Christian nationalism is gaining ground among Republicans, they say — and I’m not sure who “they” is, but it could be somebody who knows what they’re talking about.

I am trying to learn about all this because it has to do with two things very important to me: my religion and my country.

Here is what I have learned.

Dwight Moody

Christian nationalism is a political ideology asserting that Christian people and Christian values need to dominate our country if we are to reach our potential as a nation. They claim the nation was founded by Christian people affirming Christian values and this twin influence has, over time, disappeared. They want to bring it back, which is why they latched onto Donald Trump and his “Make America Great Again” slogan.

I once interviewed a person who embraced that slogan. I asked him to clarify for me when exactly it was that America was great. He mumbled something about the 1950s. I said, “You mean that decade when women could not attend seminary or law school and Blacks rode in the back of the bus?” He apparently had not thought about that.

But the 1950s is precisely the time when this movement now called Christian nationalism emerged onto the public scene: 1957 to be exact, when President Dwight Eisenhower dispatched federal troops to Little Rock, Ark., to protect Black students who were attending school with white kids.

A few years later, Bob Jones University was stripped of its nonprofit status because it refused to adopt race-neutral policies on its campus in Greenville, S.C. This was a small stop in a 60-year stretch of public life during which the federal government insisted on compliance on a series of things that irritated people: quit reading the Bible over the school intercom, they said, and marry a person of another race if you want; get an abortion if you wish and, if you are gay, get married, get a job, buy a house.

All these efforts to provide equal opportunity to all people upset so many people in the South, they launched a war — a culture war, they called it, using the language of the battlefield so as to properly label their opponents as “enemies” and motivate their sympathizers to extreme measures. At rock bottom, these cultural warriors want the federal government out of everything except national defense.

“All these efforts to provide equal opportunity to all people upset so many people in the South, they launched a war.”

While this race-based vision was arising in the South, scholars from Europe set in motion a very different challenge to modern American life. “How Then Shall We Live” one titled his book about the matter, and he answered his own question by calling for Christians to enter all fields of endeavor and influence them with the gospel.

That was expatriate American Francis Schaeffer, and he got many of his ideas from the Dutch politician and theologian who famously wrote, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!’” That’s from Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920).

These expansive visions of Christian influence took the form of what is now called Dominionism, as systematized by a man curiously named Rushdoony. He identified seven cultural areas over which Christian should exercise dominion: religion, education, arts, media, business, government, family.

There is clearly some dissonance between these two streams of political engagement — the first wishing the federal government would leave everybody alone and the second pushing everybody to take over the levers of power (including at the federal level) so as to create the country they want.

Now comes the third ideological force exercising great influence on what we now call Christian nationalism, and it comes out of the Pentecostal culture.

Normally, Pentecostals live and work on the edge of public life, largely unnoticed and without much influence. But decades ago, John Wimber and Peter Wagner set in motion a movement now called the New Apostolic Reformation, emphasizing the route from spiritual power (especially over demons, which they found everywhere) to political power. Their prophets predicted the 2016 election victory of Trump as early as 2008, and when this crescendo of “prophecies” was crowned with his implausible victory, these Christians and their prophets suddenly were thrust into the limelight.

Paula White, adviser to Trump, led a parade of Pentecostal prophets and apostles into the center of power, and there they predicted a second presidential victory. When it did not happen, they claimed fraud, theft and the judgment of God. If God declared a victory for Trump, then any defeat must be the work of nefarious foes, and it was this mantra that Trump embraced and asserted in courts and county seats all over the country.

“These three movements, like streams flowing into a river, have poured their energies and imagination into a political ideology we call Christian nationalism.”

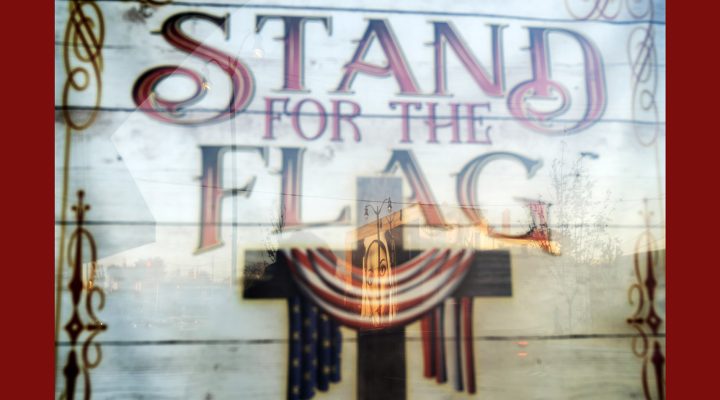

These three movements, like streams flowing into a river, have poured their energies and imagination into a political ideology we call Christian nationalism. “America is a Christian nation,” they claim, “or ought to be, and we intend to make sure it is!” By which they mean occupying places of power so as to influence public policy and even international affairs.

Certainly, all people, including these Christians, have a constitutional right to vote and serve the public on all levels of government. To be honest, I welcome people of faith to places of influence and power. I like it when they kneel in prayer and stand to sing “Amazing Grace.”

But what these Christian nationalists mean by “Christian nation” scares a lot of people, including me. Even as a Christian pastor, I fear the Christian nation they envision: One that values power more than love, dominion more than service, exclusion more than inclusion.

I suspect many of you do as well.

Dwight A. Moody is an author, minister, scholar and host of the media site The Meeting House.

Related articles:

Two viruses threaten the life of the Southern Baptist Convention: Male hierarchy and dominion theology | Opinion by Ellis Orozco

Angels from Africa: Reckoning with the New Apostolic Reformation | Analysis by Alan Bean

Why Iran’s ‘morality police’ might seem like a good idea to some American evangelicals | Analysis by Rodney Kennedy