I watched a movie one night recently called Selma. It was about the 1965 freedom march in Selma, Ala., led by Martin Luther King Jr. Given all of the turmoil now roiling our country regarding Black Lives Matter, I wanted to be reminded of what a leader King was for all of us. But it also reminded me of another moment in my life, one that occurred in 1961.

My father, who had served as pastor of several Southern Baptist churches, had taken the job at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky., in 1957 as dean of students. It was an important “homecoming” for him as he grew up in Louisville and was a graduate from Southern Seminary with what was then a doctor of theology degree. One aspect of that job at Southern was that he was also, effectively, dean of the chapel.

Bill Thurman

In 1961, and motivated by encouragement of several professors at Southern, Martin Luther King was invited by a committee of professors to come to the seminary for a visit, to speak to an ethics class and, more importantly for me, to speak at the seminary chapel service, where all the students and faculty were to be in attendance.

Not a small matter at that day and time, as Southern Baptists were not in the forefront of promoting the civil rights of all. In fact, the result of such an invitation, and of King speaking at the seminary, was an incredible outcry by many Southern Baptist churches condemning the seminary for such a “brazen” act, as well as a symbolic “defunding” of the seminary by those churches. Fortunately, the funding for the seminary at that time came from a variety of sources, so it survived.

The part that was important to me, however, was that my father asked me, and even encouraged me, as a then 13-year-old, to attend that chapel service, even though I had to miss part of my junior high classes that day to do so. Fortunately, the principal at the junior high was very much in favor of my going.

I got to listen to Martin Luther King, but more importantly, I got to meet him personally and shake his hand after the chapel service, a moment I never will forget.

“His reason for wanting me to meet King had less to do with the great orator than it had to do with Josie.”

It pleased my father also. But his reason for wanting me to meet King had less to do with the great orator than it had to do with Josie.

I was born in Hopkinsville, Ky., where my father was pastor of First Baptist Church. I loved Hopkinsville and, in particular, the members of that church. You talk about great memories — I had them of Hopkinsville. Because my father, and my mother as well, were active not only in church work but also in the community, there were many times my sister and I had to have a sitter with us until we reached an age when we could more readily take care of ourselves. Josie was that person.

I do not know for sure, but I would guess Josie was either in her late teen years or early twenties when she came to sit with my sister and me. It didn’t take long for us to figure out that Josie was like a big sister or even a surrogate mother for us. She was filled with genuine love and caring for us. I trusted her completely with my well-being. That gave my parents great relief that she was the best person to care for us in their absence.

I entered the first grade at Virginia Street Elementary School in 1954. It was scary at first, but I soon learned it was a good place. One of my companions at school was a neighbor up the street. Phillip was virtually my best friend at the time, as we played together in our neighborhood, to which we had moved two years earlier, and got to know each other well. It was during that first-grade year that, while playing with Phillip, he told me that his parents had just advised him of something terrible that was going to impact Virginia Street and make it a dangerous place for us. He told me he had just heard (through his father, I believe), that the U.S. Supreme Court (whatever that was) had just ruled that the N-people had been given the right to enter our school.

I immediately ran home to tell my mother this story and to find out what we were going to do. Clearly, those of us in school were in danger, even though I had to confess to her that I didn’t really know who the N-people were. My mother smiled at me lovingly, which at that moment I really needed as she did not seem to be overly worried, and she said when my father got home, he would explain.

Late that afternoon, after my father got home from church, he sat down with me in the living room. I told him what Phillip had told me, and I told him I did not know who the N-people were, but Phillip indicated that his father thought they were dangerous. My father listened carefully to what I had to say but did not respond immediately. So I said, “Dad, who are the N-people?”

My father then looked at me carefully, but lovingly. His answer was, “Well, Bill, I am going to explain everything as best as I can. But you need to know, up front, that one of them is Josie.”

“My world, my life, changed dramatically at that moment in my 6-year-old life.”

My world, my life, changed dramatically at that moment in my 6-year-old life. Josie is too caring and loving to be what Phillip told me she was. I couldn’t understand. For the next several minutes, my parents, together, explained what the “N” word meant, and what the term Negro meant, and how ignorance, bias, history and people had distorted it. They also talked about how important Josie and her life was in trying to educate people as to their misconception, and how, in time, I might be able to help enlighten people.

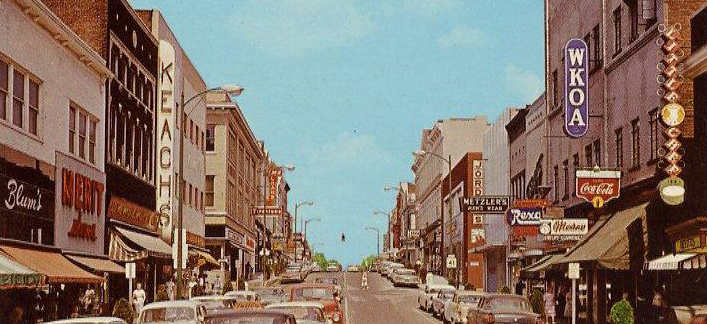

To help enlighten me in my journey, my father, not long after this occasion, asked me to go with him to pick up Josie to bring her back to our house so she could watch over my sister and me. We drove through downtown Hopkinsville to the other side of town, just past the railroad tracks, to a place I never had been before. After we turned at the tracks, the dirt road went downhill so that the railroad tracks were above.

And what they were above were, to put it as plainly and bluntly as I can, shacks and shanties, one right after another. All the same. Al in terrible condition. All inhabited by people like Josie. Indeed, this was where Josie lived with her family. I looked at my father and said, “Dad, why would people choose to live like this?”

As my father often would do, when he wanted me to figure out things on my own, he said, “Indeed.”

Not too long after that time, my father decided to take me on a tour through Hopkinsville. He showed me several buildings in town that housed stores, offices, restaurants. One of those places was a small restaurant in town that was actually owned and operated by Phillip’s father. A wonderful place that I, and many others, loved to go to and which became famous in its own right. We actually concluded our trip at that restaurant.

Dad said, “Bill, did you notice anything about those places I showed you?” I told him I really didn’t notice anything special, as they were places I had seen, or even been to, many times before. He then said, “Let me take you to the back of the building.” He showed me the back door that led to the kitchen. At the top of the door was a sign that, although I was only a first grader, I could read. It said, “Coloreds Entry.”

I told him I did not know what that meant. What are “coloreds?” I asked. Dad looked at me and said, “Josie is one.”

Then he took me back to the front of the building and showed me a sign I had not paid attention to, except I knew I had seen it on other buildings. It read “Whites Only!” At the end of our tour, I was completely confused about life, except I knew we could not ever take Josie to dinner in such a place.

“At the end of our tour, I was completely confused about life, except I knew we could not ever take Josie to dinner in such a place.”

That is the way my journey began in trying to figure out why we treat different people differently. My ultimate conclusion was that we cannot, at least not in the loving eyes of God.

I had one more trip to the shantytown where Josie lived, maybe a year or so later, but before we moved to Louisville. My father rushed home and said, “Bill, we need to go check on Josie.” I had no idea what was going on and afraid to ask, but when we got to the railroad tracks, I understood what all the smoke I had seen billowing up was for. The shantytown was on fire, with virtually all the houses on fire.

To this day, I don’t know if the fire was accidental or intentionally set, but the damage and casualties were significant. We found Josie and her family alive, although standing outside their heavily damaged home. My unspoken but internal prayer had been answered as I had prayed it. My beloved Josie was still around.

I do not know this for sure, but I suspect my father, through the help of others (particularly church people), took care of Josie and her family as best they could. Probably helped the others as best as possible also.

Some 30 years or so later, my father, in his retirement, agreed to serve as an interim pastor at First Baptist Church while the church was looking for a new pastor. There had been several pastors of the church after my father left to go to Southern Seminary, but the church was dealing with issues they thought my father could help them deal with better if he were their interim.

That took me to Hopkinsville one last time, but this time with my own family. While driving through good ole’ “Hoptown” one more time, with my father driving, he paused at an intersection, pointed outside of the car and said, “Bill, that’s Josie standing there.” To this day, I do not know if this was set up or not, but I didn’t care. I was able to hop out of the car and give Josie a hug one last time.

And now another 30 to 35 years have passed in my life, and yet, we, as a people, are still dealing with issues of race and ethnicity. I hear people say it is a complicated issue. I don’t have a very good answer for people who say such things. All I can say to them is, “I am sorry you didn’t meet Josie when you were a child.”

Love can overcome all things, if we will let it. Josie taught me that, with guidance from my father, and not coincidentally, through God.

Bill Thurman is an attorney in Lexington, Ky. A lifelong Baptist, he has been connected to only three churches: First Baptist Church, Hopkinsville, Ky., where he was baptized; Crescent Hill Baptist Church in Louisville, whose pastor in 1961 was John Claypool; and Calvary Baptist Church in Lexington, Ky., where he has been a member 50 years.

Related article:

The other speech Martin Luther King gave at Southern Seminary in 1961