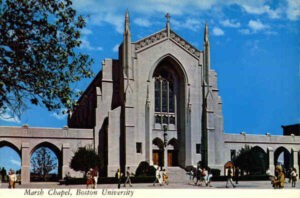

Sixty years ago, on Good Friday 1962, Civil Rights leader and minister Howard Thurman preached in Marsh Chapel on Boston University’s campus. Full of striking verbal imagery about Jesus’ suffering and God’s glory, his 85-minute sermon shook the otherwise silent chapel and was enough to bring any listener to tears.

For 10 seminarians just below him in an auxiliary chapel that day, there was more at work in their spiritual experience than a sermon. With Thurman’s knowledge, these seminarians listened to his sermon under the influence of the psychedelic drug psilocybin, more commonly known as the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms.”

Marsh Chapel, Boston University

These 10 seminarians and 10 others who received a placebo were the subjects of the Marsh Chapel Experiment, also known as the Good Friday Experiment. Doctoral student Walter Pahnke, a medicine and divinity student at Harvard, sought to record some of the first scientific data about psychedelic drugs and religious experience.

The effects of psychedelic drugs such as psilocybin, LSD or DMT are well-known today, but this was not the case in the early 1960s. Pahnke sought to establish that psychedelic drugs could cause religious experiences and long-term personal benefits for the user. He tried to gather evidence to support this thesis through observance of the subjects’ hallucinogenic “trips,” post-experience interviews and questionnaires.

A religious trip

Despite the clinical set up and parameters, it became clear that what was happening to Pahnke’s subjects was beyond his control and his experience. Psilocybin can cause intricate hallucinations and a sense of realization, often of a religious nature. That was the case for these seminarians. As one witness recalled, exclamations of awe such as “Oh, the glory!” and “God is everywhere!” began to arise from the research subjects. Some wept.

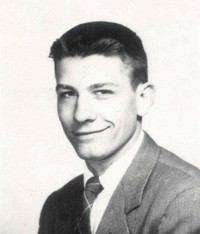

Walter Pahnke

For a testament to how out-of-hand things became during Pahnke’s clinical test, one need only compare how later testimonies about that day differ from his published dissertation. According to a personal recollection, one student became overcome with a desire to preach the coming of Christ. He was so overwhelmed by this conviction that he rushed outside to preach it in the streets. In the dissertation, Pahnke merely remarks that subjects remained inside “85% of the service,” while remarking that “only one subject” left the service with a leader because he was “restless.”

The 10 seminarians shared their experiences with Pahnke after a period of counseling and reflection. For someone unfamiliar with psychedelics, their testimonies may be difficult to fathom, for example:

QX: “Matter and time seemed to be of no consequence. I was living in the most beautiful reality I had ever known, and it was eternal.”

TD: “I had a vision in which the flowing colors seemed to be me. It was infinity.”

Others felt an intense need to praise:

FK: “I attempted to play the organ, wanting to play Christ the Lord is Risen Today, being motivated by a strange sense of joy.”

BL: “I immediately began to meditate and pray and read my New Testament — 1 Corinthians 13. … I began to pray for forgiveness and praise God for the blessings of life.”

One subject expressed that the experience affirmed their call to Christian ministry: “Before, I just felt as if I should enter the ministry, but now I know that I must.” This participant reported experiencing “a sense of ‘call’ — insofar as this means the word must be proclaimed to the ‘world.’”

In the end, most subjects reported long-term benefits to their religious and personal lives. With this data, Pahnke considered his Good Friday Experiment a success, concluding: “The drug experience is similar if not identical with changes resulting from mystical experiences.”

Other early psychedelic research

Richard Alpert and Timothy Leary at the time of the Good Friday Experiment , 1962.

Around this same time, Harvard researchers Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert tried and failed to convert or “turn on” famous theologians like Paul Tillich and Harvey Cox to psychedelics, but they were successful elsewhere. Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, a founder of the Jewish Renewal Movement, was one such convert. Huston Smith, a Methodist minister largely recognized in academia as the father of religious studies, was another. Smith also was present at the Good Friday Experiment.

Psychedelics became more prominent in other ways throughout the 20th century. Mormon prophet Frederick Smith, philosopher-theologian Walter Benjamin, and eventually Harvey Cox all had experiences with mescaline. Bill W., the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, compared his LSD trip to his conversion experience that led him to starting AA. He even considered integrating LSD into AA therapy. Research indicated that psychedelics could be used in therapeutic settings to heal mental illness.

At that time, the future looked bright for psychedelic research. That is, until the United States decided to criminalize psychedelics as a Schedule I narcotic. This designation ranks psychedelics to be more dangerous than methamphetamine, fentanyl or cocaine. Research on most psychedelic drugs ground to a halt, and the Good Friday Experiment became an obscure side note in religious history.

Making a comeback

But this is beginning to change again. On the legal front at the state level, there has been a notable shift. In November 2020, Oregon legalized psilocybin therapy. Several cities in the United States, including Washington, D.C., and Denver, have decriminalized possession of psilocybin. Bills from both Republican and Democratic state governments recently have attempted to decriminalize or otherwise improve access to psychedelics.

This recent shift has had a significant effect on usage. From 2015 to 2018, there was a 50% increase in LSD use, and researchers have suggested that its use has tripled since the pandemic began. Use of other psychedelics such as psilocybin have probably followed similar trends.

Meanwhile, therapeutic research has emerged once again. Therapy using ketamine, a Schedule III psychedelic, already is accessible nationwide to treat depression and other forms of mental illness. Within the past few years, researchers have demonstrated that psychedelic therapy can be useful for treating depression, anxiety, PTSD, addiction and other ailments.

Often a potent religious experience

So what does this all mean for Christians today, and how can the Good Friday Experiment help us face this psychedelic revolution, albeit 60 years later?

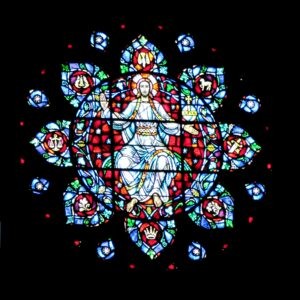

The Rose Window in Marsh Chapel

Despite attempts to fit psychedelic experiences into secular frameworks, they are still interpreted as religious experiences. Walter Pahnke’s clean, clinical experiment failed to encapsulate or anticipate the intense religious nature of the psychedelic experience.

Even if these experiments are happening in clinical settings or a friend’s basement devoid of religious iconography, psychedelic trips are still described in religious terms. According to one self-report survey, about two-thirds of people who were atheists before a psychedelic experience stopped identifying as atheists after it. Decriminalization of psychedelics in Seattle was even justified on the grounds that these substances were entheogens, roughly translated as “possessed of God.”

With this knowledge at their disposal, Christians should, at a minimum, become more informed and proactive when discussing psychedelics. Christians may be comfortable debating nuanced and moderated positions about alcohol or marijuana use, but are we ready for this conversation? Are we ready to accept a military veteran in our family or friend group when they open up about their therapeutic MDMA or psilocybin use? Can we listen to a college student who overcame religious trauma through taking LSD? Are we prepared to affirm a terminally ill cancer patient taking psilocybin to ease their death anxiety?

Another cultural shift

Further, the Good Friday Experiment reminds Christians not to get comfortable in our sectarian debates of the recent past and present. Psychedelic use in the early 1960s was only one sign of the counterculture explosion that was to come in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is possible that the psychedelic reemergence today is only one sign of a larger cultural shift.

While Baptists in particular are often mired in the same theological debates of the 1980s and 1990s, American culture is progressing at a sometimes bewildering pace. Just as the Good Friday Experiment has shown, religious folks are not immune from the effects of this shift.

If we make the choice to keep tabs on these societal trends, we can be more proactive in anticipating where ministry might be needed in the future, and we may possibly even learn new skills in drawing people to the gospel. As Jesus and Bob Dylan reminded us, if we recognize the sign of the times, we “don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

Two primary research sources for this article were The Harvard Psychedelic Club by Don Lattin and Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experience by William A. Richard.

Author’s note: This article is not an argument for illegal drug use or activity, and it should not be construed in that manner. All drug use is inherently hazardous, and recreational use without an attending physician can cause immense harm.

Kaleb Graves

Kaleb Graves was ordained as a CBF minister in 2019 and has served churches in Arkansas. He is currently a Baptist student at Duke Divinity School pursuing the master of divinity degree.