Most of us think of “the disabled” as someone other than ourselves. But that is unrealistic, according to a New Testament scholar who focuses on the issues of gender, disability, eschatology and suffering.

Meghan Henning, author of Hell Hath No Fury: Gender, Disability, and the Invention of Damned Bodies in Early Christian Literature, recently visited Wingate University for a presentation about gender, disability and ancient hellscapes.

For centuries, disability has been scandalized by society as we think of it as something different from the norm. This becomes a theological issue when we imagine the non-normative body as suffering, making it the baseline for conceptions of punishment that indicate an individual’s moral value and ethical performance.

However, when we look at what types of bodies we consider non-normative, we learn they may actually be more relatable than we think.

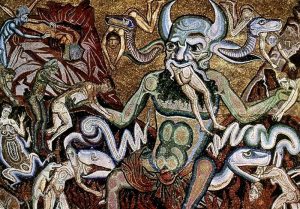

A 13th-century depiction of Hell, from the ceiling of the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence, Italy.

In her presentation, Henning outlined the ways in which feminine and disabled bodies were subjects of torture and punishment in early Christian conceptions of hell. She noted that women and disabled persons suffered not only marginalization in life on earth, but their bodies were subjected to gross, painful and degrading punishments in the afterlife.

Early Christian hellscapes involved sour breastmilk, the feminizing of male bodies through penetration and lactation and the disabling of able-bodied persons all as means of punishment. In other words, the normative bodies of able-bodied, masculine-presenting men were punished in conceptions of hell by becoming the non-normative: feminine and disabled.

To become these two things was, in the early Christian imagination, equivalent to eternal suffering.

One particularly striking punishment Henning discussed involved worms penetrating and coming back out of the bodies of sinners. This punishment was scary for early Christian men because it feminized their body through suffering, she noted.

Another punishment she described included women and men who practiced almsgiving dishonestly being made blind and deaf, then pushed together and subjected to eternal burning atop fiery coals.

“There was no neutral body, but rather a body that was good and normative, and a body that was assigned to suffering.”

These punishments offer a clear representation of the value ancient society placed on diverse bodies. There was no neutral body, but rather a body that was good and normative, and a body that was assigned to suffering. And for early Christians, this binary is clearly split between the bodies of men and the bodies of women and disabled persons.

But in her critique of these assignments, Henning noted something that stuck with me: “At some point in their lives, everybody will become disabled.”

This statement makes an essential point for non-disabled listeners. Every person is currently or at some point in their life will be affected by disability justice.

She was speaking against the categorical notion that a person is either disabled or they are not. This is how we often view ourselves. However, Henning explained that as we age, which is a natural and inevitable part of life, we all lose some of our abilities to function as would an able-bodied individual.

We become hard of hearing, our vision decays, it is more difficult to move around, our memory may worsen, or we may become disabled as a result of an accident or a disease.

She also made this connection during her Q&A period: That today, many men who develop memory disorders or other disabilities for which they require care describe themselves as feeling effeminate. This often is coupled with a mental health decline. The notion that they are disabled, and thus living in a no longer normative body, makes them feel like they are no longer a man.

“Many men who develop memory disorders or other disabilities for which they require care describe themselves as feeling effeminate.”

Thus, the ancient assignment of the bodies of women to suffering, and the feminine equivalency to disability, has translated into modern conceptions of body image. To live in a body that is not able-bodied, masculine and male means you live in a body that is less valuable, as femininity and disability are perpetually assigned to suffering.

Henning’s point, that we are all either currently or will eventually become disabled, puts into perspective the impact these feelings have on us.

Of course, you do not have to be currently disabled to understand disability studies, engage in discourse about disability justice or empathize with the disabled community. There are many able-bodied and neurotypical people who do.

But when you know that issues such as a lack of wheelchair-accessible ramps and elevators, the small text on posters, papers or presentations, the lack of reliable captions, classrooms catered to neurotypical learning styles, and many other things will one day make life harder for you, disability justice should become personal.

There becomes no “us” and “them” when we talk about disability.

We must begin to understand the disabled body as neutral. It is not a feminized body that is assigned to suffering; It is simply a body that exists in the world. And that body deserves the same amount of accessibility as any other.

Mallory Challis

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves this semester as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.