There’s been a lot of talk recently about “vertical and horizontal morality.”

Most of these recent posts and conversations are from people trying to make sense of the recent election, trying to understand the differences between “conservative” and “liberal” perspectives. People are looking for a framework to understand why others see the world the way they do and why they vote the way they do.

Let me go ahead and say this: This isn’t a political article; I am not a politician. I do however study Christian ethics, so when people wander into my lane, into the field I have studied, researched and taught, I have to chime in.

There will be no further talk of the election, politics, parties or candidates. This is about Christian ethics.

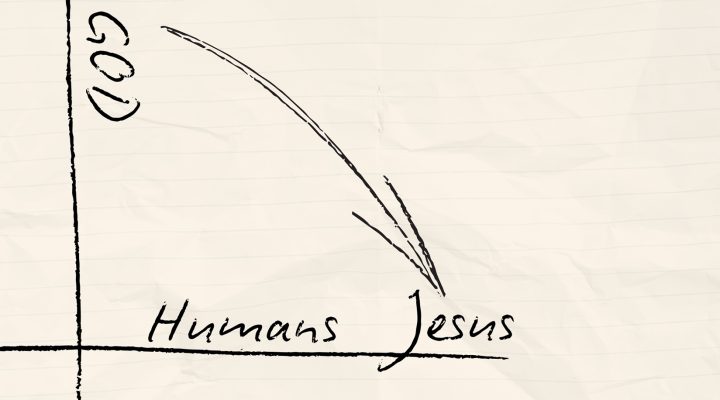

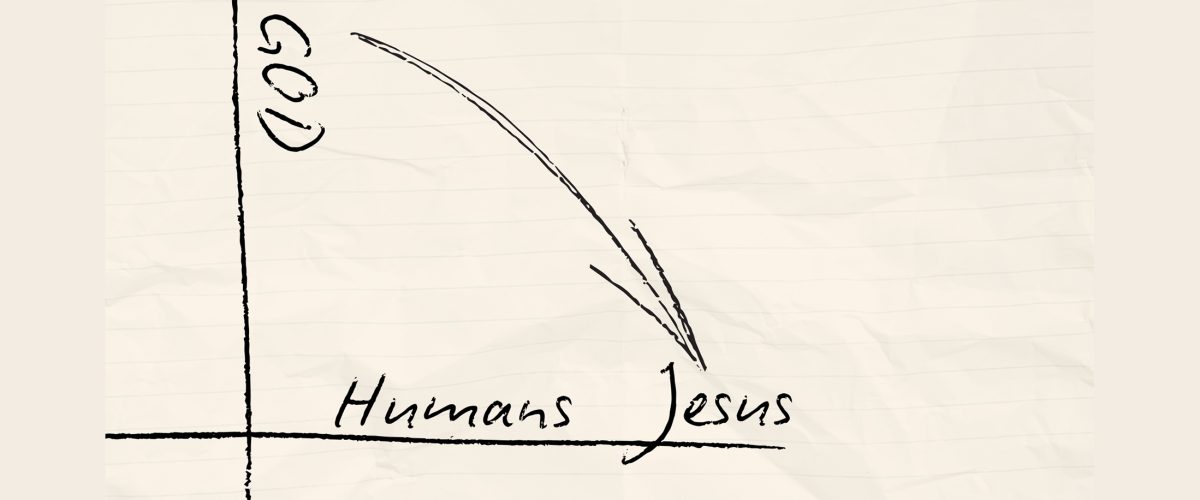

So, what are we talking about when we say “vertical” and “horizontal” morality? This is a deontological framework, meaning it helps us understand our ethical or moral duty in the world.

When we talk about “vertical” morality, we’re speaking to the duties and responsibilities we have to a higher power. It’s about the relationships that pull us upward, toward something greater than ourselves. It’s where we direct our attention, will and allegiance to something above us — a cause, an ideal, a nation, a leader, a tradition, our religion, our God. Vertical morality is the idea that we are compelled to live in response to something transcendent, something that exists outside and/or above us.

On the other hand, “horizontal” morality is about the duties and responsibilities we have to those around us. Horizontally, our focus is on our fellow humans, on our relationships with the people who are on the same level as we are. Here, our attention, will and allegiance are directed toward our peers, those who share the same space and plane of existence with us. In short, horizontal morality is about how we engage and relate to the people in our lives — our neighbors, our communities, outsiders.

These two directions of ethical responsibility — vertical and horizontal — often shape our decision making. We’re forced to ask ourselves: Which direction do we prioritize? Are we more motivated by our duty to something greater than us, or by our duty to those beside us?

“In the world of religion, particularly Christianity, people often lean heavily on the vertical aspect of morality.”

In the world of religion, particularly Christianity, people often lean heavily on the vertical aspect of morality. We talk a lot about our “relationship with God,” our “obedience to God’s commands” and our “faithfulness to God’s word.” The focus is on our responsibilities to God, and rightly so; our allegiance, worship, and obedience should be directed to God first.

For those outside the religious sphere, the primary moral relationship often is horizontal. Their obligations might be to people, to the environment, to the global community — to the “here and now.” The focus is less on allegiance to a higher power and more on responsibility to the tangible needs of others.

As Christians, which should take priority? Do we focus solely on our vertical duties to God, or should we also prioritize our horizontal relationships with others?

Enter Christmas.

The story of Christmas is, in itself, an answer to this question. In Jesus, we see the ultimate merging of the vertical and horizontal. God himself becomes human, and that changes everything.

This isn’t some distant deity looking down from the heavens, commanding obedience from afar. This is Emmanuel, God with us. This is God coming near, stepping into the messiness of human life, embracing the horizontal relationships that define our world. It’s scandalous. It’s unprecedented. It’s beautiful.

And it reshapes our understanding of ethics and duty in profound ways.

When God became human, God didn’t just confirm our vertical commitments; God reoriented them. When Jesus trades heaven for humanity, he brings the location of our vertical duties with him. In Jesus, our obligations to God now pass through our obligations to others. It’s no longer just about worshiping an abstract, untouchable deity.

“In Jesus, our vertical commitments are intertwined with our horizontal ones.”

In Jesus, our vertical commitments are intertwined with our horizontal ones. If we are to be obedient to God, that obedience flows through the way we interact with the people around us.

Consider Jesus’ own teachings. When asked about the greatest commandment, He didn’t stop with the ancient words of the Shema, reiterating the call to love God with all our heart, soul, mind and strength. He immediately added, “Love your neighbor as (you love) yourself” (Mark 12:30-31). It’s as though he’s saying, “You can’t love God without loving others.”

In his words and actions, Jesus redefines what it means to be faithful to God. Faithfulness to God now means serving, loving and caring for those around us.

Think about the passages in the New Testament where Jesus speaks about serving others and doing God’s will. In Matthew 25, he says when we feed the hungry, clothe the naked and visit the imprisoned, we’re actually doing these things for him. Our vertical duty to God is fulfilled by meeting the needs of others on the horizontal plane.

This isn’t a diminishment of our obligations to God; it’s an expansion of them. Jesus doesn’t lessen the importance of our vertical commitments; he gives them tangible expression through our horizontal relationships. In Christ, the vertical flows through the horizontal.

So, this Christmas, I encourage you to see the incarnation as an invitation. Emmanuel is an invitation to understand that our allegiance to God isn’t confined to Sunday mornings or personal piety. It’s lived out in our relationships, in our interactions with others and in our commitment to the well-being of our neighbors.

“Let the words of Philippians 2 set the tone for this Christmas season and beyond.”

Let the words of Philippians 2 set the tone for this Christmas season and beyond: “In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant.”

This is the mindset we’re called to have — a mindset that embraces humility, service and sacrificial love.

So, let Christmas be more than a celebration of God’s love for us. Let it be a reminder that our love for God must be shown through our love for others. Let this season challenge us to make God the center of our lives by connecting with those around us. In Jesus, God has come near, and now our worship and obedience are directed to him by loving our neighbor.

“Go and learn what this means! ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifices.’” — Jesus (Matthew 9:13)

Let’s live out our vertical commitments through the horizontal relationships God has placed in our lives. Let’s make room for Christ in the way we treat one another. Let our living sacrifice be shown in our pursuit of justice. And in the manger of Christmas, let us rediscover the God who was with us all along — and let that God change us.

Jeremy Hall serves as senior pastor of North Hills Community Baptist Church in Pittsburgh. He holds a doctor of ministry in justice and peacemaking from the McAfee School of Theology and co-hosts the Kingdom Ethics Podcast with David P. Gushee.