Connecting legislation with spirituality and supporters with tangible social justice actions propelled death penalty opponents to victory in Virginia, two organizers of the movement said during a March 29 Baptist News Global webinar.

LaKeisha Cook and Roberta Oster of the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy discussed the social media and grassroots organizing tactics employed to successfully overturn capital punishment in the commonwealth. The victory became official March 24 when Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam signed legislation making Virginia the 23d state — and the first in the South — to abolish state-sponsored executions.

Their webinar discussion, moderated by BNG Executive Director Mark Wingfield, offered guidance to anti-death penalty advocates in other states, dipped into the theology motivating opponents and supporters of capital punishment and suggested that the challenge of declining religious affiliation in the U.S. could in part be addressed by attracting younger generations with social action opportunities like those used to end state executions in Virginia.

“What we do is a possible draw for people coming back into religious institutions,” Cook, a Baptist minister and criminal justice reform organizer for the center, said after summarizing numerous surveys about Millennial and Generation Z attitudes toward faith and institutional religion.

“One of the main complaints young adults have about churches is that they don’t do social justice work.”

“One of the main complaints young adults have about churches is that they don’t do social justice work — they’re not concerned with what’s going on outside the church,” she said. “When they see churches committed to doing that type of work on a regular basis, it may be the Lord pulling people back in. I really do believe that the (abolition) work we did actually … helped pull people closer in again.”

LaKeisha Cook

In Virginia, that work began last fall when organizers saw the stars aligning for what looked like an especially promising legislative opportunity for abolition. Unlike previous attempts, bills were introduced in both the House and Senate, which are controlled by Democrats. And Northam was outspoken about his desire to see an end to the death penalty in the state.

“His support helped give even more momentum as we were going into the session,” Cook said.

A partnership began to emerge among death penalty opponents in the Commonwealth, including the Eighth Amendment Project, the Virginia Catholic Conference, the ACLU of Virginia and Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty.

The Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy launched a grassroots, multi-pronged campaign designed to remind legislators that the faith community was not letting up on its fervent support for abolition. Cook said she periodically contacted supporters to say, “We need you to email your legislator because this bill is moving into committee or is going up for a vote.”

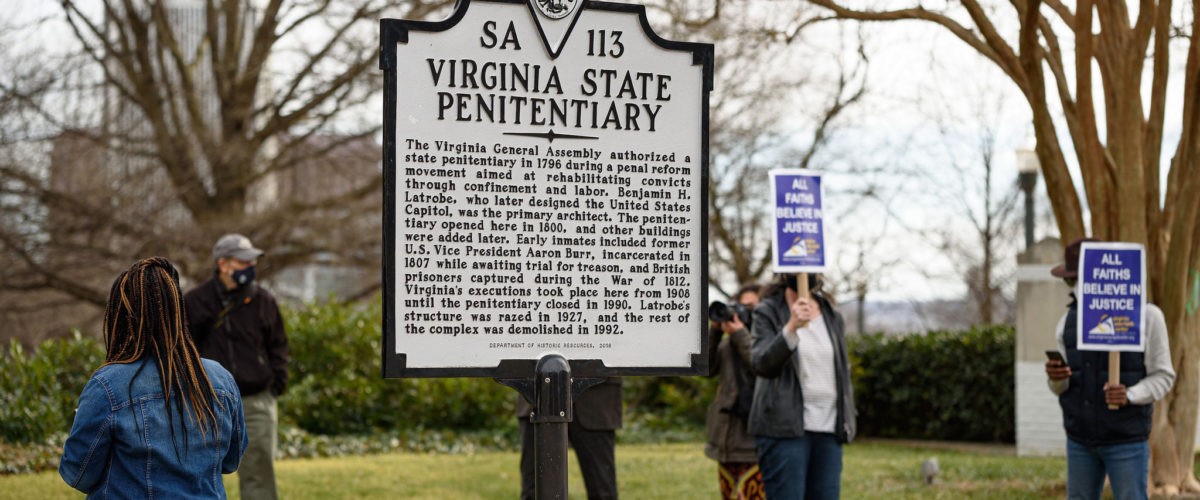

Black Christian clergy participated in a virtual press conference in January to highlight the state’s death penalty practice as an extension of lynching. Vigils were held statewide later in the month to symbolically and prayerfully connect the dots between slavery, the Jim Crow era and the modern-day practice of executing prisoners, who have been overwhelmingly Black.

A statewide, interfaith clergy petition drive added even more force to the movement and further expanded the spectrum of options laid before Virginians opposed to capital punishment.

Roberta Oster

“Those pieces were significant because they gave people something to participate in,” Cook said.

Oster, director of communications at the center, added that the effort included a social media piece and widespread media coverage that combined to work on intellectual and emotional levels. These components and events like the vigils “connected legislation with spirituality and, from a communications perspective, that was probably one of the most powerful tools to get the word out.”

Since the Virginia victory, the center has been advising abolitionist groups in other states on how to craft elements of their movements, Oster said. They also are in contact with advocates seeking to overturn federal capital punishment.

While details may vary, adopting the faith-based approach is one of the strongest suggestions they offer.

Having lay leaders and clergy from Bha’i, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Muslim and other traditions on board sent a powerful message to legislators, Oster said. “And we had a lot of Baptists.”

“I would advise any other state to look to the faith community” for support, she continued. “It’s powerful when you hear a preacher, especially an African American preacher, talk about this legacy of lynching and talk about injustice and the disproportionate number of African Americans who have been killed.”

She also suggested campaigns include endorsements from death row exonerees and the families of victims who can appear at events, on social media and to be available for media interviews.

“Teenage kids, college-age kids want that sense of fighting against injustice.”

“That strategy just resonates with people, and I would say to focus on young people as well. Teenage kids, college-age kids want that sense of fighting against injustice. They want to do something about a world that is falling apart, and this was a concrete way to actually pass a law that will stop the state from executing people.”

Death penalty opponents also should emphasize the possibility of executing innocent people, Cook said.

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, 170 death row inmates have been exonerated since the U.S. Supreme Court restored capital punishment in 1973.

“When the bill came up on the Senate floor and on the House floor, of course it was met with obvious opposition,” Cook said. “But what you never heard anybody try to argue against was the innocence argument. When you start talking to people about how many people have been exonerated on death row, there’s nothing they can say against that.”

While there was little pushback during the campaign from conservative religious groups, Cook said she is acutely aware of the theological differences between death penalty supporters and opponents.

“There are some religious groups, even some mainline denominations, that stand firmly behind capital punishment and believe that it is something that God mandates, and they’ll pull Scripture out to try to make that point.”

But faith-motivated abolitionists typically see God alone having the right and authority to take life. And the belief that God can redeem anyone, regardless of their crimes, also informed the campaign’s successful messaging, Cook said.

Oster said the principle played across religious traditions involved in the movement, including Judaism. “My rabbi would say the same thing. It is not up to us, it’s up to God. We are not God, so we have no right to take life.”

Watch the webinar here.

Related articles:

It’s official now: Death penalty no more in Virginia

Final vote sounds the death knell for capital punishment in Virginia

Virginia now one vote away from ending death penalty

The death penalty is dying a slow death; it’s time we pull the plug

Effort to end death penalty in Virginia gaining momentum; prayer vigils planned

New effort to repeal federal death penalty is beginning

Opposition to capital punishment reportedly growing among conservatives