On the evening of Dec. 30, NBC concluded the national news with its annual “In Memoriam” segment for 2021. Some 90 singers, musicians, composers, actors, filmmakers, television personalities, professional and amateur athletes, coaches and managers, writers, and even an Apollo astronaut were remembered. So were a variety of politicians and civil servants — including U.S. senators, cabinet members, a vice president, and a presidential candidate, as well as the Duke of Edinburgh, husband of Queen Elizabeth II.

To be honest, I usually watch such memorials during major award shows or end-of-year recaps with rather mild interest, primarily to be reminded of the names and faces of those who have died in the previous 12 months. Until this year.

Robert Sellers

Suddenly at age 76, having had three surgeries in the past 18 months and possibly facing one or more others soon, I was not just mildly interested. It occurs to me that I am older than many of the famous deceased who are being honored. More to the point, I realize I have outlived numerous high school and college classmates, colleagues at the places where I have worked, fellow church members, and other friends I have known, along with some relatives, close or distant.

I also realize that when I die, no one will see my face and name included in NBC’s list of celebrities. For I will not be a “towering figure.” I will not have earned any Emmys, Grammys, Oscars or Tonys. I will not have won any Superbowl championships, NBA or NHL rings, Olympic medals or racecar titles. I will not have been elected to any local, regional or national offices. In short, I will not be a celebrity and thus will not be remembered in any “In Memoriam” list.

Of course, being a “celebrity” doesn’t guarantee that one is widely known. I confess that I never have heard of some of NBC’s remembered notables.

Sharon Marcus, a Columbia University professor of English and comparative literature, discusses the phenomenon of publicly “important people” in her book, The Drama of Celebrity. She distinguishes between two related words, “fame” and “celebrity,” noting that fame is a Latin term (fama) that dates from the time of the Romans to indicate that one’s great deeds would be remembered for millennia, while there was no ancient term for celebrity, which might not be lasting at all.

Her grasp of the temporary nature of much, but not all, celebrity is consistent with how such fleeting popularity or public fame is defined online:

Celebrity is a condition of fame and broad public recognition of an individual or group as a result of the attention given to them by mass media. A person may attain a celebrity status from having great wealth, their participation in sports or the entertainment industry, their position as a political figure, or even from their connection to another celebrity. “Celebrity” usually implies a favorable public image, as opposed to the neutrals “famous” or “notable,” or the negatives “infamous” and “notorious.”

Sarah Bernhardt

Professor Marcus notes that the first person to enjoy celebrity status, as it is understood today, probably was the French actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923). She explains:

Bernhardt became the godmother of modern celebrity because her career coincided with several inventions that she cannily used to promote herself. The rise of photography made pictures of her widely available. The penny press — cheap mass-circulation newspapers — trumpeted her every role on stage and her doings offstage. Steamship and railway travel allowed her to tour the world as few actors had before. Telegraphy was brand new, and news about her could travel faster. Almost everyone had heard of her, read about her or seen her picture.

It is easy to see how a century later, contemporary celebrities utilize photographs, newspapers and magazines, tours and the internet to put their faces and names before the masses. But is this celebrity lasting?

BuzzFeed, an American Internet media news and entertainment company, is committed to tracking viral content and public opinion. Just a month ago, a member of the BuzzFeed staff asked their regular followers to vote whether a group of current celebrities would be remembered or forgotten 100 years from now.

Dave Stopera posed a diverse list of the popular — from Beyonce to Lebron James, Meryl Streep to Sir Paul McCartney and Elon Musk to Dick Cheney. The results were surprising: the majority of respondents felt that very few of the celebrities would be remembered, regardless of how “famous” they are now. Not surprisingly, most celebrities were judged likely to become one of the forgotten persons of the past. To support their votes, many who participated in BuzzFeed’s poll commented that they couldn’t recall a single celebrity from the 1920s.

If “important celebrities” whom we honor today may realistically be forgotten tomorrow, isn’t it even more crucial that those of us who are neither publicly famous nor popular should consider the legacies we may leave behind us when we are gone?

“Isn’t it even more crucial that those of us who are neither publicly famous nor popular should consider the legacies we may leave behind us when we are gone?”

Although we Americans generally don’t like to think about death, we are still fascinated with the way celebrities answer the frequently asked question: “How would you like to be remembered when you die?”

Some of these responses are sadly frivolous, while others — like these I quote below — are quite profound.

- Rosa Parks responded: “I would like to be remembered as a person who wanted to be free … so other people would be also free.”

- Rupert Murdoch said, “I would like to be remembered, if I am remembered at all, as being a catalyst for change in the world, change for the good.”

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg offered: “I want to be remembered as someone who used whatever talent she had to do her work to the very best of her ability, and to help repair tears in her society.”

- Frank Sinatra mused: “I would like to be remembered as a man who had a wonderful time living life, a man who had good friends, (and a) fine family.”

- Malala Yousafzai replied: “I don’t want to be remembered as the girl who was shot; I want to be remembered as the girl who stood up.”

- Betty White, who died on Dec. 31, 2021, just 17 days short of her 100th birthday, proposed: “I want to be remembered (as one who) made people laugh… and think a little.”

- Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who died on Sunday, Dec. 26, 2021, and was given the coveted last position in NBC’s “In Memoriam” cavalcade of greats — traditionally reserved for the most important or best loved celebrity — answered: “I want to be remembered as one who was forgiven and was forgiving.”

What if there were an “In Memoriam” for regular people like us? Or, to be more specific, what if there were an “In Memoriam” for Christian people like us? How would we want to be remembered? Instead of the single word or short phrase that editors at NBC annually give to identify the celebrities who have died, how would we want to be summarized and identified?

Can we imagine an “In Memoriam” each year put together by the editorial staffs of Christian organizations? Would it be something like this fictitious listing, accompanied by photos of these little-known believers in action?

- Bill Anderson – crisis counselor

- Mary Jones – megachurch pastor

- Henry Rodriguez – prison chaplain

- Danny Wright – orphanage houseparent

- Jill Smith – denominational administrator

- Philip Alvarez – religion professor

- Holly Daniels – nonprofit executive

- Thomas Mbibi – interfaith advocate

- Benjamin Rogers – curriculum writer

- Lucy Lim – youth minister

- Barbara Williams – spirituality instructor

- Frank Jones – camp director

- Amy Cummings – Sunday School teacher

If there were such a “In Memoriam” for people like us, how would I want to be remembered? As one who desires seriously to think about my life and faith, I should be considering this question. And, by extension, others of us who want to give careful attention to our legacies should be thinking about this question.

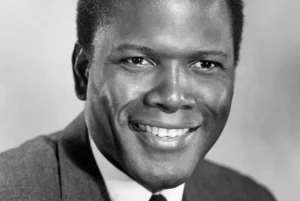

Sidney Poitier

Interestingly, a helpful resource comes from a blog posted on an internet site which promotes itself as “your trusted source for end-of-life planning.” The blog begins with a quote from the famous actor Sidney Poitier, who said: “If I’m remembered for having done a few good things, and if my presence here has sparked some good energies, that’s plenty.” Then it comments: “We all want to leave behind a legacy. Mr. Poitier is a cultural icon as well as a revered actor. His legacy is a powerful reminder of the enduring force of an extraordinary life lived to its fullest. Unfortunately, we can’t all be boundary-breaking artists, but each of us has within us the chance to be remembered for making a positive impact on peoples’ lives. The drive to live a life full of meaning and love, one that resonates throughout history long after we’re gone, is only natural.”

Here are the funeral blog’s four steps for being remembered well: 1) Be authentic; 2) Be loving; 3) Be helpful; and 4) Be thoughtful.” These are good suggestions. In fact, I suspect we could easily find supportive Scripture passages to undergird these simple actions we might embrace in order to prepare for the time when we too will be remembered. I suggest these biblical connections:

Be authentic. “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God” (Matthew 5:8). We should not be two-faced, duplicitous or fake. Our walk should be consistent with our talk. Our “yes” should mean yes and our “no” should mean no. We need to be known as genuine and real.

Be loving. “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets” (Matthew 22:37-40). We should love all our “neighbors,” and not just those who are like us or part of our own group. Those neighbors comprise people both near and far, and even include our enemies. In a larger sense, our “neighbors” are also the earth itself and all of its creatures, of which we are to be faithful stewards and caretakers.

Be helpful. “Bear one another’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ” (Galatians 6:2). We should recognize our common humanity and do what we can to lift up the fallen and encourage the struggling. We cannot be helpful only when the good deed we perform somehow will come back to benefit us.

Be thoughtful. “Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves” (Philippians 2:3). Being truly thoughtful of others is often time-consuming, costly, criticized by others or inconvenient. As the saying goes, “People don’t care what we know until they know that we care.”

“Maybe our being authentic, loving, helpful and thoughtful will make us memorable in the eyes of those with whom we interact.”

These funeral home suggestions are somewhat trite, and my scriptural connections admittedly simplistic. But maybe we do not need difficult instructions. After all, the prophet Elisha told Naaman to go dip his leprous body in the dirty water of the Jordan River seven times. It wasn’t as complex or as challenging as the great military commander of Aram expected but following Elisha’s advice cured his dreadful disease.

Perhaps, then, the dis-ease that so many of us experience today doesn’t require a complicated or grandiose fix. Maybe our being authentic, loving, helpful and thoughtful will make us memorable in the eyes of those with whom we interact.

And while there will likely never be an “In Memoriam” for people like us, we will indeed be remembered, either positively or negatively. Those who know us, love us, serve with us, follow us or lead us — who are related to us, live beside us, work or play with us — will observe us and evaluate us. Thus, shouldn’t we be thinking about how we wish to be remembered?

To prepare ourselves for our own “In Memoriam” notation some day: What a beneficial New Year’s resolution that would be.

Rob Sellers is professor of theology and missions emeritus at Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon Seminary in Abilene, Texas. He is the immediate past chair of the board of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. He and his wife, Janie, served a quarter century as missionary teachers in Indonesia. They have two children and five grandchildren.

Related articles:

‘It is finished’: The spiritual practice of daily examen | Opinion by Jayne Davis

Five tips from the dead about living life in the new year | Opinion by Mark Wingfield