Why should we open our border to poor people from Central America? What if they are really terrorists? What if they have COVID, or something even more contagious? How can we afford to take care of “their” children when we can’t even take care of “our “own?

When I hear such questions, I have to fight back a real sense of disgust. Daily, we watch shattered refugee families tearfully sending their children to make their way alone in a foreign land in a desperate, last-ditch, effort at securing them a future. It takes a remarkable lack of empathy and compassion to see the crisis as theirs alone. It’s like a driver who feels horribly wronged when he has to sit through a green light because an ambulance is rushing a dying patient to an emergency room.

“It’s like a driver who feels horribly wronged when he has to sit through a green light because an ambulance is rushing a dying patient to an emergency room.”

I’ve been especially sickened listening to American politicians on both sides of the aisle blame each other for “our immigration crisis” without stopping to ask how we can save and protect so many frightened children in such need — children loved by God and made in God’s image.

I hear echoes of a much older, darker, voice. I hear Cain.

Chris Conley

“Am I my brother’s keeper?” Given how clearly Scripture answers, “yes,” I don’t think God would have been impressed with Cain’s question under any circumstances, but I wonder if Cain at least had the good sense to wipe Abel’s blood off his hands and clothes before asking it.

It doesn’t take much imagination to hear Cain’s question being repeated here and now in the context of our “immigration crisis,” especially if we reflect honestly on the United States’ shameful history in Central America — one that has left our own hands and clothes soaked in the blood of the innocent.

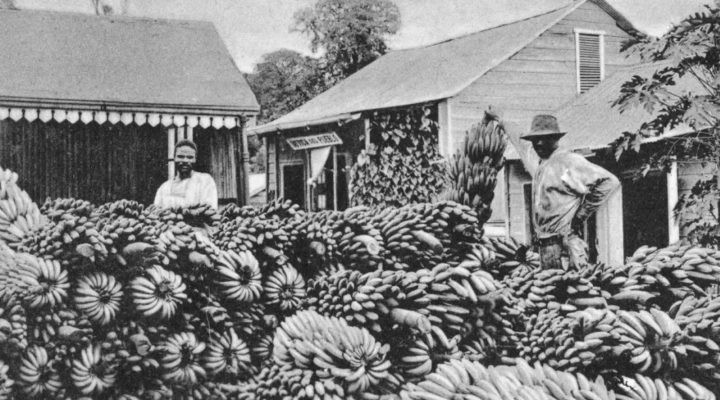

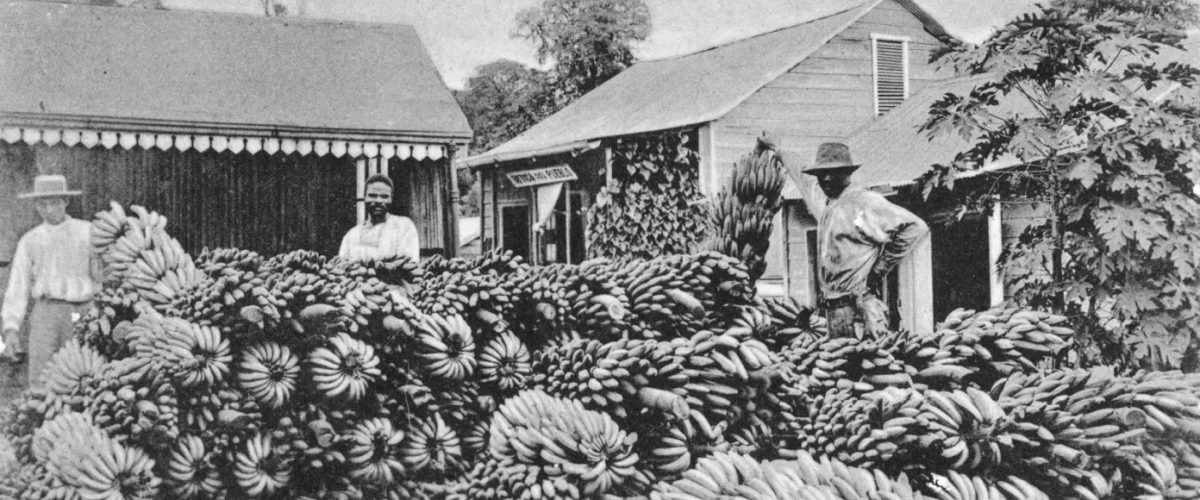

I think of Guatemala. For years leading up to the 1950s, Guatemalans had struggled against killing wealth inequality and poverty thanks largely to the United States looking out for what it perceived as its own best interests on foreign soil. As a result, while poor Guatemalans starved, an American corporation — the United Fruit Company — controlled much of the land and almost all of the wealth in Guatemala and staffed its massive plantations with Guatemalan peasants toiling in poverty. Native Guatemalans working the land of their own nation were ordered to always give the right of way to a “white man,” and to always remove their hats when speaking to one. It turns out Jim Crow can be exported.

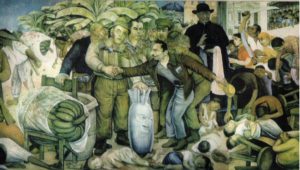

“Glorious Victory” is the sarcastic title of this painting by Mexican muralist Diego Rivera that shows Col. Carlos Castillo Armas greeting U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in a humiliating way, who is holding a bomb with the face of U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower and surrounded by banana stalks and dead children, next to whom is the U.S. ambassador, John Peurifoy, accompanied by several soldiers and the director of the CIA, who whispers in his brother’s ear, while on one side the archbishop of Guatemala, Mariano Rossell Arellano, is seen blessing the act, while the people of Guatemala protest.

Unsurprisingly, a majority of Guatemalan voters decided enough was enough, electing Jacob Arbenz Guzman as Guatemala’s president in 1951. Arbenz almost immediately enacted his “Decree 900” — a measure that would have, for the first time, made land ownership a reality for Guatemala’s suffering poor, and especially for its indigenous Mayan population, and would have ensured that Guatemalans could earn a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work. Raising the specter of communism, the CIA (urged on by the United Fruit Company) staged a political coup in 1954, removing a popularly elected Guatemalan president and replacing him with a brutal, pro-American, military dictator, and consigning the Guatemalan people to political turmoil and violence that would last decades.

For those of us losing our distance vision thanks to the aging process, however, we need not peer back as far as 1954 to see the Guatemalan blood dripping from our own hands and clothes as we look today’s Central American refugees in the face and dare to ask, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” All we need to do is focus on 1982.

The latest in a string of brutal military dictators to claw himself to power was Efrain Rios Montt, trained at the notorious School of the Americas in the Panama Canal Zone, whom President Reagan effusively praised as “a man of great personal integrity and commitment” — one whom Reagan claimed wanted “to improve the quality of life for all Guatemalans and to promote social justice.”

Now-declassified CIA correspondence indisputably shows that, even as Reagan was making this statement — and propping up Rios’ regime with weapons and training for his “death squads” — he was being told by his own intelligence community that there were mounting signs of “suspect right-wing violence,” with vast numbers of Guatemalan corpses “appearing in ditches and gullies.”

At the height of Rios’ blood-soaked, United States-supported, butchery, 3,000 civilians were “disappearing” (being murdered and buried in unmarked graves) per month. Guatemala collapsed into a full-scale, brutal civil war lasting until 1996.

Before a very tentative peace was reached, 45,000 civilian non-combatants had been “disappeared” by the Guatemalan government, almost 500 Mayan villages had been destroyed, 1 million Guatemalans had been turned into refugees, and more than 200,000 more Guatemalans were dead.

“United States-supported right-wing governments continued to engage in corruption that would make the mafia blush.”

These aren’t opinions. They are facts. Can you hear Cain yet? Can you see the blood on his hands and his clothes as he self-righteously asks whether he is his brother’s keeper? Can you see it on ours as we echo that question even today?

I’m old enough to remember the 1980s and the violence that engulfed Guatemala and much of Central America under the Reagan administration. You don’t have to be. Until the resignation of President Otto Perez Molina in 2015, United States-supported right-wing governments continued to engage in corruption that would make the mafia blush, and which continues to wreck the entire nation with poverty, crime and death.

Just as a snapshot glimpse, the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala determined that a shocking 95% of the far-too-common murders committed in Guatemala in 2006 never were solved. The ghosts of the dead still haunt Guatemala. The people understandably flee.

As a lawyer, I can confidently proclaim that the law is a remarkably odd thing, especially until you are disabused of the notion that law, justice and morality are synonyms. Early in law school, I was shocked to learn that I had no legal duty to save a man drowning in a pool, even if I could do so easily and at no risk to myself. Cain-like, it turns out that often in the eyes of the law, you are not your brother’s keeper. Unless you are the one who threw the man into the pool in the first place.

“We cannot now close our border to those fleeing the horror we helped create.”

Then, even the law would look at your bloody hands and clothes and declare that, by your guilt, you have been made your brother’s keeper. Having harmed, you must save. Even in this crabbed sense of “duty,” having ignored our own border to make Central America unlivable for so many of its native sons and daughters in the name of the “best interests of the United States,” we cannot now close our border to those fleeing the horror we helped create.

How much more so when we look not through the lens of law, but with eyes of faith? From that view, even without an understanding of the unsavory role played by America for decades in Central America in deliberately destabilizing an entire region with deadly consequences in the name of American corporate profits and anti-communism, we have a moral obligation to the “least of these among us” — to those fleeing crushing poverty and violence to find a better way of life for themselves and their children in America.

If Christ is truly not simply with, but in, the poor stranger — and I believe he is — it is time for disgusting questions to stop, and for love and welcome to start. In that sense, maybe this is our crisis after all.

Chris Conley is an attorney and graduate of the University of Georgia and of the Emory University School of Law. He and his wife, Mary, live in Athens, Ga., where both are members and deacons at First Baptist Church. They have one son, Aaron, who also is an attorney, and a miniature schnauzer, Oso, whose career path remains uncertain.