One of the biggest lies perpetuated in modern American Christianity is about the end times. Just by paying attention to popular culture and conversation, you would assume that the “Left Behind” theology is the most accepted — and maybe the only — way to think of the end times. That estimation, however, would be wrong.

Premillennial dispensationalism, the exact name for the “Left Behind” theology, always has been and remains a minority view among global Christians. And even though it was first espoused in England, this theology took root mainly in America.

Furthermore, neither the early church leaders nor the majority of Christian leaders throughout history would have known about premillennial dispensationalism because it is an invention of the mid-19th century.

How, then, did a fringe theological idea gain such prominence that it dominates discussion about the end times across America? The answer, in a word, is marketing.

From England to America

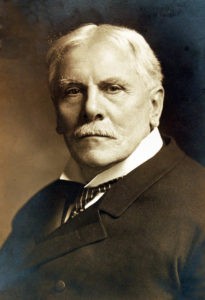

John Nelson Darby

John Nelson Darby was an Anglican minister in England, born in 1800. He went on to become a founder of the Plymouth Brethren and is the person credited with first fully articulating ideas now known as dispensationalism and a pre-tribulation rapture. (More on what that means in a moment.) From about 1831 until his death in 1882, Darby wrote and lectured about his views, which were rejected by the Anglican Church but took root in certain other segments, mainly parts of the Presbyterian movement and eventually among Baptists.

C.I. Scofield

Darby in turn influenced an American lawyer-turned pastor, Cyrus Ingerson Scofield, who led quite an interesting and tumultuous life before converting to Christianity somewhere in the late 19th century. By 1883, Scofield, then age 40, was ordained as a Congregationalist minister and sent to Dallas to lead a small mission church called First Congregational Church.

An interesting side note: That church, later renamed in his memory as Scofield Memorial Church, now exists within walking distance of my home in Dallas. However, I came under the influence of Scofield long before I ever moved to Dallas.

The Scofield Reference Bible

Growing up in a conservative Southern Baptist church in central Oklahoma, I was given as a teenager my own copy of the Scofield Reference Bible. This was the standard-issue, gold-standard Bible for faithful Christians in my orbit to use, not only because of its premillennial dispensationalist theology but because of its clever inclusion of a running series of notes throughout the text. This book is Bible and commentary packaged together in one product as though they are the same.

A page from the Scofield Reference Bible, showing Scofield’s notes at the bottom.

And, indeed, that was the promise and the problem. The Scofield Reference Bible, which first was published in 1909, melded premillennial dispensationalist theology with the King James Version of the Bible so seamlessly that impressionable teenagers like me assumed both parts were “authorized.”

While Catholics and most mainline Christian denominations were not pulled into Scofield’s orbit, many Baptists and the emerging group of nondenominational churches were. Another person influenced by Scofield was the American evangelist Billy Graham. In fact, there is a direct line of connection from Graham to the “Left Behind” books and films.

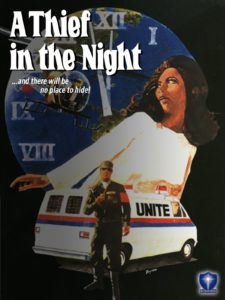

‘A Thief in the Night’

Back in the 1970s, when we had just three or four channels of TV available and you had to go to a theater to see a movie, it was popular for religious films to be disseminated through churches, where people would gather in sanctuaries or fellowship halls to watch films on portable screens. The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association had an entire division dedicated to producing and distributing these films. And one of their most popular was a film titled “A Thief in the Night.”

I remember as a young teenager watching this film at church and having nightmares afterward sparked by fear of being left behind in the rapture. The film’s haunting theme also became popular in churches and on earlier Christian radio stations: “I Wish We’d All Been Ready,” by Larry Norman.

Here’s a quick summary of the movie’s plot: Patty Myers considers herself a Christian because she attends church. But we soon learn that neither she nor the pastor of her church are true believers because they get left behind at the rapture. Patty awakens one morning to discover her husband vanished — along with millions of others worldwide. Then she experiences a classic dispensationalist interpretation of the book of Revelation, as the United Nations establishes a global government that requires all adherents to receive a mark — the Mark of the Beast — or be arrested.

Here’s a quick summary of the movie’s plot: Patty Myers considers herself a Christian because she attends church. But we soon learn that neither she nor the pastor of her church are true believers because they get left behind at the rapture. Patty awakens one morning to discover her husband vanished — along with millions of others worldwide. Then she experiences a classic dispensationalist interpretation of the book of Revelation, as the United Nations establishes a global government that requires all adherents to receive a mark — the Mark of the Beast — or be arrested.

In case it’s not already obvious, you can see how this film, released 50 years ago, plays into several evangelical Christian cultural stereotypes about evangelism, culture and politics. Even the pastor of Patty’s church is not a true believer, so everyone should be wary of the certainty of their salvation. That’s the message I grew up hearing, which is why I was baptized twice — once as a 9-year-old and once as a 15-year-old. As a teenager, I became convinced I had not been truly saved at age 9 and needed a do-over.

But also note the role the United Nations plays in this film, becoming the evil agent of the antichrist. Understand that in the 1970s, belief that the United Nations was part of an anti-Christian, anti-democratic conspiracy was indeed a fringe belief. And yet, here that conspiracy is given a starring role in a Billy Graham film. There’s a direct line from there to the chants of “America First” in our times.

Premillennial dispensationalism hits the big time

To recap, we’ve gone now from John Nelson Darby in the mid-19th century to C.I. Scofield in the late 19th century to Billy Graham in the mid-20th century — there are other points along the way that I’ve left out for brevity — and that sets the stage for premillennial dispensationalism’s acceleration to the big leagues.

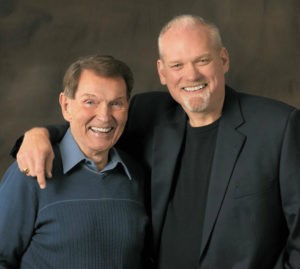

Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins

“A Thief in the Night” inspired evangelist Tim LaHaye and writer Jerry Jenkins to adapt this theological view into the format of a popular novel. Thus, in 1995 they published the first of the “Left Behind” series. This was the theological equivalent of placing an explosive device on a rocket — vastly extending the range and influence of an otherwise still minority and biblically suspect view.

The novels — 16 in all — captured readers’ attention and made their way to the bestseller lists. More than 65 million copies have been sold. What LaHaye and Jenkins did was to take a complicated theological system and write it into a series of action thrillers as though it was generally accepted wisdom straight from God. In this way, the authors weaponized their obscure theology by making it a plot device in a series of fast-paced, easy-to-read novels.

Jerry Falwell lauded the first book in the series: “In terms of its impact on Christianity, it’s probably greater than that of any other book in modern times, outside the Bible.” Critics were not so kind, mocking both the sensationalized theology and pulp-fiction writing. But again, the books sold millions.

And then came the movies, four in total, that further popularized the theology and made it appear mainstream.

To summarize, “Left Behind” did for premillennial dispensationalism what the Mormon Tabernacle Choir did for Mormonism. It gave a public face to an otherwise obscure and minority theological view and made it appear to be as normal as mainstream Christianity.

What’s wrong with Left Behind?

And by now, some of you are wondering what’s so wrong about premillennial dispensationalism and the “Left Behind” series. Why have I just expended more than 1,000 words giving the history of this viewpoint?

The short answer is that premillennial dispensationalism is, itself, a lie. It is a tortured misreading of the biblical text that appeals to fear, racism and jingoism as substitutes for wrestling with the hard questions of Scripture. It is a system that offers too-easy answers to complex life questions and that thrives on appearing to have a secret decoder ring that no one else has.

“It is a tortured misreading of the biblical text that appeals to fear, racism and jingoism as substitutes for wrestling with the hard questions of Scripture.”

Dispensationalism — like Calvinism, from which it is an offshoot — pretends to have all the answers and the only right answers to some of life’s most difficult questions. Its adherents give no notice that other devout Christians understand the Bible and the end-times prophecies differently. And it makes huge doctrinal leaps from words and ideas that don’t appear anywhere in the biblical text — chief among those being the word “rapture.”

Yes, I understand that not all biblical doctrines are spelled out by name in the Bible — the doctrine of the Trinity being a chief example of a key teaching that is inferred from Scripture but not identified by name anywhere in Scripture. I would argue, however, that the component parts of a doctrine of the Trinity are much more visibly present in Scripture than are the ideas of dispensationalism.

Understanding the challenges of Revelation

First, understand that Revelation is unique among biblical books because of its style. It is the only book in the Bible written in an apocalyptic style. This was a style of writing popular among Jewish audiences between 200 B.C. and 100 A.D.

Apocalyptic literature is not meant to be read literally. And this is a dominant failure of premillennialism, forcing a literal reading on a poetic text. It’s like reading a spreadsheet and trying to understand it as a novel. That’s not its purpose.

“It’s like reading a spreadsheet and trying to understand it as a novel.”

Further, premillennialists want to see symbolism behind parts of Revelation but not others; for example, reading the vivid images such as beasts and dragons as symbolic but insisting that numbers such as seven and 1,000 must be literally understood.

Among the things that argue against a literal interpretation of Revelation — and offer a clear clue that it is apocalyptic — is the repeated use of the number seven. There are seven churches, seven seals, seven bowls, seven trumpets. This is not coincidental. Seven is a number that in apocalyptic writing conveys completeness. It is a code more than a literal number. Likewise, multiples of 12 convey another meaning, and references to 1,000 years most likely symbolize a long time more than an exact number of years.

Most important, we must remember that Revelation was written to a specific group of people at a specific time for a specific reason. Good biblical interpretation requires that we first understand this context before attempting to transfer the teaching to modern times.

Revelation’s purpose

If you believe the “Left Behind” hype, you’d think Revelation was written to give us modern-day Christians a blueprint to the end times, sort of like Nicholas Cage putting the pieces together in “American Treasure.”

Yet seen in its proper context, we may understand the primary purpose of Revelation as to encourage the early church amidst intense persecution. We know that Revelation was written during a time of persecution of the early church. We just don’t know which exact time of persecution spawned it. Most scholars agree that the book describes the imperial persecutions of the Roman emperors. Altogether, there were 10 emperors believed to have persecuted Christians, but only two of them did so within John’s lifetime. Those are Nero, who reigned from 54 A.D. to 68, and Domitian, who reigned from 81 A.D. to 96.

How you understand the timing of the book’s writing is a key influence on how you interpret the book. And how you interpret a few key words also shapes your view. Among those key words is the meaning of the “thousand years” referenced in chapter 20. In all the Bible, only this one chapter of Revelation mentions the thousand-year reign of believers with Christ, and yet premillennialism builds an entire theology out of this.

Scores of books have been written to explain the various ways to understand Revelation and the end-times prophecies. We’ll not take time here to expand on them, just to quickly name them as premillennialism, postmillennialism and amillenialism. All three offer distinct advantages and disadvantages to interpretation. But we, seeing through a glass darkly as the Apostle Paul writes, do not have enough information to make a judgment.

And that is the source of the biggest lie perpetuated by premillennial dispensationalism and “Left Behind”: The assertion that this alone is the only valid view.

Mark Wingfield serves as executive director and publisher of Baptist News Global.

Related articles:

Christians should study Revelation (but not for the reason you may think) | Opinion by Corey Fields

From Romans to Revelation: How Christians began to stand against the Emperor | Opinion by David Jordan

Apocalyptic obsession that inspired ‘Left Behind’ series also fueling Trump support, ministers say

I wish we’d all been ready | Opinion by Susan Shaw