To understand the problem of global COVID vaccine inequity, consider these statistics: “We have crossed the figure of 3 billion vaccine doses administered (globally), and still only 0.3% of those have gone to low-income countries. Of the 2.6 billion tests performed globally, less than 4% of those have been administered in Africa. And yet we represent over 17% of the global population.”

Mmamoloko Kubayi

Those are the words of Mmamoloko Kubayi, South Africa’s acting minister of health.

Her concern illustrates why some public health experts believe parts of Africa may not receive access to COVID-19 vaccines until 2023 — while Americans are now rejecting the readily available doses at their disposal.

Kubayi’s fear and agitation are shared by other world leaders, including Ayoade Olatunbosun-Alakija, co-chair of the Africa Union African Vaccine Delivery Alliance for COVID-19.

“As the world races against time in a bid to outrun the coronavirus, it appears the race is staggered in favor of the wealthy nations and the wealthiest people,” she said during a recent online event sponsored by the Africa Health Agenda International Conference. “The media is currently awash with images of world leaders, health workers and vulnerable people getting that long-awaited vaccine jab in their arms …, yet for many of the world’s poorest people, there are no vaccines in the immediate future and similar images from many parts of Africa and Southeast Asia can be quite a while away.”

Ayoade Olatunbosun-Alakija

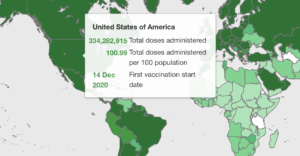

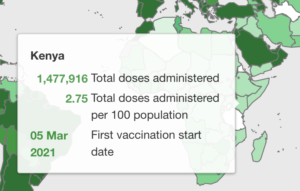

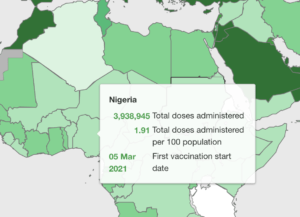

Through the COVAX initiative, more vaccine doses are making it to Africa, but the statistical comparison shows the continued inequity. Nigeria has received 3.92 million doses of vaccine for its population of more than 210 million people, while the United States as recently as May was vaccinating 3 million people per day.

“Where’s the equity in that?” Olatunbosun-Alakija asked. “We need to have the conversation about equity. … Until we are all safe, none of us can be safe.”

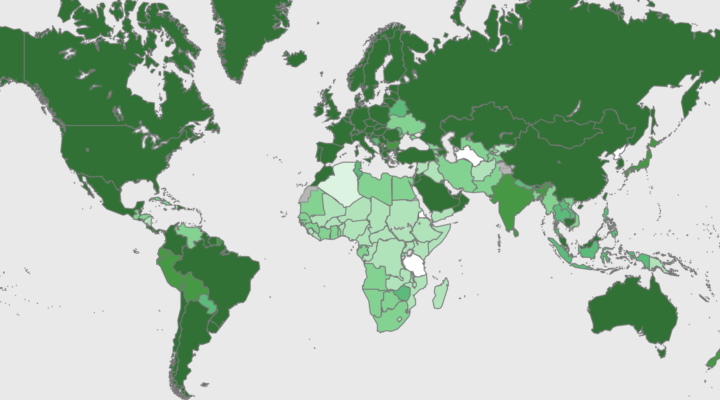

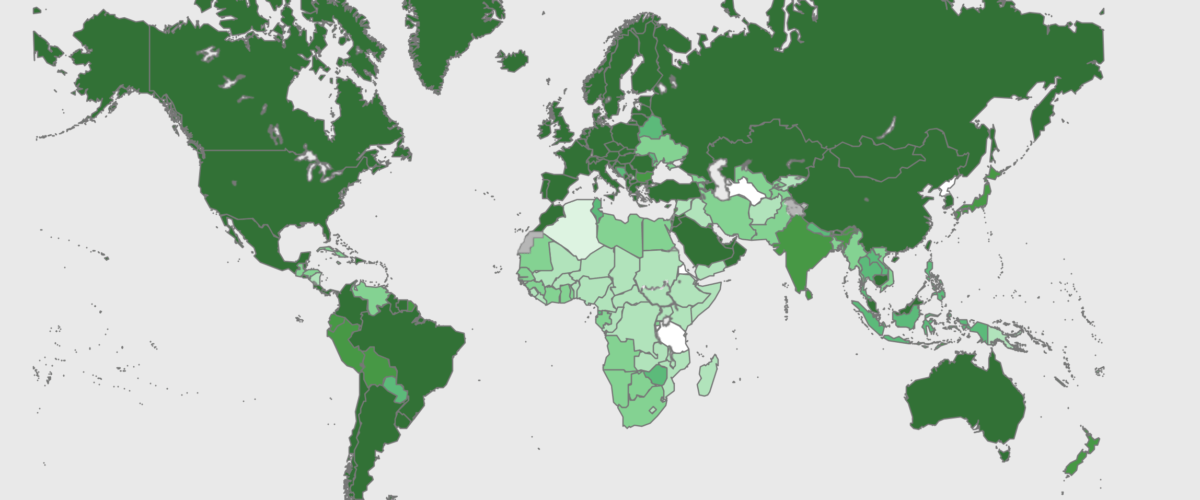

The global data

While her comments were made four months ago, the situation hasn’t yet changed much for the better. The tracking website Our World in Data reports as of July 18 that 26.2% of the world’s population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, with 3.63 billion doses administered globally and 29.73 million being administered each day. Yet only 1% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose.

Many Africans who desire to be vaccinated are unable to because they either cannot afford the cost on their own or they are unable access the free vaccines donated by countries like the U.S. or groups like the World Health Organization and its COVAX initiative. COVAX was launched “to accelerate the development and manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines, and to guarantee fair and equitable access for every country in the world.”

Many Africans who desire to be vaccinated are unable to because they either cannot afford the cost on their own or they are unable access the free vaccines donated by countries like the U.S. or groups like the World Health Organization and its COVAX initiative. COVAX was launched “to accelerate the development and manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines, and to guarantee fair and equitable access for every country in the world.”

Vaccine inequities continue to cause avoidable deaths, Kubayi said, and to slow the defeat of the global pandemic.

The latest data on GAVI, the website of The Vaccine Alliance, showed as of July 15 that more than 119 million COVID-19 vaccines have been shipped to 136 countries, of which 27 are in Africa. These include Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Comoros, Togo, Ethiopia, Malawi, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria.

For example, Nigeria has been allocated 13.6 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, and just shy of 4 million doses have been delivered to the country. And Ethiopia has been allocated 7.6 million doses, of which it has received 2.1 million.

But half of the African continent’s 54 countries are yet to be covered by the COVAX initiative.

Why should Americans care?

This huge gap in the vaccine equity exists despite the Biden administration’s pledge of more than 80 million vaccine doses to about 50 countries, including African and Caribbean nations.

Anna Mouser

Americans and other world citizens who already have access to vaccines should be concerned about the global plight, said Anna Mouser, policy and advocacy lead on vaccines for Wellcome, a global charitable foundation: “The (vaccine) imbalance is shocking, not just because of its moral failings, but also because it will impact our ability to end the pandemic. We know that a global vaccine rollout is essential to get control of the virus, so we need to make that case clear.”

Jeremy Farrar, director of Wellcome, agreed. “The only way to bring the pandemic to a close and improve all our lives is to make the vaccines available to everybody. I would rather vaccinate some people in every country than all people in some countries. Vaccinating a lot of people in a small number of countries will not bring the pandemic to a close and, in fact, it will encourage the development of new variants that may escape those very vaccines.”

Disruption of global travel

This inequity also affects global travel, as vaccination has become a kind of passport to the world. Those unable to access vaccines, therefore, come up against all manner of impediments in their bid to travel from place to place.

In an article for Scientific American, Steven W. Thrasher points out that “borders in some countries are currently being used to determine who does and doesn’t get a vaccine.”

And then in return, those virus-controlled borders limit the ability of some to work, said Judy Stone, an infectious disease specialist and author. “An ongoing, uncontrolled pandemic will wreak further economic havoc as billions are unable to work and travel and risks more virulent mutations emerging.”

“Viruses do not recognize borders. No one is safe until we all are.”

She added: “We must realize that we are all in this together and work together to assure global equity in access to vaccines and medicines. Viruses do not recognize borders. No one is safe until we all are.”

One example of how COVID has become a stumbling block to travelers from Africa is the travel order issued in June by Emirates, the official airline of the United Arab Emirates. The company initially banned passengers from Nigeria and South Africa from traveling to the UAE through its airline. Passengers from the two African countries, along with those from India, the world’s second-most-populous country, previously had been barred by Emirates from entering the country due to COVID concerns.

Emirates later lifted the ban and announced that flights from the three countries would resume June 23, only to reverse shortly thereafter by reintroducing the travel ban. The airline’s website currently says inbound flights from the three countries remain suspended until July 21 of this year.

Faith leaders speak out

As African leaders step up diplomatic appeals to more affluent countries to come to their aid, a coalition of faith leaders in the U.S. is adding its voice to the call for vaccine equity. At an event billed for July 20 in Washington D.C., the religious leaders plan to mourn the lives lost to COVID-19, then call on President Biden and other world leaders to share vaccine recipes and step up efforts to make the COVID vaccines readily available to disadvantaged countries, particularly in the global south.

The faith leaders are expected to urge the U.S. president and Congress to invest $25 billion in a program that would enable the creation of vaccine manufacturing centers and personnel training around the world with the objective of mass-producing the vaccines and making them easily affordable to all people.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

And there are some reasons for hope, according to Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO director general: “There are signs of hope. Countries are starting to share vaccine through COVAX, but we need more and we need them faster. The COVAX Facility Advanced Market Commitment mechanism is fully funded for 2021, but there are still substantial risks in the vaccine supply forecast. The announcement of a new mRNA manufacturing hub in South Africa is a positive step forward, but we need manufacturers to help by sharing know-how and accelerating technology transfer.”

And he added: “While we have progressed in controlling the pandemic, it remains in a very dangerous phase. Our only way out is to support countries in the equitable distribution of PPE, tests, treatments and vaccines.”

Doing so, he said, won’t be “rocket science nor charity. It’s smart public health and in everyone’s best interest.”

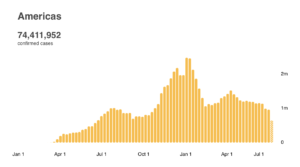

History of COVID infections in the Americas.

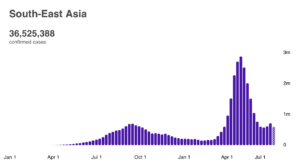

History of COVID infections in Southeast Asia

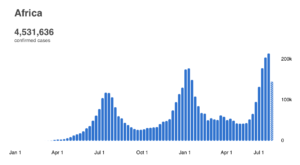

History of COVID infections in Africa

Related articles:

4 in 10 Americans don’t see getting vaccinated as a way to ‘love your neighbor’

Honoring vaccination status is the next step for social justice | Opinion by Amber Cantorna

If you think we’re out of this pandemic, take a look at the rest of the world