Veterans Day doesn’t lend itself to commercial attention like its twin, Memorial Day, probably because it’s squeezed between two other cash-registering holidays, Halloween and Thanksgiving, and it does not coincide with a car-cultural observance like the Indy 500 auto race.

But it is a federal holiday, what was originally called Armistice Day, marking the cessation of World War I hostilities on the 11th month of the 11th day at the 11th hour in 1918, although it took two decades after the war’s end for the day to be so marked.

In 1954, in the heat of the Cold War’s hysteria, when “God” became the mascot of the “free” world over against the “godless” communists, Armistice Day was repurposed by President Eisenhower as “Veterans Day.” In so doing, the work of mourning and incantations, resolving never-again, were displaced by the celebration of martial prowess.

British troops passing through the ruins of Ypres, West Flanders, Belgium, Sept. 29, 1918. (Encyclopædia Britannica)

The war, begun in July 1914, was supposed to be over by Christmas. And it was to be the “war to end all wars.” Instead, it escalated quickly. Given the imperial reach of several of the belligerent nations, soldiers from 28 countries participated. Nations as far away from Europe as South Africa and Japan participated.

It was unprecedented carnage. The first day alone of the Battle of the Somme resulted in more than 70,000 casualties. By war’s end, the final tally of vengeance for one assassination had claimed the lives of nearly 40 million combatants and civilians, many more wounded. Add to that, 8 million horses, mules and donkeys were killed.

I used to think the symbolic wearing of red poppies in remembrance of war’s sacrificial cost was a British thing. And mostly it is, if you include other nations who belong to the Commonwealth. It was a Canadian military surgeon, one with poetic inclinations, who established what is essentially a weed’s place in literary and military history.

Papaver rhoeas, known variously as the Flanders poppy, corn poppy, red poppy and corn rose.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.”

— John McCrae, “In Flanders Fields”

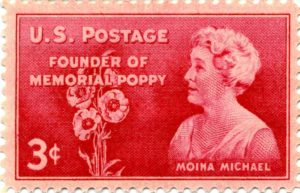

Story has it that Lt. Col. John McCrae was unhappy with his composition, written immediately after he presided over the 1915 battlefield burial of a close friend killed in the Second Battle of Ypres, Belgium; but some of his comrades retrieved the piece, which was published later that year. The story might have ended there had it not been for a literature professor at the University of Georgia, Moina Michael, who read “In Flanders Fields” in the Ladies Home Journal. She was so inspired that she successfully lobbied the American Legion Auxiliary to produce and sell silk red poppies to raise funds for supporting war veterans.

Moina Michael on a U.S. postage stamp. Michael first proposed using poppies as a symbol of remembrance.

At about the same time, a Frenchwoman named Anna Guérin also was championing the symbolic power of the red poppy as a cultural tradition supporting the war’s tragic memory. Eventually she convinced the Royal British Legion, whose mission was to support returning veterans, in adopting the practice. The observance in Britain took hold.

Writers as far back as the Napoleonic Wars noted the sudden appearance of the red poppy on battlefields. But it was McCrae’s grief-inspired poem that highlighted the association. That bit of verse led to the tradition of wearing artificial flowers resembling red poppies as a symbol of mournful remembrance of the war’s incalculable suffering, along with the resolve to never again commit such atrocities.

Armistice Day’s red poppy tradition, begun to finance the healing of war’s wounds, has been transposed into a patriotic call to arms. As has been said, war becomes perpetual when it is used as a rationale for peace.

Such sentiment is why novelist (and World War II veteran and prisoner of war) Kurt Vonnegut wrote, “Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans’ Day is not. So I will throw Veterans’ Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don’t want to throw away any sacred things.”

What we now know is that in soils like that of Flanders, a thin crust of alkaline is released when the ground is disturbed, as happens with bombardment and grave digging. The soil becomes acidic, choking most growth. But poppies thrive in such war-spoiled botanical conditions.

A volunteer constructs poppies at the Royal British Legion Poppy Factory, Richmond, Surrey, where 30 million poppies are made by a small team each year. (Wikimedia)

The red poppy is not a floral triumph. Rather, it is the ground’s tear, resulting from the soil’s hemorrhage. It is a prophetic judgment lodged against the despoiling of earth’s fertility — and against all mortal faith requiring blood sacrifice. As the Levitical writer warned, “If you defile the land, it will vomit you out.”

But blood calls out to blood. Lamech’s threat still holds: “If Cain is avenged sevenfold, truly Lamech (will avenge) seventy-sevenfold,” Violence has a built in escalator.

Indeed, the final lines of McCrae’s poem pointed in this vengeful direction.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow.

Who indeed can save us from this body of death?

P.S.: On Veterans Day, listen to this rendition of “Pie Jesu” (“Merciful Jesus”) by Sarah Brightman, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Paul Miles-Kingston. The music accompanies actual film footage from World War I’s “Battle of The Somme,” when French and British allies took the offensive against German troops in France, July 1 through Nov. 18, 1916. The British suffered 57,000 casualties on the first day of the offensive. All total, more than 1 million men were wounded or killed, making it one of the bloodiest battles in history.

Ken Sehested is curator of prayerandpolitiks.org, an online journal at the intersection of spiritual formation and prophetic action.

Related articles:

Care for veterans means supporting the living too | Opinion by Paula Mangum Sheridan and Marianne Hebert

62 years later, we learned the truth about Uncle Ray, a truth we needed to know | Opinion by Paula Mangum Sheridan