After his second visit to New York in 1939, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrestled with the character of Protestant churches in America versus those in Europe in an essay titled “Protestantism without Reformation.”

Even as he introduced his argument, which plays up history, sociology and political analysis for understanding the American church, Bonhoeffer offered some words of caution about using these modes. He expressed concern about balkanizing the global church, failing to see the single, shared office of God’s church in the world, and neglecting the real value of concrete church-communities that differ from our own. And I share these concerns.

As Bonhoeffer demonstrated, however, these fields of study can help us understand important dynamics in a clearly diverse and divided church landscape. With special reference to U.S. history, he keyed on how a land that never has seen the church unified (in confession or institutional forms) thinks differently from the start about what “the church” even is.

As Bonhoeffer demonstrated, however, these fields of study can help us understand important dynamics in a clearly diverse and divided church landscape. With special reference to U.S. history, he keyed on how a land that never has seen the church unified (in confession or institutional forms) thinks differently from the start about what “the church” even is.

Origins of American church

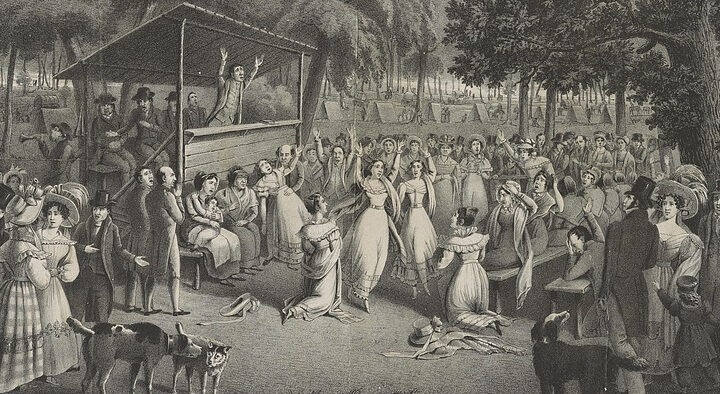

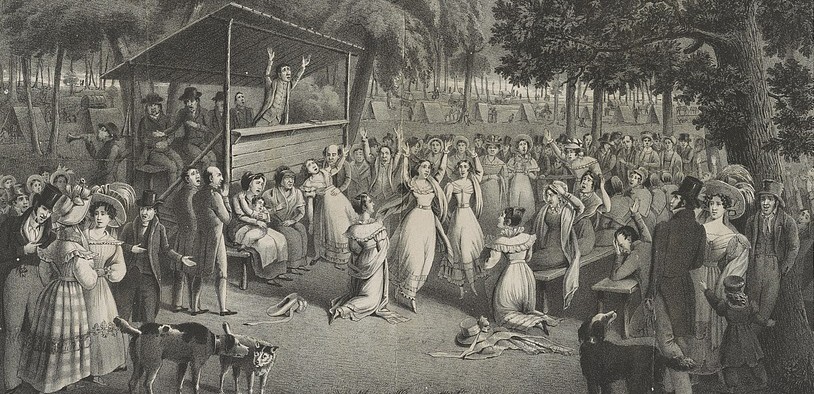

European Protestants set out to make colonies in America as they fled, voluntarily or involuntarily, from religious battles. Among the Christians who remained in Europe, the unity of the church was remembered and presupposed. So, European Protestant energy was channeled into efforts to reform the whole church, which provoked charges of heresy, real fights and other coercive attempts to bring others to “the light.”

But the origin of the American church — already diverse in confession and existing as numerous refugee communities — engendered a spirit of toleration and manifested in formal protections of religious freedom. Over time, numerous denominations formed, split and merged as free, voluntary associations of local churches with common polity and practices. And when Bonhoeffer visited America, ecumenical organizations also had been forming, on the assumption of tolerance around confessional issues even while searching for united fronts on practical matters.

In his essay, Bonhoeffer pointed up these details to explain why Christians in America might see church unity as a goal (however remote) even if few could see any reason to think there was one church-community in America — let alone feel the fight to reform the whole. Starting from within this situation, now as then, one cannot help but see variety in the U.S. church scene and puzzle at claims to represent the one, true church.

Today I will argue that the postwar evangelical movement has reshaped this picture in the U.S., generating a new way of conceiving the whole and resuscitating the will to fight for it. Specifically, I will highlight how the biblical worldview concept has enabled visible leaders of this movement to capitalize on the individualism of American culture and raise a new, ostensibly conservative standard in American public life. This move has amplified cultural divisions and damaged many Christians’ understanding of the church and its mission, so the conclusion of this essay will point toward a more promising picture of church-community for transforming the heart of these conflicts.

“The biblical worldview concept has enabled visible leaders of this movement to capitalize on the individualism of American culture and raise a new, ostensibly conservative standard in American public life.”

Neo-evangelicals’ “New Reformation”

Within nine years of Bonhoeffer’s essay (but to be clear, with no reference to it), Harold Ockenga described what he understood as “the New Reformation” unfolding in the neo-evangelical movement. Reading these two pieces back-to-back is fascinating, not least because the first pushes us to ask: What did Ockenga imagine as the target of his reformation?

Harold Ockenga preaching

Ockenga opened his essay with a stylized account of the Protestant Reformation and the historical conditions that preceded it, including the charge that the Roman Catholic Church had not allowed, and thus not benefitted from, the kind of competition that stimulates growth. The way he told the story, the whole Reformation hinged on the Bible’s liberation from human traditions into the hands of the people. A quote might help us catch the flavor of his commentary:

The Bible revealed to the people what was wrong with the church, namely, how far it had deflected from biblical teaching. Once the people began to read the Bible, they immediately recognized the distance which the church had departed from primitive Christianity in simplicity, sacrifice, and service.

In Ockenga’s view, greater “knowledge of the Bible incited the people to discussions of principles involved in Christianity.”

A liberated Bible?

Hiding here is more of the historical reality. Rhetorically, we might like to say the liberated Bible freed the people; but, in real time, literacy rates were very low, and new expositions, interpretations and emphases were circulated in two stages — pamphlets for the readers and oral accounts for the rest, between pulpit and pub.

What exactly it means for the Bible to be liberated from tradition is, in itself, an important point of conversation. Sola scriptura is lauded as one of the primary doctrines of the Reformation. On this point, Ockenga highlighted “the authority of the Bible alone uninterpreted by traditions.” And he went on to describe the Bible’s authority as “over against the authority of the church or of reason or of experience or of the inner spirit.”

While I am interested in defending this second notion, I am concerned about the way it bumps up against the first. Getting our view of Scripture right means opening ourselves to ongoing criticism because the most important meaning of Bible freedom is found in its own freedom from us. The Bible can only be for us and with us, as human beings seeking God’s face, if we honor the reality that it stands over against us.

“The Bible can only be for us and with us, as human beings seeking God’s face, if we honor the reality that it stands over against us.”

But all too often, American evangelicals have extended the authority of the Bible — as we might imagine it standing on its own, liberated from human traditions — to their translations and interpretations of that Bible. When they are our correct interpretations, we simply call them “expositions.” Hold onto this thought.

A ‘biblical’ worldview

Surveying the American social landscape in light of the primary Reformation doctrines, Ockenga was concerned with the fruits of mainline theology and social action. He saw the liberals running off course starting with contesting the Bible’s authority. They ended up following the course of modern secular folks, enthralled by the prevailing progressivism and theologizing the kingdom of God in terms borrowed from culture. The result was, in Ockenga’s view, not only disunited in effect but, more importantly, unbiblical and pernicious.

Fuller Seminary’s founding faculty: Harold John Ockenga, Wilbur M. Smith, Carl F.H. Henry, Harold Lindsell, Everett Harrison.

So, we return to ask: What did Ockenga imagine as the target of his reformation? Neither a new institutional unity (like a denomination) nor a new confession was Ockenga’s desired product — America already had too many. Rather, the New Reformation would materialize in individual Christians and some local churches taking up their intellectual starting point in the biblical worldview, embracing its supernatural elements. From there, the rest would follow much like it did in his reading of the 16th century Reformation.

Unpacking “the challenge to individual believers,” Ockenga emphasized “biblical action to fulfill God’s program.” He outlined four priorities with an intentional order: foreign mission, personal evangelism, education under a powerful expositor of the Bible, and only then social engagement in loving service and political activism. The order of the last two elements implicitly continued Ockenga’s criticism of progressive Protestants, who got the order wrong and read their Bibles through their social context and political goals.

Speaking for his own church, Ockenga assured the reader that evangelicals do not withdraw from cultural discipleship. “We … make our voice heard on all these matters of civic and legislative affairs.” And, moreover, he concluded his article with an appeal to the Reformation leaders of yore, who “would tell us that we must meet the challenge of our day for the sake of Christ … by fearlessly applying Christian truth to situations, and by sincerely carrying through to a logical conclusion these principles which we find in the Word of God.”

“Ockenga issued an invitation to join in the wish-dream of unity under a plain biblical worldview.”

To the many individuals dissatisfied with their own local church-communities, Ockenga issued an invitation to join in the wish-dream of unity under a plain biblical worldview. And he suggested they be prepared to sacrifice other loyalties and particular commitments when necessary to support this vision. The effects included weakening local ecclesial ties, engendering suspicion of real-world church-community, and underwriting libertarian, free-enterprising views of moral individuals in unvoiced multitudes.

Evangelical entrepreneurship

What neo-evangelical leaders aimed to “reform” was first the minds of individual believers. Ockenga’s vision for an evangelical Reformation cut across denominational lines to recover a unifying spirit. He decentered forms of religion and played up the feelings of common cause and core values at stake.

Focused as they were on individuals, early leaders did not anticipate strictly man-to-man operations so much as they imagined their audience to a silent majority of individuals. And even as they cast a “conservative” vision, they sought progress in the form of new associations, educational institutions, media outlets and the like. This stream of American evangelicalism always has been, as George Marsden famously observed, an entrepreneurial endeavor.

As Americans know well, entrepreneurship is inextricably linked with the free market virtue of competition. Ockenga explicitly made this link while criticizing the “monopolistic” Roman Catholic Church of the pre-Reformation era.

Churches often tailor worship to attract Millennials. That can be insulting to Millennials. (Photo/Catholic Archdiocese of Boston/Creative Commons)

When competing in a free and open market, success is measured by the literal, ongoing buy-in of everyday folks, who vote with their feet and their wallets. Thus, for decades pastors and consultants have talked about churches, particularly in densely populated areas, in terms of a marketplace. And on the supply side, evangelicals see few barriers to “church shopping,” whether moving to a new town or just growing wary of their local church’s message.

Moving in a slightly different direction, we can see how thought leaders, not least in evangelical circles, are platformed and canceled based on market dynamics more than movements of the Holy Spirit. Leaders are free and unconstrained as they attempt to gain ground or throw their weight around with appeals to an idealized worldview and its commonsense applications. And popularity and public opinion matter more than a fair amount in who gets to use such rhetoric and feel successful doing it, on whom the burdens of proof rest, and who gets to dismiss whom out of hand.

We need not read all this cynically. Competition and entrepreneurial endeavors are descriptively in the warp and woof of American evangelicalism. That fact does not mean everyone with a platform is merely self-interested or power-hungry or that no one really cares about what the Bible says. But to those who would see the biblical truth, as they have “exposited” it, shape more minds and cover more territory within their imagined audience of individuals — even to the end of a global reformation — temptations are prowling around like a roaring lion.

Market dynamics and moral outcomes

It is axiomatic that market dynamics are not always the best motivator or determiner of moral outcomes. For those who like an example, large numbers of followers, whether online or in the pews, can lend voice and influence to leaders with significant defects of character and judgment. This is one lesson from the popular “Rise and Fall of Mars Hill” podcast. But this is also how postwar American evangelicalism rolled onto the scene covered in unspoken assumptions based in worldly categories (history, sociality, politics) and not the Bible itself — even if visible leaders defended these ideas as if they were merely the biblical worldview.

For another example, we might consider the current data on how multiracial churches do (and do not) improve the overall problem unfolding in this series. This picture is coming through in books like Korie Edwards’ The Elusive Dream, numerous articles and reports on the most recent wave of the National Congregations Study. Citing these sources, Kevin Dougherty, Mark Chaves and Michael Emerson conclude that, for too many white Christians, “diversity is pursued by trying to attract people of color who will not challenge white congregants’ views and practices.” This is another feature of market dynamics even if, in many cases (although not all), problems arise contrary to the best intentions of leaders and participants.

Recalling Bonhoeffer’s comparison of the fight or flight activity of European and American Protestants, we might observe that neo-evangelicals reintroduced a “fight for the whole” mentality in the U.S. context — but in a different mode. Reconceiving U.S. history as a triumph of evangelical influence that had since waned, Ockenga framed his reformation as an attempt to recover this ideal, but non-existent, American church.

“The entrepreneurial, market-share competition for individuals’ attention and loyalty, in effect if not intention, defines the perpetual struggle for an evangelical identity.”

With no structures to fight or resist except those already deemed apostate, Ockenga and company could cast themselves as conservatives even as they created new institutions (a progressive act). And the whole project could be pursued with reference to a world-viewing population of individuals with personal knowledge of the liberated Bible and its application, standing in for “the church.”

Thus, the entrepreneurial, market-share competition for individuals’ attention and loyalty, in effect if not intention, defines the perpetual struggle for an evangelical identity. Willing participation in this struggle is, in fact, the most meaningful definition of white American evangelicalism. In this sense, it is difficult for #exvangelicals or post-evangelicals to escape this center of gravity, and other Christian traditions are often drawn into the fray as the rhetoric around biblical world-viewing (with or without the evangelical moniker) appeals to more and more individuals.

Policing the boundaries

With all the focus on an audience of free individuals, we might consider how visible leaders expect to police the boundaries of a community that literally does not exist.

The worldview concept helps its users imagine the boundaries as a particular set of ideas — some expressed in confessions, others shared for unnamed reasons and supplied by other social mechanisms. As such, individual agents can be empowered with the sense that they are involved in the bigger project from exactly where they are.

As we have seen in Ockenga’s way of reasoning, the explicit, formal claim is this: We start with the Bible, liberated from traditions of human interpretation, and then apply its teachings in the world. He does not intend for the traffic to move two ways in this process. To misplace some of Willie Jennings’s words about European Christian colonizers, Ockenga imagines “first conditioning the world rather than being conditioned by it.” All too often in evangelical circles, the folks calling the shots and issuing the invectives earnestly believe the conditioning flows one way.

As we have seen in Ockenga’s way of reasoning, the explicit, formal claim is this: We start with the Bible, liberated from traditions of human interpretation, and then apply its teachings in the world. He does not intend for the traffic to move two ways in this process. To misplace some of Willie Jennings’s words about European Christian colonizers, Ockenga imagines “first conditioning the world rather than being conditioned by it.” All too often in evangelical circles, the folks calling the shots and issuing the invectives earnestly believe the conditioning flows one way.

This is, of course, why biblical-world-viewing thought leaders feel the sting when critics go after key elements of one’s worldview as if it were merely historical, social, political. To the evangelical expositor of Scripture taking inventory of his own intentions, it simply does not feel like these categories matter much. Their efforts feel like love for biblical truth and a desire to make it plain so that more individuals can live honest, earnest lives before God. And if the audience is behind a leader, even the most obvious criticism need not be addressed in good faith.

More than that, when critical feedback arrives, the posture of world-viewing suggests strategies for dealing with dissent and resisting self-examination that are consistent with the competitive culture of a market-oriented, entrepreneurial movement. Among the most painful examples, a thought leader might paint the critic — even other insiders, with a history and experience in the same circles, acting in good faith — as actually already outside the fold because of not maintaining x, y, z idea within the worldview. “They” are actually delivering the goods of a competing worldview — as Ockenga claimed of those who had allowed reason to usurp biblical authority in their minds and hearts.

Sexual ethics under the LGBTQ heading rank among the most used watchwords today (see it in action here). Verily, just reading that sentence could give some world-viewers the “aha!” moment they need to dismiss my argument out of hand. Depending on the social circle, other key points include too much talk about racism that raises the specter of Critical Race Theory and social policies that smack of socialism.

“World-viewing contributes to the problem of confusing essential matters with the peripheral.”

Given the presupposed flow of evangelical thinking from the Bible, uninterpreted by traditions, into the details of the worldview, all these issues have predetermined outcomes. World-viewing contributes to the problem of confusing essential matters with the peripheral. After all, if the evangelical leader’s worldview is biblical down to the detail, then denying any part could mean denying the whole and, with it, the authority of the Bible itself. Any issue can become a new fundamental, if the right leader starts to feel a certain kind of pressure.

And still, the competitive, entrepreneurial energy flows in multiple directions. Worldview language and conceptuality can help anyone say (and believe) they are defending, and struggling with others over, the Bible itself. In the details, we tend to fight about our interpretations of — and even traditions of interpreting — the Bible. Sometimes the arguments bleed in strange ways, like those evangelicals who defend a “traditional” definition of marriage even when they resist traditions of biblical interpretation. But all the time, it seems, the heat rises and the polarization increases.

Individualistic idealism destroys real-world community

Claims about the worldview fit of this or that position do not actually help anyone think better or more deeply about theological issues. These claims do not encourage good-faith engagement through cooperative conversation about the heart of any matter.

Thinking one is (or at least should be) right about everything, all knowledge of good and evil, does not foster charity toward those who disagree. And such rhetoric effectively obscures from everyone why anyone actually believes this or that, which may well have biblical or theological roots that others who care about the Bible and good theology simply do not share.

Where does all this leave us on the question of the church, conceived as a unified whole, and its reform? Recalling Bonhoeffer’s view of Protestant churches in the U.S., we might conclude that evangelicals have generated a new possibility: a way for individuals to fight for and about an imaginary whole without unity in any recognizable, real-world social form.

Not a church but an audience

Over the years, the image of “evangelicalism” as an identifiable social movement has been abetted by its reality as a broad, abstract, genuinely nonexistent “community.” It is not a church but an audience — and an enthusiastic one at that. Yet individuals claimed as “evangelicals” on surveys may or may not regularly engage, let alone commit to, any local church-community of real human beings. Because evangelicalism has largely been about biblical world-viewing, in effect if not in rhetoric, too many have conceived of Christianity primarily as a set of beliefs that even lone wolves (one of Ockenga’s terms for his audience in the 1940s) can hold and defend.

“Those who belong to the wish-dream church of their minds are fundamentally untethered from the actual places and particular histories and deeper traditions that might trouble their abstract ideas.”

The born-again individual is conceived as a fundamentally free, rational agent who approaches Scripture with a sanctified imagination, enabled to read the whole plainly without traditioned interpretations. And this presupposition empowers the individual, who fixates on whether the ideas they hear in a church, through media and so on fit with all their secure, self-assured worldviews.

(Shutterstock)

Those who belong to the wish-dream church of their minds are fundamentally untethered from the actual places and particular histories and deeper traditions that might trouble their abstract ideas. They need not listen to any diverse perspectives, any feedback that might trouble their feeling that they are morally upstanding and theologically orthodox.

This untethering encourages the consumerist approach to church, such that a person can pack up, leave, and find a church that feels “more truly evangelical” any time their current church makes or supports any notion that disturbs their sense of inner unity. And it undercuts real, historical community, where local accountability is engendered and actualized (sometimes in genuine, inescapable disagreements).

Unaccountable individualism

Together, these moves further ensconce the unaccountable individualism that is so characteristic of certain sectors of American public life. The advent of social media in a world, in a church, without the communal and conversational virtues to make good use of it, has only exacerbated these trends.

On this point, I think of Bonhoeffer’s argument around church-community in his classic Life Together. In the first chapter, he taps into the fundamental nature of the church, saying, “Christian community is not an ideal we have to realize, but rather a reality created by God in Christ in which we may participate.”

For one thing, this means we cannot approach genuine church-community with abstract, idealistic notions — including everything everyone must agree with — that we expect to be realized among the people with whom we are willing to share a table (whether God’s table or our family’s). “Those who love their dream of Christian community more than the Christian community itself,” Bonhoeffer tells us, “become destroyers of that Christian community, even though their personal intentions may be ever so honest, earnest and sacrificial.”

Real-world church-community as the alternative

As the evangelical brand continues to unravel around us, and as more critics register its massive failure of discipleship, more of the audience is seeing where certain ideals — that actually have historical, sociological and political tinges — have supplanted the reality.

The rhetorical fixation on the biblical worldview has inaccurately represented and sinfully mishandled everyone it has helped imagine, judge and police, and all the while it also has provided exhilarating motivation for the powerful world-viewer to press on with their agenda as if it were God’s very will.

Too often, this has meant imagining other persons in abstract terms as some number of individuals who must be, frankly, wrong and just need to get with the biblical program. But too much focus has left too little space and energy to empathize with and engage the complex human beings around us in local spaces in good faith.

Unbeknownst to us, as we objectify and judge others (sometimes in online spaces) within our secure worldview categories, we inflict wounds upon our own souls. Instead of love, we nurture the desire to control others. Instead of seeking more justice in real community, we fuel competition over the vision and defer charitable action.

I do not imagine the worldview concept can be rehabilitated for use in a more humble, creaturely communion, nor do I underestimate the challenges of seeing or approaching a new way of inhabiting the world from the broken conceptual moment in which we currently live and move and have our being.

Unity is not within our control

However we may interpret the situation at hand, Bonhoeffer is ready with the words we do not want to hear: “Is not what has been given us enough: other believers who will go on living with us through sin and need under the blessing of God’s grace? … Even when sin and misunderstanding burden the common life, is not the one who sins still a person with whom I too stand under the word of Christ?”

Lest we interpret this notion already as a justification for how we prefer to identify sin — the most pressing issues, in the lives of imagined others, seen from within our secure worldviews — let us remember that, in Jesus’ own words, the kingdom is already nearer to those who experience oppression in this world (to the tune of Matthew 25). And because they represent a different constellation of realities, other persons can alert us to our sin and self-deception, offer alternative interpretations of the situation at hand, and make us responsible agents in our actual places.

“Unity is the church’s origin, and its realization is no way, shape or form within our control.”

On the point of church-community, we must keep before us its deepest truths: God is the author of both our community and our faith, and God’s work always, already underlies the reality of the many churches. So, unity is the church’s origin, and its realization is no way, shape or form within our control. We neither get to preselect nor police (in the ways we tend to think) who partakes in community with us. And, troubling our false worldview security, God appears to us in others to share words we still need to hear — words we might not otherwise select for, and even still might struggle to hear and grapple with, ourselves.

We must learn to acknowledge how God goes ahead of us, creating not only the possibility of community but the very church-community itself. Christians are called out of the world and drawn into this people as the forgiven, who thankfully receive with open hands and without demands. This frees us to hold our truth differently within our local communities and, by extension, in the conversations that cross those communities — including in online spaces. When all are liberated to converse in good faith, when even dissenters can hold their ideas and their reasons out to others with an open hand, churches (where two or more are gathered) can become training grounds for unhinging the world’s polarizing, competitive interaction.

To believe this, to live into this reality, will require nothing short of repentance — turning away from world-viewing into a true alternative to all this strife. More on this theme will follow in my final article for this series.

This is the fifth in a series of articles introducing the hypothesis of the author’s new book, Worldview Theory, Whiteness, and the Future of Evangelical Faith.

Jacob Alan Cook

Jacob Alan Cook is a postdoctoral fellow at Wake Forest University School of Divinity. He is the author of Worldview Theory, Whiteness, and the Future of Evangelical Faith as well as chapters on Christian identity, peacemaking and ecological theology. He earned a Ph.D. from Fuller Theological Seminary.

Related articles in this series:

What if your ‘Christian worldview’ is based upon some sinful ideas?

A short history of the roots of colonialism, racism and whiteness in ‘Christian worldview’

Putting the white in witness since the 1940s

Why your worldview might be both more and less than biblical