Where are the women in American evangelicalism?

The first answer that comes to mind might be “everywhere.” Women form the majority of evangelical congregations and can be found leading music, participating in small groups, teaching children and planning events, among other activities.

Melody Maxwell

And yet it’s worth a closer look. In many evangelical congregations, women are forbidden from holding leadership roles such as senior pastor. The ideology of complementarianism asserts that while women and men are equal in creation, they are distinct in function. Men are to serve as leaders of church and home; women are to support and submit to them. This way of thinking, which advocates “biblical womanhood,” is based on one interpretation of passages from the New Testament. Because of its prevalence, more women almost certainly can be found on nursery duty than behind pulpits each week in American evangelical churches.

While the vocabulary of “complementarianism” and “biblical womanhood” is new, the concepts are not. Most American evangelicals have long believed that men should lead churches. This view has been based both on cultural norms and on conservative biblical interpretation. After the Industrial Revolution, when many men went to work in factories while women stayed home, the idea of “separate spheres” predominated.

This was especially the case in the Southern Baptist Convention. Reflecting its conservative Southern context, the SBC maintained strict gender roles.

“The vocabulary of ‘complementarianism’ and ‘biblical womanhood’ is new, the concepts are not.”

Southern Baptist leader John Broadus answered the question, “Should women speak in mixed public assemblies?” with a definitive “no” in 1889. The year before, when Southern Baptist women formed Woman’s Missionary Union, they assured male leaders that they desired only to be supportive, not independent as women of some other denominations were. Such thinking, advanced by the world’s largest organization for Protestant women, shaped the views of generations of Southern Baptist women and, in turn, those of their evangelical neighbors and friends.

Some American women found their voices in the Great Awakenings. But as evangelicalism institutionalized, they often were silenced or relegated to speaking to women and children.

The women’s movements of the 20th century stirred conversations about women’s roles among American evangelicals, although most were hesitant to change. Again, Southern Baptists epitomized the conservative views of many evangelicals on this topic. In 1974, Joyce Rogers, wife of influential pastor Adrian Rogers, wrote that “the man would lead; the woman was to be submissive.”

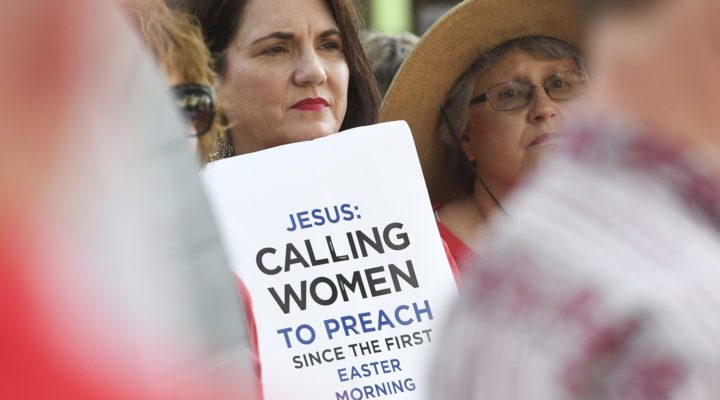

Around the same time, some Southern Baptist women — and men — were rethinking women’s roles. Addie Davis was ordained in 1964, and other women gradually followed her example. SBC agencies held a consultation on women’s roles in 1978, and within a few years, Women in Ministry, SBC (now Baptist Women in Ministry) was organized. Its members believed that earlier interpretations of the Bible had focused on prooftexts instead of the broader themes of the New Testament. They advocated for women’s inclusion and equality in pastoral roles, in seminary classrooms and throughout society.

Within broader American evangelicalism, Christians for Biblical Equality was organized in 1988. It challenged traditional evangelical biblical interpretation and leadership, seeking to empower women in evangelical churches.

“The debate about biblically appropriate gender roles escalated within the evangelical context of the late 20th century.”

Around the same time, the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood was formed. Among other proclamations, it denounced “the emergence of roles for men and women in church leadership that do not conform to biblical teaching but backfire in the crippling of biblically faithful witness.” The debate about biblically appropriate gender roles escalated within the evangelical context of the late 20th century.

The complementarianism of organizations like CBMW remained the default ideology of many evangelicals in the years that followed. Within the SBC, conservatives ousted moderates — such as members of Woman in Ministry, SBC — after a fierce controversy. The denomination affirmed its complementarian stance with the publication of the Baptist Faith & Message 2000, which proclaimed that wives should submit to their husbands and that pastors should be men.

From within this conservative Southern Baptist context arose Bible study author and teacher Beth Moore. Moore emerged in the 1990s, as women’s ministry grew in popularity among American evangelicals. Thousands of women’s groups completed Moore’s studies while also absorbing her affirmation of biblical womanhood. Moore explained that, as appropriate for a complementarian, her husband “wore the cowboy boots” in their family.

Moore’s teachings continued their popularity among evangelical women in the early 21st century. Yet by 2016, Moore’s thinking began to shift. Incredulous at Southern Baptist support for Donald Trump, she began to break ranks with the denomination’s leaders. She and other women also were troubled by the lackluster response to women who alleged they had been abused by Southern Baptist pastors. By 2021, Moore announced she no longer was Southern Baptist. Days later, she apologized for treating complementarianism as “among the matters of first importance.”

Moore is not the only evangelical woman who recently has changed her mind about gender equality. High-profile abuse scandals within evangelical churches have caused others to be wary of the possible consequences of teachings on male headship.

“The rise of the internet and social media has allowed evangelical women to speak directly to their peers.”

In addition, the rise of the internet and social media has allowed evangelical women to speak directly to their peers, no matter whom they are allowed to instruct in local churches. Today, evangelical women can express their thoughts within a few seconds with a tweet, rather than waiting months for their writing to be approved by a denominational periodical. As a result, influential evangelical women have encouraged their audiences to reconsider their understandings of women’s roles. Many have concluded that the Bible advocates gender equality. Interest in this topic is demonstrated by the proliferation of related books, such as A Year of Biblical Womanhood, Jesus Feminist, and The Making of Biblical Womanhood.

Where are the women in American evangelicalism? Some may be found reconsidering their roles in church and home, while not abandoning the core tenets of evangelicalism. A challenge for American evangelicals in the days ahead is to take these women and their views seriously. Evangelicals must not marginalize the concerns of those like Beth Moore as just “women’s issues” stemming from secular movements. They must not pretend they have not heard allegations of abuse or marginalization. Women and men alike must listen to evangelical women’s voices and ask whether God might be speaking through them.

Where are the women in American evangelicalism? My hope is that in the days to come they will be in the pulpit and the boardroom, leading megachurches and country parishes, and boldly proclaiming the word to “mixed audiences” across the United States and beyond.

In order for this to happen, many evangelicals must reconsider how culture and history have influenced their views. They must recognize the God-given potential of women and invite them to serve in positions of influence. This includes intentionally incorporating women into all aspects of church and denominational life, including visible roles in worship services. It might also involve reviewing and recommending books, sermons and podcasts by women and encouraging women and girls to consider ministry vocations. Whatever the specific actions, equality will require deliberate efforts and not just occasional concern.

Where are the women in American evangelicalism? When future historians look back on our time, I hope they recognize a significant change in the roles of and attitudes toward evangelical women beginning in the 2020s. I look forward to the possibility of their discovery that from this time on, women in American evangelicalism truly were everywhere.

Melody Maxwell serves as associate professor of church history and director of the Acadia Centre for Baptist and Anabaptist Studies at Acadia Divinity College in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. She is a graduate of Union University, earned a master of divinity degree from Beeson Divinity School at Samford University, and earned a Ph.D. from the International Baptist Theological Seminary. This article originally was published in the Berkley Center Forum of Georgetown University and is used here by permission.

Related articles:

I knew the truth about women in the Bible, and I stayed silent | Opinion by Beth Allison Barr

Now Beth Moore is taking on patriarchy in the church

Why Beth Moore’s departure from the SBC really matters

Beth Moore and a lost Southern Baptist Convention | Opinion by David Gushee

Is the Beth Moore Effect a feminist awakening? | Analysis by Courtney Pace

Jesus and John Wayne exposes militant masculinity in the age of Trump | Analysis by Alan Bean