, it’s safe to say that scarcity and competition raised me, and it raised you. It’s time we stopped fighting among ourselves like siblings over the table scraps of what can only be described as an abusive and aloof parenting style, and it’s time we started empathizing, organizing and banding against this kind of parenting, together.

Eric Minton is a writer, pastor and therapist living with his family in Knoxville, Tenn. He holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Tennessee, a master of divinity degree from Fuller Theological Seminary and a master of science degree in clinical mental health counseling from Carson-Newman University.

Related articles:

A wish list for the common good in a new era | Opinion by Marv Knox

Hope for a new year out of the historical disunity of our United States | Opinion by David Jordan