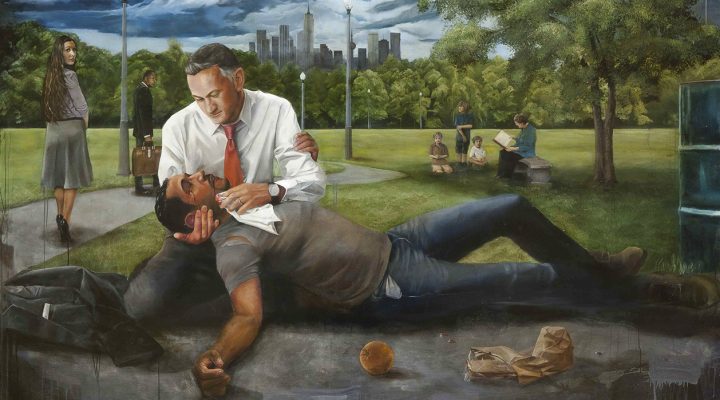

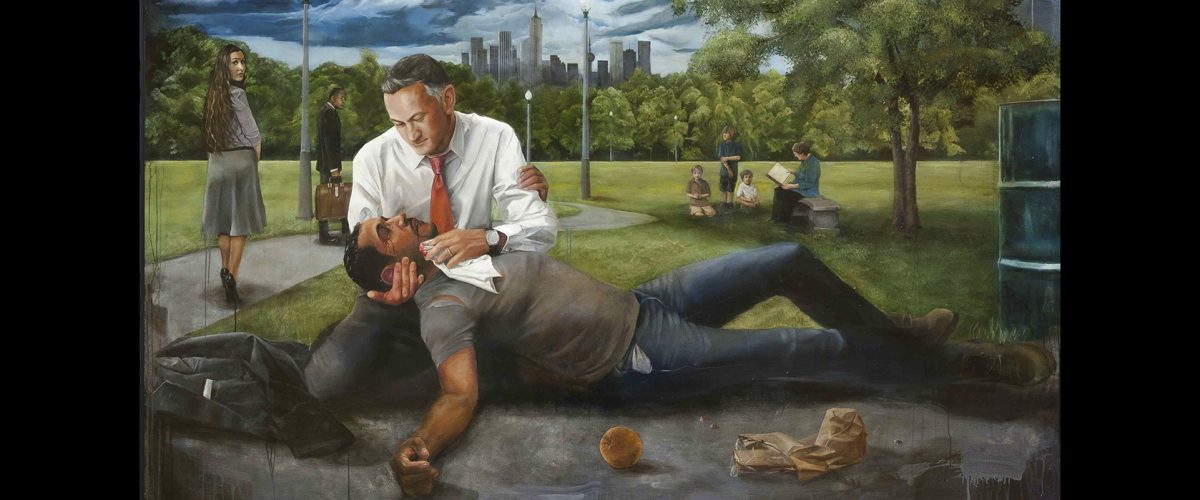

“Who is my neighbor?” The expert of the law, the one whose job it was to study Scriptures, asked Jesus this question in Luke 10. Of course, the expert probably knew the answer. He knew the original languages and pored over the Scriptures as a main factor in his job description. He asked Jesus because he wanted to trap Jesus.

Jesus did not take the bait, right? Instead, he told a story. And in telling the story, he shamed the expert.

Kate Hanch

The neighbor of the robbed and beaten man was not the pastor, whose job it was to bring the good news to the Judeans. Nor was the neighbor the Levite, that expert of the law, the one who had all the answers. The pastor and Levite ignored the man. The Samaritan was the one who saw the man and tended to his wounds.

Jesus then directed his question back to the expert: “Who do you think was a good neighbor?” The expert responded: “The one who showed mercy.”

Mercy seems in short supply these days, doesn’t it? I’m especially cognizant of that reality as the governors of Texas and Florida spent millions of dollars to fly migrants from Texas to Massachusetts without any advanced warning or directives. Who is my neighbor? Where is the mercy?

“The people of God in both testaments often are a migrant people.”

The people of God in both testaments often are a migrant people, often out of desperation and necessity. In Genesis, when famine struck, Abram and Sarai went to Egypt to escape it. They later immigrated to Canaan. Then in Exodus, the Hebrew peoples fled Egypt and became migrants in the wilderness for 40 years, living in tents and without a home to call their own. This affected their theology so much that the laws set up in Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy had provisions for immigrants. Leviticus 24:22 instructs the Hebrews not to harvest an entire field, but to leave some of the harvest for the impoverished and the immigrant.

One immigrant who benefited from these commands was Ruth. A Moabite, Ruth had married a Hebrew while living in Moab. After both she and her mother-in-law were left widowed without means of income or support, they decided to travel to Judah, where they knew the Hebrew people had provisions for immigrants. Ruth gathered barley from Boaz’s harvest — picking up the grain he had left behind according to the laws. Eventually, through Naomi’s help, Ruth and Boaz became a family, despite her status as a widowed outcast. Ruth would give birth to Obed, whom the Gospel writer in Matthew describes as being an ancestor of Jesus. We cannot forget Jesus’ early years, where his family had to flee Egypt to escape the clutches of King Herod and certain death. Jesus himself was a refugee.

In one sense, those of us who are Christians are to lessen our hold on what we deem ours, for we realize everything we have is from God. We are to realize we are living in the in-between — the here-and-not-yet of God’s reign. The writer of 1 Peter 2:11 declares that the audience should live like “immigrants” or “exiles” from the world, refusing to succumb to empire and instead opting to live toward the inbreaking of the reign of God, where “righteousness and peace will kiss each other.” What does that look like?

Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, who spoke at the Pray Vote Stand conference recently, suggested that Christian faith demands people act in a certain way when they advocate for particular issues and when they vote for particular persons. Several times he mentioned the value of “human dignity” and that human rights must be grounded in human dignity.

“Apparently, for Mohler, to show mercy is to align oneself to the people in power.”

However, he remained silent on migrants’ dignity and respect. He denigrated LGTBQ persons’ dignity. Apparently, for Mohler, to show mercy is to align oneself to the people in power. For him, to show mercy is to deny the dignity of the migrant or the outcast. This doesn’t look like righteousness or peace.

As those of us who call ourselves Christians reflect on Jesus’ teachings and the Bible, I hope we can take a hard look at ourselves in the face of our treatment of migrants. We should work for a world where righteousness and peace kiss each other, even when our pastors align with our politicians in their quest for control. I pray we may have the same answer as the expert of the law in answering Jesus’ question — showing mercy to all. Only then, may all persons know and live out their dignity.

Kate Hanch serves as associate pastor of youth and families at First St. Charles United Methodist Church in Missouri. She earned a master of divinity degree from Central Baptist Theological and a Ph.D. in theology and ethics at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary. Her first book, Storied Witness, conducts a careful reading of 19th-century Black women preachers’ narratives and their texts, both written and spoken, to make explicit their theology. She lives in O’Fallon, Mo.

Related articles:

Voting the wrong way makes Christians ‘unfaithful’ to God, Mohler says

Religious groups step up as DeSantis and Abbott make immigrants pawns for publicity

How John MacArthur loves the Bible but not his neighbor | Analysis by Rick Pidcock