There was great fanfare over the decision by Congress earlier this month to establish Juneteenth as a federal holiday. The president acknowledged that it was long overdue (and indeed, it was).

But many within the Black community lamented that the move was a symbol without substance; and as we approach the annual July 4th celebrations of America’s so-called “Independence Day,” that yawning gap between symbol and substance will be in sharp relief.

Paul Robeson Ford

Much of the lament was focused on the fact that while Congress went to great parliamentary lengths to put Juneteenth on the books as a federal holiday, Congress has proved incapable of passing either of the two voting rights bills (For the People Act and the John Lewis bill) that have been before it for months now.

But July 4th presents us with an inconsistency that could be much simpler — (sarcastic) wink, wink — to resolve: Why are we celebrating two independence days in the same year, in fact, in the same 30 day period, in the same country?

This is where the reason for the symbol-without-substance quagmire becomes clear: We’re still struggling to figure out what unites us. No Congressperson in their right mind would have injected this question into the debate over Juneteenth because of the risk that it would have derailed smooth passage and turned that motion into the type of fight Congress once endured over the effort to establish Martin Luther King’s birthday as a national holiday.

But now that the noble deed is done, let’s confront the stark truth: One nation cannot have two independence days.

If you talk to people who grew up in Black communities throughout this country, they will tell you that most folks did not really celebrate July 4th. They focused their jubilation and commemoration on Juneteenth, because they understood that Black people in this country were not in any way liberated by the Declaration of Independence or the defeat of the Loyalists. In fact, our cause of freedom was better served by the very Brits who the colonists were set to defeat, as I pointed out in a column one year ago.

“If you talk to people who grew up in Black communities throughout this country, they will tell you that most folks did not really celebrate July 4th.”

The T-shirts you may have seen earlier this month tell the story: Black people have been free-ish since 1865. The fight for full freedom still continues, and part of that battle will require us to go further and further down the road of reconsidering what dates and which “heroes” we celebrate as a united people.

Does anyone reading this still believe that July 4th has any credibility as a day to celebrate “independence?” Does anyone reading this really believe that marking the day that propertied white men decided to lay formal claim to founding a slaveholding republic on stolen land is worthy of national celebration?

I suppose some would insist, “It’s part of our heritage,” as the defenders of Confederate monuments have done. What we must admit is that the heritage it celebrates is our nation’s original sin that nearly broke this country apart before it could mark 100 years of union.

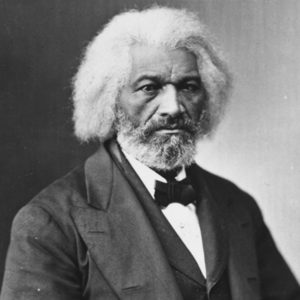

Frederick Douglass

More than a dozen years before the first Juneteenth, Frederick Douglass indicted the nation with a straightforward question and a scathing answer: “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.”

“This Fourth (of) July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

This is the true legacy of July 4th, “Independence Day” celebrations, and the reason why so many Black people celebrate Juneteenth instead of (and not in addition to) it. As Douglass stated concisely: “This Fourth (of) July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.” If the American people are really waking up to the sober truth of our history, then shouldn’t we all mourn? Shouldn’t we all declare that if this day was not for every American, then it really should not be celebrated by any American? That seems pretty American to me.

There will be those who will read this and suggest that I am engaging in the politics of division. But let us remember that truth never divides; it simply reveals. Then we have to make the decision — personally, and then collectively — about how we are going to respond to that truth. We can accept it, embrace it and try to come to terms with the changes we should make because of it. Or, we can deny it, reject it, rebuke it and then retreat to the dark corners of self-deception.

We decide whether or not to be united or divided by truth.

If it’s any consolation, I’ll still be singing along to Lee Greenwood’s “Proud to be an American,” next weekend just because I am a sucker for that song, and I grew up singing along to it while watching the Macy’s Fourth of July Fireworks Spectacular in New York City. But I know now that nobody who looked like me got free on that day. Our independence day has past.

So maybe as a nation, it’s time for us to pick (the right) independence day for all of us, and plot a new path forward together, as we strive to be one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

Paul Robeson Ford serves as senior pastor of First Baptist Church (Highland Avenue) in Winston-Salem, N.C. He was born and raised in New York City and grew up at the Riverside Church under the leadership of James A. Forbes Jr. He received a master of divinity degree from the Divinity School at the University of Chicago, where he is now a candidate for the Ph.D. in theology.

Related articles:

Juneteenth and the promise of freedom | Opinion by Darrell Hamilton

‘Thy kingdom come; thy will be done’: Independence Day and the Lord’s Prayer | Opinion by Kate Hanch

This July 4th, exercise your freedom to worship | Opinion by Barry Howard