In the wake of the Guidepost report that Southern Baptist Convention executive leaders covered up knowledge of sexual abuse for decades, we are reminded once again of how religious abuse has deeply traumatized millions of our neighbors.

One of the ways evangelicals have processed a growing awareness of religious abuse has been through starting conferences. The Exiles in Babylon Conference offered many helpful insights to racial trauma but continued to advance narratives that have caused sexual trauma in the church. The Restore 2022 Conference brought complementarians like Karen Swallow Prior and egalitarians like Scot McKnight together to discuss topics such as where God is during abuse, healing from religious trauma, and how churches enable abuse. Their goal was to address these issues within the framework of “restoring faith in God and the church.”

Because spiritual growth tends to evolve slowly, conferences such as these can be helpful for evangelicals to begin becoming aware of how power dynamics within their worlds foster abuse.

But too often with these conferences, there are underlying theological assumptions that fuel power dynamics that do not get questioned to the degree that they should. And when your stated goal is to restore faith in the church, you have theological territory to protect and are invested in a certain outcome that people who have been traumatized by the church may not be ready for or interested in.

Many people are having enough and deciding to leave evangelical churches while mourning the loss of their communities and hoping to discover a healthier experience of Christianity.

But many are leaving Christianity altogether.

Listening or talking?

Because conservative evangelical media outlets such as The Gospel Coalition continue to bloviate about those who are either deconstructing or deconverting, one has to wonder: Are conservative evangelicals at all willing to sit quietly and listen to those who have left?

And are progressive evangelicals any healthier at silent listening?

“Must Christians always be leading and talking?”

Imagine a space for processing such religion-fueled trauma that is led by formerly religious people for formerly religious people. Would it be possible for religious people to sit in silence and learn from atheists and agnostics about how their religion has caused deep trauma, consider how the formerly religious are healing, and learn from their insights in order to heal themselves?

Or must Christians always be leading and talking?

Janice Selbie

The Conference on Religious Trauma held its second annual meeting this month to create a space for these conversations. In an interview with Baptist News Global, Janice Selbie —founder of the conference — explained, “Christians, both fundamentalist and progressive, have plenty of support. CORT was developed for those outside such support. It’s a space where those recovering from the harmful impacts of religion can find validation and encouragement as they build healthy new secular lives.”

“There are widespread assumptions that religion in general is good or at least harmless,” CORT’s website explains. “Yet people are seriously hurt by religious doctrines and practices every day. This has to end.”

What is religious trauma?

CORT’s website defines religious trauma as “a set of symptoms and characteristics related to harmful experiences with religion.”

It goes on to explain: “We intend to make evident the adverse ways in which religion can affect individuals both immediately and long term. We seek to clarify the way personal psychology interacts with religion to create suffering that is properly called trauma. We are committed to developing ways to relieve that suffering and treat religious trauma. We want to disseminate this information to our culture — in fields of mental health, education, the justice system and other areas of society. No longer will the damaging effects of religion be a widely held secret among survivors, and no longer will they be treated as invisible.”

This year’s conference brought together professionals in each of these fields who helped attendees grow in awareness of how religions have caused trauma in their hearts, minds and bodies and how they can begin to heal.

Religious trauma flows through theology

Theology is the water Christians swim in. So it can be difficult to recognize how the theological environment affects us and those around us.

“Theology is the water Christians swim in.”

Selbie told BNG: “Religious people believe their religion is the one true faith, or they wouldn’t practice it. If they believe their holy book is true for them, it must be true for others. This means some people are sinners by religious standards and must be either corrected or rejected by religious people.”

Marlene Winell, a psychologist and author of Leaving the Fold: A Guide for Former Fundamentalists and Others Leaving Their Religion, said during her session that the two assumptions of abusive theology are that “You’re not OK” and “You’re not safe.”

Marlene Winell

The idea that “You’re not OK” flows directly from the theology of original sin, which is the teaching that humans inherit a sinful nature and the penalty of death simply by being born as a physical descendent of Adam. And the idea that “you’re not safe” flows directly from the theology of eternal conscious torment.

“The idea (is) that you are basically bad, that you were born a sinner, that there’s something wrong with you in essence, that it needs to be fixed, that you’re supposed to spend your life feeling grateful even though you can’t live up to the expectations anyway and there’s no guarantee that you were saved in the first place,” Winell said.

Abusive theology preys on our deepest human longings

Theology by definition is concerned about the ultimate questions in life: questions about whether there is a God, why there is something rather than nothing, the purpose of life, our relationship with ourselves and everyone around us, and what happens after death.

As children, we long for the love and affirmation of our parents. And yet, we’re afraid of how big the world is and how insufficient our understanding of it feels.

In some ways, we’re asking, “Are we OK? And are we safe?”

“Religion promises certainty, security, order and community. People remain religious for those very reasons, as well as fear of hell.”

Selbie told BNG: “People embrace religions because they were born into them or turned to them during times of transition and vulnerability. Religion promises certainty, security, order and community. People remain religious for those very reasons, as well as fear of hell.”

For the formerly religious to walk away from their certainty, security, order and community can be one of the most vulnerable decisions anyone ever makes. “Divorcing religion means loss of family, community, support and identity. It is too hard for many even to consider,” Selbie said.

To walk away from the certainty of heaven is to embrace the possibility of hell. To walk away from the theology of your family is to embrace the disapproval that you spent years trying to avoid. To walk away from the support of your church community is to embrace the possibility of nobody being there for you when you face a life-threatening illness or when you simply want to hang out with familiar friends.

Deconstruction and deconversion can be like Pinocchio leaving the identity-forming, punishment threatening world of Pleasure Island and moving toward Monstro the whale — the ultimate danger everyone around you fears — for the sake of being present with who you’re learning to love, namely yourself and your neighbors.

But abusive theology preys on our mental, social, spiritual and sexual longings and infuses within us an identity that we’re fundamentally a problem and that we’re forever going to be punished.

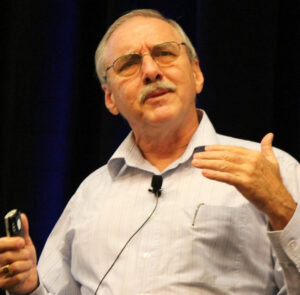

Darrel Ray

Darrel Ray, founder and president of Recovering From Religion, explained during his session, “It’s like you can’t utter the word ‘sex’ without the word ‘sin’ coming out within the same sentence in almost any religious environment, especially if it’s conservative or fundamentalist. … The ideology itself plays a role in the trauma you experience.”

Of course, many kinder, gentler evangelicals might object, thinking that somehow you can hold to theologies that form negative self-identities and that celebrate justice through violence without being abusive, or suggesting that Christians are much kinder than in centuries past. To that defense, Ray asserts: “We may not be lopping people’s heads off. But I’m telling you, I’ve met plenty of Baptists who have been traumatized by the ideology of their Baptist faith and their church because there’s nowhere for a child to escape if they’re in that church and they’re constantly being told the outside is dangerous.”

How atheists and agnostics have clarity

In a recent podcast episode, author and former megachurch pastor Rob Bell said: “The water, if you’re a fish, is so difficult to see. The reason it’s so difficult to see is because everyone around you is swimming in it. There’s no observance of it because it’s the thing everybody’s immersed in. It’s too close to see.”

Formerly religious people have had the experience of swimming in the water that religious people exist in, yet currently have the perspective from standing on the beach.

According to Selbie, it is not merely enough for Christians to redefine the water they’re swimming in to a more progressive understanding. She believes true perspective and the fullest healing comes when people leave the water altogether.

“She believes true perspective and the fullest healing comes when people leave the water altogether.”

“I think even progressive Christians are still ‘drinking the Kool-Aid.’ I don’t typically invite still-religious people to speak at CORT because I think continued affiliation with the Bible is unhealthy when it comes to the LGBTQ community, safety of children and women’s rights.”

Progressive Christians tend to object. “In public and private, I receive angry input from ‘progressive’ Christians for not inviting them to speak at CORT. I won’t risk further traumatizing attendees by doing so, although I do still have Christian family. I do not think it’s possible for evangelicals or other religiously entrenched people to be trauma sensitive with regard to religious trauma, although they vehemently disagree.”

While Selbie would admit that not even all her conference speakers would agree with her belief in the necessity of leaving the water altogether, her assertion that religion encourages “fantasy over reality and often creates massive division (in family and nation) and trauma (individual and collective)” has been demonstrably true.

Atheists and agnostics who spend significant time invested in the church are especially positioned to bring clarity to how theology fosters abuse because they know the theology, they’ve experienced the power dynamics involved, and because they are free to question every facet of Christian theology and power.

Russell Moore and an insufficient response

In his response to the Guidepost report on sexual abuse in the SBC, Russell Moore said his “hands were shaking with rage” and that the report displays “the sort of inhumanity one could hardly have scripted for villains in a television crime drama,” called the abuse a “criminal conspiracy” and “blasphemy,” and concluded that “anyone who cares about heaven ought to be mad as hell.”

Regarding the theological justifications SBC leaders used to cover up sexual abuse, Moore noted sexual abuse victims “were also isolated with implications that if they kept focusing on sexual abuse, people wouldn’t hear the gospel and would go to hell.”

While I appreciate Moore’s rage, his response is still insufficient. He admits they justified their cover up of sexual abuse due to their theology of hell. But he still won’t question their theology of hell.

“He admits they justified their cover up of sexual abuse due to their theology of hell. But he still won’t question their theology of hell.”

Conservative evangelicals owe it to the victims of sexual abuse they ignored and demonized to reconsider the theology of hell they used to dismiss them.

Moore has been one of the most vocal supporters of sexual abuse victims within the world of conservative evangelicals. And yet, even he seems unwilling to root out the theological seeds of power that fuel abuse based on support of eternal conscious torment and male headship.

When you read about sexual abuse cover ups in the church through the Guidepost report or any future reports, notice whenever you hear the defenders of cover ups mention hell, evangelism and missions. Then at least have the theological curiosity to ask some questions about the motivations these men explicitly use.

The formerly religious at the Conference on Religious Trauma have no theology of hell or male headship to protect. They simply have a passion for people to heal from the trauma such theologies fuel.

Healing from religious trauma and taming your monster

The strength of the Conference on Religious Trauma was in the passion and wisdom of its speakers to foster healing.

Darrel Ray spoke about religious trauma and sexual identity.

Jennifer French discussed how to recognize, prevent and heal from coercive control in either domestic or interpersonal relationships.

Beatrice Weber, Elam Zook, Jerusha Lofland and Ryan Stollar examined how unregulated homeschooling creates an environment that has been used to traumatize and control kids within the Jewish Ultra-Orthodox, Amish and white evangelical communities.

Clint Heacock explained how Christian dominion theology has given rise to Christian nationalism and has caused religious trauma.

Amal Alhuwayshil explored the five stages of sexuality that get cut off as a result of religious trauma and shared ways to heal in order to experience sensuality, joy and pleasure.

Emily Hendrick talked about how we can heal in the present without having to live in the past.

Jeremiah Camara shed light on how religious iconography fuels racial harm.

In one of the more practical presentations, Caleb Lack shared specific steps people can take in order to overcome their anxiety about suffering for eternity in hell.

Luna Corbden shared what cult researchers have discovered about untangling from belief systems in ways that resonate with your personality and values and that protects from manipulation in the future.

Dan Barker and Louise Snowdon spoke about connections between Christianity and colonialism and the effects these connections have had on Indigenous people.

Mandisa Thomas discussed how white supremacy infused into a uniting of church and state has affected communities of color and how those trends can be reversed.

David Teachout taught about how healthy communication and dialogue built on common foundations can build relationship.

Candace Gorham walked through how those who leave their faith can move through the mourning and grieving process.

A fire-breathing dragon

Then the conference concluded with a beautiful presentation by Marlene Winell, who opened up with a fire-breathing dragon puppet over her right shoulder. She said when children grow up and leave their religion, their past religion often can remain present with their minds, hearts and bodies like a monster over their shoulder.

Winell said this trauma “gets stored in the body. Trauma is your nervous system’s response to some threat. And you are processing it as a life and death kind of situation. And it creates a lot of fear. It creates physiological response. You get cortisol and adrenaline running in your body. You’re having a fight or flight or freeze kind of response.”

“A huge thing in the healing process, and something that’s absolutely necessary in the healing process, is that you have compassion for yourself, you learn to have compassion for yourself.”

But she reminded: “It’s not really a choice when you’re in a family, a church, a community, when you’re homeschooled, when you’re not given any information about any alternatives. It’s not a choice. And so you get these ideas in your impressionable mind as a child, and they go deep down. So a huge thing in the healing process, and something that’s absolutely necessary in the healing process, is that you have compassion for yourself, you learn to have compassion for yourself. And one way of developing that is to realize that you have an inner child. You have a part of you, a part of your personality that’s still a little child that will always be innocent and pure, that just wants to live and be happy, has a lot of feelings, has a lot of normal human needs, and will always be with you. Your child is not going to grow up and go anywhere. Your child might be wounded, deeply wounded. But nevertheless, a child can certainly have some healing.”

Winell went on to discuss how to recognize healthy fear in contrast to fear as a trauma response, how to distinguish the difference between the idea monster of your former religion and your inner critic. And then toward the end, she removed the dragon puppet from her shoulder and placed a small, green frog in its place.

By taming your monster into a small frog, the trauma that once felt loud and heavy can be heard and healed with a love for the child within and for the adult who now lives, she said.

Note: Sessions from the 2021 conference are still being uploaded to the group’s YouTube channel, and videos from this year’s event will be uploaded around spring 2023. However, to watch the 2022 recordings now, purchase a resource ticket.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a bachelor of arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

As a religious abuse survivor, this is my message to Baptist pastors | Opinion by Lydia Joy Launderville

Therapist guides clients through loneliness, trauma created by spiritual abuse

Can God be found outside Christianity? | Opinion by Amber Cantorna