I’m not an expert on Critical Race Theory, and neither are you. So let’s all stop pretending we know so much more than we do.

This term, which refers to an academic construct that originated in law schools, has become the tagline for our painful national conversation over the past two years about race and slavery and American history. All sorts of people — from parents to pastors to politicians — are blathering on about Critical Race Theory as if they had degrees from Harvard Law.

Mark Wingfield

But most of us don’t, and the vast majority of us don’t know what we’re talking about. Which is exactly what Christopher Rufo wants. He’s the filmmaker and activist responsible for getting Donald Trump’s ear on this issue and sounding a six-alarm fire with less than pure motives.

‘Driving up negative perceptions’

“We have successfully frozen their brand — ‘critical race theory’ — into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category,” Rufo wrote on Twitter in March. “The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’ We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.”

These tweets were reported in a news story about Critical Race Theory in the Washington Post June 21. The Post reporters interviewed Rufo for their story and quoted him as explaining: “If you want to see public policy outcomes, you have to run a public persuasion campaign. … I basically took that body of criticism, I paired it with breaking news stories that were shocking and explicit and horrifying and made it political. Turned it into a salient political issue with a clear villain.”

Rufo, whose entire career right now appears to relate to critiquing Critical Race Theory — check out his Twitter feed and fundraising appeals if you don’t believe me — didn’t like the Post story at all and immediately went on the defensive, calling the reporters “hacks.” The conservative publication The Federalist jumped to his defense as well. But as so often happens in cases like these, the criticisms of the Post story that required correction or clarification were not the heart of the story.

“Rufo proudly takes up the mantle of being one of the nation’s foremost critics of Critical Race Theory.”

The fact that the Post could draw a direct line from Rufo to then-President Donald Trump’s sudden declaration against Critical Race Theory and diversity training is not disputed. In fact, Rufo proudly takes up the mantle of being one of the nation’s foremost critics of Critical Race Theory.

On his own website, Rufo states: “My investigative reporting recently led President Trump to issue an executive order banning critical race theory from the federal government.”

How the SBC was early to the conversation

It’s a short hop from Rufo to Trump to the Southern Baptist Convention, which for two years now has been embroiled in a debate over Critical Race Theory as perhaps the greatest threat to all that is good and godly. Ultra-conservatives in the already conservative world of the SBC have been pushing — so far unsuccessfully — for an explicit rejection of Critical Race Theory by name.

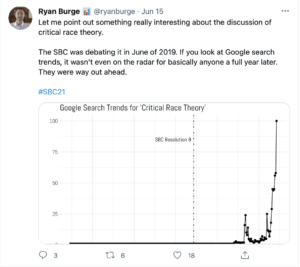

Of note, however, is that the SBC was talking about Critical Race Theory a full year ahead of it being on Trump’s radar. Sociologist Ryan Burge has documented that when messengers to the SBC annual meeting in June 2019 were debating the issue — ultimately passing a contested resolution that demanded the Bible be used as superior to any construct such as Critical Race Theory — the term was hardly showing up on Google searches.

Of note, however, is that the SBC was talking about Critical Race Theory a full year ahead of it being on Trump’s radar. Sociologist Ryan Burge has documented that when messengers to the SBC annual meeting in June 2019 were debating the issue — ultimately passing a contested resolution that demanded the Bible be used as superior to any construct such as Critical Race Theory — the term was hardly showing up on Google searches.

How did the SBC get turned on to talking about Critical Race Theory so early?

One possible answer is John MacArthur, the evangelical (but not Southern Baptist) California pastor, seminary leader, author and speaker best known these days for his year-long battle with the State of California over COVID-19 restrictions on indoor worship. MacArthur has a huge following among conservative Southern Baptists and especially Southern Baptist Calvinists.

John MacArthur and ‘The Dallas Statement’

A full year before the SBC resolution on Critical Race Theory, MacArthur and others — including some SBC figures — drafted a document called the “Statement on Social Justice and the Gospel,” or just “The Dallas Statement.” That document, which now stands alongside a half dozen other doctrinal manifestoes evangelicals have put forth in recent years, decries a perceived threat of orthodox Christianity being influenced by the “social gospel.”

Such a liberal idea as a social gospel is creating “an onslaught of dangerous and false teachings that threaten the gospel, misrepresent Scripture, and lead people away from the grace of God in Jesus Christ,” it says. (By the way, have they not read the Gospels?)

This statement was drafted in Dallas on June 19, 2018, at a meeting attended by MacArthur and organized by Josh Buice, a Georgia Southern Baptist pastor who is part of a network of SBC Calvinists called Founders Ministries. The president of Founders Ministries, Tom Ascol, wrote the first draft of the statement.

The 2019 SBC resolution

Ascol played a key role in both the 2019 and 2021 SBC annual meetings where the issue of Critical Race Theory was addressed in resolutions. In 2019, the SBC Resolutions Committee received a suggested resolution from Stephen Feinstein, a pastor from Victorville, Calif. The committee, as it often does, reworked that draft and presented to the convention their own version of a resolution on Critical Race Theory.

Ascol recounts that he was contacted by Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, about attempting to amend the committee’s resolution on the floor of the convention.

Ascol explains the problem thus: “The original resolution clearly denounced intersectionality and Critical Race Theory as they are typically understood, thus warning Christians against them. The revised version said that critical theory and intersectionality are mere tools that could be used in ways subordinate to Scripture.”

When Ascol attempted to amend the committee’s resolution to make it more specific in condemning Critical Race Theory, the chair of the Resolutions Committee, Curtis Woods, said the committee was not in favor of the amendments: “It is our aspiration in this resolution simply to say that Critical Race Theory and intersectionality are simply analytical tools. They are meant to be used as tools, not as a worldview.”

“And therein lies the dividing line between the ultra-conservatives in the SBC and the plain-old conservatives in the SBC.”

And therein lies the dividing line between the ultra-conservatives in the SBC and the plain-old conservatives in the SBC: The most conservative see Critical Race Theory as a worldview that is a direct threat to the gospel itself; the less conservative see Critical Race Theory as a tool that has some appropriate applications and is not inherently evil.

The Resolutions Committee won the day, but the backlash from the ultra-conservative wing of the SBC came fast and furious. Thus, Ascol was one of the leaders of an unsuccessful effort at the 2021 annual meeting to rescind the 2019 resolution — a key objective of Founders Ministries and a new group called the Conservative Baptist Network.

Expanding the conversation

The SBC’s original foray into denouncing Critical Race Theory happened a full year before Rufo influenced Trump and the three-word label spiked on Google searches. And heading into this year’s SBC annual meeting, Feinstein told Religion News Service he wishes he never had submitted the 2019 resolution that was edited and created such a furor.

However, five months after the 2019 resolution was adopted, Feinstein wrote a thread on Twitter explaining his alarm about Critical Race Theory and what influenced him to submit that resolution in the first place.

“I was seeking to provide a basis of unity between evangelicals that signed the social justice statement (the MacArthur document) & the SBC leaders that did not sign it.”

“When I first proposed my version of the resolution, I was seeking to provide a basis of unity between evangelicals that signed the social justice statement (the MacArthur document) & the SBC leaders that did not sign it. We could still show we all oppose Marxist ideologies and frameworks that attempt to undermine the gospel. Perhaps due to naivete, I did not expect the massive controversy that followed.”

Thus, in a short line of succession, MacArthur’s influence on a group of SBC pastors led one pastor to propose an SBC resolution against Critical Race Theory, which ignited a firestorm and raised the profile of the debate, leading eventually to the White House and the Trump bully pulpit.

Tweeting in December 2019, Feinstein said his original disappointment about creating division through the resolution had given way to happiness that the topic is now in the public’s mind.

“No one knew what (Critical Race Theory) was back in June,” he tweeted. “But not anymore. Because of Resolution 9, people have been talking about (it) for 6 months. It’s been tweeted; it’s been covered repeatedly on podcasts; … Honestly, this is great. This is what needed to happen.”

Feinstein shares a view with Rufo and Ascol and other vocal critics of Critical Race Theory, believing it is more than a theory but a dangerous worldview.

SBC as bellwether for national politics

I’ve argued before that what happens in the SBC is a bellwether for national politics in the United States. The SBC’s “conservative resurgence” paralleled the Reagan Revolution, and that movement’s co-leader, Paige Patterson, foreshadowed Donald Trump.

“I’ve argued before that what happens in the SBC is a bellwether for national politics in the United States.”

Once again, the SBC set the stage for a contentious national conversation — this time about race and our national history of racism. Which is something the SBC is well-qualified to warn about, having been birthed to give cover to a slaveholder who wanted to be a foreign missionary without repenting of the sin of owning other humans.

And remember Rufo, the activist who influenced Trump and has made a cottage industry out of scaring people about Critical Race Theory? His schtick comes right out of the SBC “conservative resurgence” playbook: Take a word or a term, make people afraid of it, knowing they don’t understand it, and use that as a rallying cry to your pet cause.

That’s exactly what Patterson and his compatriot Paul Pressler did to capture control of the SBC. Their rallying cry was “biblical inerrancy” as the necessary cure for creeping liberalism in seminaries and agencies. It’s a safe bet to guess that Southern Baptists in 1979 knew as little of the ins and outs of “inerrancy” as Americans know today about Critical Race Theory.

Learn a lesson from Professor Harold Hill

I’m not an expert on Critical Race Theory, and neither are you. But I do know this: It’s a lot easier to avoid talking about a difficult and complex issue like systemic racism if you can throw up a scary-sounding label and convince people that’s the real threat.

At the end of the day, we need to listen to those whose life experiences have been shaped not just by theories but by laws and practices that are indeed critical of racial differences.

Remember Professor Harold Hill in “The Music Man”? He warned all the parents about the dangers of playing pool in order to convince them to buy musical instruments their kids didn’t know how to play and uniforms they didn’t need.

We do indeed have trouble right here in River City, friends, but it’s not Critical Race Theory. It’s pastors and politicians and parents trying to sell us a scary theory they can’t even explain.

Mark Wingfield serves as executive director and publisher of Baptist News Global.

Related articles:

Southern Baptists are still obsessed with Critical Race Theory | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

White hysteria, Critical Race Theory, and eyes that dare not see | Opinion by David Gushee

It’s not just the SBC banning Critical Race Theory; now state legislatures are joining the fight

Could you win a quiz show by defining ‘Critical Race Theory’? | Analysis by Mark Wingfield