According to an investigative report released earlier this month, deceased celebrity evangelist Ravi Zacharias abused multiple women with “sexting, unwanted touching, spiritual abuse and rape.” The evidence is overwhelming. The details are stark and nauseating.

Many have described the report as “shocking.” But as someone who has spent 16 years watching hundreds of similar clergy abuse cases unfold in the Southern Baptist Convention, I am far beyond the capacity for shock.

The board of Ravi Zacharias International Ministries issued a statement in which they acknowledged that their failures had “allowed tremendous pain to continue,” including specifically their “failure to commission an independent investigation” in 2017 when allegations first arose.

Christa Brown

The SBC has a similar long-enduring failure — the failure to implement a proactive accountability system that facilitates immediate independent investigation of clergy sex abuse reports. It, too, is a failure that has “allowed tremendous pain to continue.”

Without the objectivity, transparency, expertise and credibility that an independent process can provide, further wreckage is wrought in the lives of clergy abuse survivors who seek to report their perpetrators within the faith community. Told that they must go to the local church, Baptist abuse survivors become like bloody sheep walking back into the den of the wolf.

The savagery is predictable. Almost invariably, survivors crawl away from the experience saying that the faith community itself caused more harm than the molesting minister, as so many respond with complicity instead of care, silence instead of justice, and intimidation instead of transparency. This was my personal experience as well.

This is why, 15 years ago, advocates like me began urging the SBC to create an independent review board so as to provide a designated safe place for survivors to report clergy sex abuse. We also reasoned that a specialized independent board could provide the necessary objectivity for responsibly assessing abuse reports (especially those that cannot be criminally prosecuted, which is most), and could then provide local churches with a database resource for obtaining reliable information about credibly accused pastors.

There never was anything radical about this request. Outsiders are essential to any organizational system of accountability.

“We have seen that ordinary human beings have a hard time seeing clearly when abuse allegations arise on home turf.”

Over and over, in countless SBC cases and in the Ravi Zacharias tragedy, we have seen that ordinary human beings have a hard time seeing clearly when abuse allegations arise on home turf. Inclined to gravitate toward narratives that feel more comfortable, people often lapse into denial and self-protection. Unspoken motivations of self-advancement and paycheck preservation may also arise, fostering blind-eyed, collusive responses centering on personal loyalty and institutional protection.

Moreover, a pastor-predator typically grooms not only his victims but also his congregation, deliberately cultivating those around him to believe in the pastor’s God-called righteousness so that he can more readily commit his grotesqueries with impunity.

When you combine all this — the predator’s cunning with the human tendency toward denial — and perhaps especially when you wrap it in religion, the result is that those close to the pastor are usually incapable of effectively imposing accountability. More often, they will make themselves complicit, causing exponentially greater harm to the abused, who is then further traumatized by the faith community’s institutional betrayal.

Consider how easily Ravi Zacharias deceived those around him. Columnist David French reported that the Christian and Missionary Alliance, which had ordained him, conducted “a thorough and complete investigation.” Similarly, RZIM’s board of directors said it “looked into everything.” Both insisted there was no wrongdoing and readily cleared him.

It was only after significant details were leaked into the public square that media pressure prodded RZIM into commissioning an independent investigation. And finally, the harrowing truth of Zacharias’ serial predation was pulled forth into the light.

Although most Southern Baptist preacher-predators are not celebrities like Zacharias, their victims’ wounds are no less grievous.

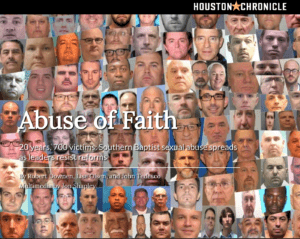

The 2019 Abuse of Faith series documented more than 700 people who had reported being sexually abused by leaders and clergy within the SBC. Almost all them were children at the time of the abuse.

The 2019 Abuse of Faith series documented more than 700 people who had reported being sexually abused by leaders and clergy within the SBC. Almost all them were children at the time of the abuse.

Advocates and religious leaders know this 700 number likely accounts for “only a fraction of the actual amount of abuse that occurs in SBC churches.” Many survivors hold abuse stories that would not have been counted because they never were previously documented, and many other stories fell outside the series’ 20-year investigative window. Additionally, Abuse of Faith did not attempt to address the abuse of adult congregants. So the true number of victims is certainly much larger.

This month marks two years since Abuse of Faith was published, and despite the horrific patterns of predation it showed, the SBC’s response has been anemic. The SBC seems uninterested in even assessing the scope of the problem, and institutionally, little has changed. The same systemic oversight failures persist.

Although a new Credentials Committee process was trotted out, it was deeply flawed from the get-go, apparently designed less as a process to hold abusers and enablers accountable and more as a process to institutionally save face after media already has done the work of exposing them. “It is essentially impotent,” said prominent victim advocate Rachael Denhollander.

In the immediate aftermath of the Abuse of Faith series, some Southern Baptist leaders voiced their support for an independent investigation. Al Mohler wrote that an independent, third-party investigation was “the only credible avenue” and said, “No Christian body, church or denomination can investigate itself.”

He was right about that, but here we are two years later and the SBC still has no institutional process for independent investigation of clergy sex abuse reports.

Now some Southern Baptist leaders have praised the independent investigation commissioned by RZIM. But the irony of this is not lost on survivors. It appears SBC leaders applaud independent investigation for others but resist it for themselves.

The SBC needs to reckon with the full scale of failures within the entirety of its own faith group, and the way to do that is with a cooperatively funded independent commission that will proactively hear from all survivors who want to report any clergy abuse that occurred in SBC-affiliated churches and entities.

“It takes independent investigation to bring truth to light.”

This is the lesson of the Ravi Zacharias tragedy. It takes independent investigation to bring truth to light, not only truth about particular abuse allegations but also truth about the patterns of institutional enablement.

Truth can bring seismic upheaval, as it has for RZIM, which now has pledged itself to organizational reform “to make sure nothing like this happens again” and to “a process of care, justice and restitution” for those who were victimized.

Similarly, the SBC must take a hard look in the mirror and see the ways that its own institutional structures enable clergy abuse, stymie justice and inflict grievous additional wounds. That “hard look” can only be had through a long process of independent investigation.

Christa Brown, a retired appellate attorney, is the author of This Little Light: Beyond a Baptist Preacher Predator and his Gang. She previously served on the board of directors for the Survivors’ Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), and she currently serves on the board of advisors for the Child-Friendly Faith Project.