Inside both the National Memorial for Peace and Justice visitor center and the Legacy Museum in downtown Montgomery, there is an installation composed of rows and rows of glass jars on wooden racks, containing soil samples from lynching sites. These samples were collected as part of Equal Justice Initiative’s Community Remembrance Project, which seeks to place historical markers at lynching sites, while bringing back soil to a central location as a tangible way of documenting and memorializing these victims of racial violence.

Robert P. Jones (Photo by Noah Willman)

The jars are labeled with the names, dates and locations of the victims in uniform white letters, which contrast with the different colors and textures of the soils. Some hold the sand of coastal regions, while others contain dark-black Delta cotton soil, the red clay of Alabama and Georgia, or the mossy loam of the low country. While these are contemporary soil samples that do not literally contain human remains from the lynchings, the way they bridge space and time is affecting.

Although I didn’t find any biblical references near the Community Remembrance Project exhibits, for those familiar with the Bible, the jars of soil powerfully evoke a story from the book of Genesis about the first set of brothers, Cain and Abel, born to Adam and Eve. In the ancient story, Cain becomes jealous of his younger brother, Abel, and, in a fit of anger, murders him in a field, far from the eyes of his parents. Afterward, God confronts a defiant and indignant Cain, who lies about the murder:

Now Cain talked with Abel his brother; and it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother and killed him. Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is Abel your brother?” He said, “I do not know. Am I my brother’s keeper?” The LORD said, “What have you done? Listen! Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground. Now you are under a curse and driven from the ground, which opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you work the ground, it will no longer yield its crops for you. You will be a restless wanderer on the earth.”

“I’ll be blunt: it is white Americans who have murdered our black and brown brothers and sisters.”

Notably, this story is “the mark of Cain” narrative that has served (in tandem with the “curse of Ham” story) as the most prominent theological justification of white supremacy. When Cain complains that his punishment is too harsh and that he will be killed if he is driven from his homeland, God agrees to mark him in some way as a visible sign of God’s protection, even while he remains under the curse. For generations, white Christians have interpreted this passage to describe the origins of dark-skinned humans, whom they understood as a race created not from the nobility of divine breath but from human acts of jealousy, murder and deception.

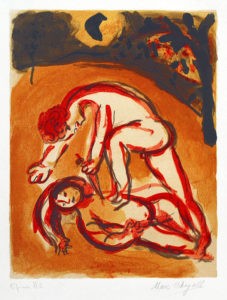

“Cain and Abel,” Frans Floris (public domain)

In the reflections of these glass jars of dirt dug from lynching site grounds, however, a different understanding materializes, one that inverts the traditional white interpretation of this story. I’ll be blunt: it is white Americans who have murdered our black and brown brothers and sisters. After the genocide and forced removal of Native Americans, the enslavement of millions of Africans, and the lynching of more than 4,400 of their surviving descendants, it is white Americans who have used our faith as a shield to justify our actions, deny our responsibility, and insist on our innocence. We, white Christian Americans, are Cain.

And despite our denials, equivocations, protests and excuses, as the biblical narrative declares, the soil itself preserves and carries a testimony of truth to God. Today God’s anguished questions — “Where is your brother?” and “What have you done?” — still hang in the air like morning mist on the Mississippi River. We are only just beginning to discern these questions, let alone find the words to voice honest answers.

These queries are, of course, rhetorical, even in the biblical story. God certainly knows the answers, and, if we’re honest with ourselves, so do we. I’ve always found it puzzling that God asks these questions of Cain. When I was younger, I thought perhaps God was playing a divine game of “gotcha” with Cain, laying a trap and testing him to see if he would lie.

But I think the better interpretation, and one that is relevant for us, is that God is giving Cain the opportunity for confession, for honesty, knowing that this would be the best path for Cain to begin reckoning with the traumatic experience of having killed his own brother, the pain he has unleashed for himself and others, and the consequences that will inevitably come. God’s questions were a compassionate invitation to Cain, giving him an opportunity to avoid the twisting of his personality that this trauma, and the perpetual deception required to cover it up, would inevitably bring.

“Cain and Abel,” Marc Chagall, 1960.

But just as we have, Cain doubles down. Throwing his own rhetorical question back at God — “Am I my brother’s keeper?” — Cain not only indignantly denies any knowledge of his brother’s fate but also rejects the very idea that he should be expected to answer God’s questions. Here, it’s clear that Cain’s decision to lie about his hand in the murder and to deny responsibility makes his future harder, just as our denials threaten our own future.

The challenge for white Americans today, and white Christians in particular, is whether and how we are going to answer these questions: “Where is your brother?” and “What have you done?”

As we contemplate our answers, there are certainly important pragmatic considerations. Continued racial inequality, injustice and unrest harm our ability to live together in a democratic society. Racial prejudice and divisions provide weapons for our enemies who wish to weaken us. White supremacy is sand in the gears of the economy and a source of life-threatening conflict in our communities.

But another important consideration, and one that we white Americans have given very little thought to, is the ways in which our complicity in this history, and our unwillingness to face it, have warped our own identities. Just as Cain was separated from his natural family, we have allowed white supremacy to separate us not just from our Black brothers and sisters but also from a true sense of who we are.

We are Cain. It is white Christian souls that have been most disfigured by the myth of white supremacy. And it is we who are most in need of repentance and restoration, not just for the sake of the descendants of those whom our ancestors kidnapped, robbed, whipped, murdered and oppressed; not just for those who today are unjustifiably shot by police, unfairly tried, wrongfully convicted, denied jobs and poorly educated in failing schools; but for the sake of our children and our own future.

And there’s hope here in the Genesis story. Even for the guilty and unrepentant Cain, God acts to preserve the possibility of a new future.

Robert P. Jones is CEO and founder of PRRI and a leading scholar and commentator on religion, culture and politics. This column is excerpted from his new book, WHITE TOO LONG: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity. Copyright © 2020 by Robert P. Jones. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Robert P. Jones is CEO and founder of PRRI and a leading scholar and commentator on religion, culture and politics. This column is excerpted from his new book, WHITE TOO LONG: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity. Copyright © 2020 by Robert P. Jones. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster Inc.