The state of the conversation around race in many corners of America, including too many churches, is a mess. And before we get too far down the road, I want to register my hesitation about trying to abridge what I argue with greater care and detail in my book. Wading into the borderlands of critical race studies is perilous, especially in a social climate where even the mention of terms such as “whiteness” is a nonstarter.

My hope is to join or open a genuine, searching conversation, not shut down the very possibility. But I have seen enough to know how tough that needle is to thread — not least when one must start with an article title provocative enough to grab attention.

I am seeking to understand the heart of American churches and their people. This work has not made me the slightest bit cynical. Instead, it has driven me to learn more about faith formation and moral psychology — to wrestle with what motivates our thinking and behavior. This includes the complexity of our soul wiring, the role of intentions, the pressures of our social networks and other vital details.

I believe deeply in the ongoing effects of sin in this world, and I believe God does not leave us without hope. But better world-viewing is not that hope. As I will argue more directly later in this series, world-viewing is a refined repetition of the first humans’ attempt to seize the knowledge of good and evil as a secure foundation for life in this world. Their intentions could well have been pious — as in, this way we can know and do God’s will. But the result was a broken relationship with their living Maker, who is our only true source of security.

While our intentions toward one another today may be pious — and I hope they are! — our way of engaging one another bears the marks of humankind’s relational brokenness. This assessment certainly is accurate when we are more interested in how others square with our worldview than in who they are before God in the world itself.

So, I will chart some of the racial contours of worldview theory as it emerged on the landscape of the modern West. We will check in on the project at critical intervals, pulling out vignettes of the early days of colonialism and modern worldview theory. This article will be history-centered, while the next installment will make contemporary connections between world-viewing and whiteness.

World-viewing as a “white” impulse

The concept of worldview and the modern idea of Western “civilization” are bound together with the history of white Europeans colonizing foreign lands. I suspect we all know key bits of this story, in which a special variety of “civility” was used to end or otherwise order the lives of human beings who were objectified in terms of their perceived barbarity and general heathenism.

In those days, worldview emerged as something like an impulse within early European globetrotters, who encountered and categorized different “others” around the world. As they classified all the persons and peoples they met out there, something happened within the colonizers too. In the experience of profound cultural difference, these globetrotters assumed something like a civilized Christian worldview was a part of themselves, bound not only to their souls but to their bodies and no longer confined to their homelands.

In the experience of profound cultural difference, these globetrotters assumed something like a civilized Christian worldview was a part of themselves, bound not only to their souls but to their bodies and no longer confined to their homelands.

Previously, white Europeans may have assumed the power and promise of Christian civilization to have a world-transforming trajectory. But in regular, living contact with dark-skinned people from Africa, they interpreted their sense of cultural superiority through the visible marker of skin color. This is how they knew a person’s identity and potential in the world as they viewed it.

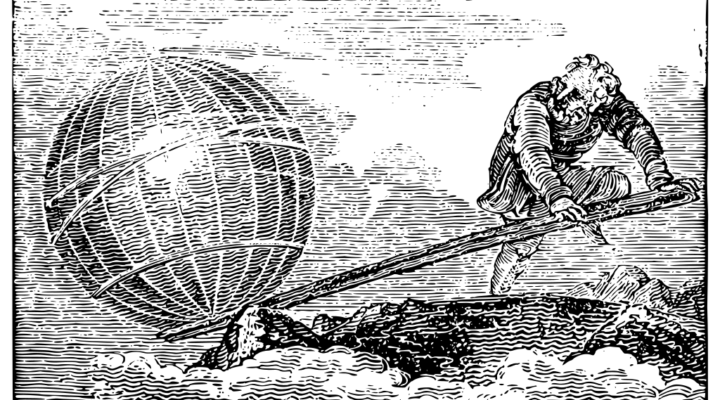

As their understanding of the world and its peoples expanded, the position of the white world-shaper within the global picture of human existence became their standard for judging everything and everyone. But these folks were thinking about the world through their worldview, not thinking critically about their worldview itself. The evident problems with this perspective — the hubris of thinking one can imagine the whole world, including their place within it — did not appear to their conscious minds as a problem.

Here we might begin to grasp how worldview theory, as it relates to the history of whiteness, is at least partly a matter of scale. Before the “scale of whiteness” became a hierarchy of races traced along the gradient of racial purity, the concept of scale was about the size of a person’s thoughts. Powerful white folks thought they could locate everything and everybody on their blueprint for a remade world—and they felt they had God’s approval to do it, often taking missionaries in tow. So, what we call “whiteness” materialized subtly, as theologian Willie Jennings has described, “not simply as a marker of the European but as the rarely spoken but always understood organizing conceptual frame.”

White philosophers get into world-viewing

As modern philosophy unfolded in the post-Reformation world, any semblance of a broadly shared framework held together by a Christian empire, however superficial it may have been, washed away. In the vacuum, personal identity and individual freedom made their way toward the center of the ring as matters of serious deliberation, especially for the well-educated.

The exalted modern philosopher Immanuel Kant, active in the 1700s, was the first known to employ the term worldview — Weltanschauung, in his native German, although you may have heard that word in English-speaking circles too. While it is tough to say exactly what Kant meant with the term, since he only used it once, I suspect he was talking about the relatively simple, intuitive perception that the world in its many parts is yet one system. This being the case, we can assume a kind of logic runs through the world that encourages us to explore and discover.

That is reasonable enough. But it is worth lingering to ask how Kant’s eminently rational way of picturing the world might still have reflected, rather than set, the tone of his culture. With the contours of the new world, its colonies and peoples coming into view, many thinkers were incorporating relevant details in their theories.

And it just so happened that, in Kant’s view, only bourgeois European males could hope to attain the natural, universal end of humankind — self-perfection while exercising human freedom. He intuitively located reason and the meaning of human life itself within a pseudo-scientific racial hierarchy fit for Europe’s colonial enterprise.

Kant also was critical of colonialism, especially in his later writings. But close readers note the lingering question of whether it is better for the civilized to actively develop other corners of the world and their peoples toward realizing humankind’s potential.

In the next generation of philosophers, others in the idealist school developed the worldview concept more explicitly and layered in their own takes on nation and race. For one, F.W.J. von Schelling developed the worldview concept as a more conscious, more active way of engaging the world. At the same time, he imagined white Europeans had escaped the historical process by which “the other part” of humankind “degraded into races.” Or more than escape, Schelling thought this people may well have overcome that process, “appoint(ing) itself to higher spirituality.”

Notice here the germ of what the pioneering sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois named the “attempt to transmute a physical accident into a moral deed — to draw unreal distinctions among human souls.” So much of worldview theory amounts to virtue by association.

One last philosopher before the theological turn

Foremost among worldview scholars in the generation after Kant was G.W.F. Hegel, active into the early 1800s. To start, he described history as a system in which reason itself was making progress toward its fullest form — namely, nation-states consciously oriented toward freedom. And Hegel interpreted various human civilizations in history as handing off the lead in this progress, culminating in the glory days of Protestant Europe. Once a Lutheran seminarian, Hegel saw his philosophical work as seeing the Reformation through to its end.

From the vantage of no mere world-viewer but a critical agent standing above all worldviews, Hegel thought he could see the whole world System reaching its goal in the society around him. His view of non-Western civilizations is well-known. He believed dark-skinned Africans’ souls remained undeveloped, about as far as humanly possible from the rational worldview to which white Europeans had ascended collectively.

Before moving on, I should mention that Du Bois vigorously objected to Hegel’s claims about African culture. And he did so from within Hegel’s view of history, naming the good that could come from recognizing a distinctive African spirit and attempting to synthesize its moral goodness into America’s material progress. We will pick up parts of Du Bois’ analysis and response later in this series.

To sum up the story thus far, worldview theory emerged as something of the crowning achievement — the capstone, if you will — of the early modern philosophical agenda. And it emerged in the same period that folks were stealing lands and persons and developing pseudo-scientific theories to explain differences among those who looked and lived in different ways. Worldview theory grew out of the seemingly obvious racial logic of the colonial enterprise, even as it justified the sense of supremacy enjoyed by white Europeans spreading their seed upon the face of the earth.

Even this much texture is missing from now-standard treatments of the worldview concept in evangelical circles. For example, in his history and praise of the concept, philosopher David Naugle plots these same points — Kant, von Schelling, Hegel, and even Abraham Kuyper, below. But with the addition of each thinker, he makes no mention of their troubling colonial racial imaginations, which took in the whole world and all its peoples and imposed a new order upon them. Who felt the need to see, judge and order the entire world in the first place?

World-view theory gets its theological legs

Over time, modern science and philosophy gained ground in developing an increasingly comprehensive worldview. And many theologically minded folks grew concerned that the space for God within this view was diminishing in the minds of too many. Even the faithful guided their everyday lives by prevailing cultural winds more than careful, faith-oriented reflection.

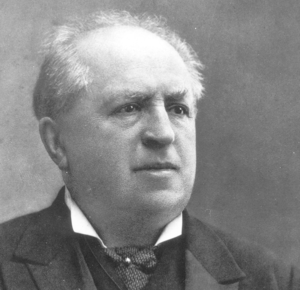

As he surveyed European civilization in the late 1800s, Abraham Kuyper saw the need for Protestant Christians to spell out their worldview for the first time to inspire a unified front in combatting the challenges of their day. Under Roman Catholic influence, the Western world had made progress toward the ideal. While the spirit of the Reformation promised the completion of that project, it splintered and stalled before consciously developing its distinctive form for thought. Now, folks filling out a godless, scientific worldview were outpacing Protestants.

So, the worldview project first appeared on Kuyper’s radar, not as a translation of some biblical notion or an inherited Christian tradition, but because it glimmered in a particular historical moment as a response to what was going on in the world. In fact, he got swept up in Hegel’s way of understanding history in terms of successive worldviews. And Kuyper believed that, had the fall (Genesis 3) not occurred, Hegel’s way of understanding how human knowledge and consciousness develop would be fundamentally true to form.

However, in the world we have, Kuyper argued, sin cleaved the collective mind of humankind into two parts—the born-again and the rest. As he sought to re-theologize Hegel’s ideas, Kuyper located the world-viewing impulse in the very image of God. Having made the world in an orderly fashion, God created humankind within that world as the creature that could become consciously aware of how everything fit together.

Human beings could reflect back to God a full-orbed image of what God revealed in creation precisely by pursuing such vast knowledge. This original revelation included the patterns for our lives together, which would become more evident over time according to divinely set patterns. Ultimately, Kuyper shared Hegel’s vision of nations as the material substance of God’s will unfolding upon the face of the earth.

Reflecting the Christian nationalism of the period, Kuyper defended Calvinism as the only theological stream flowing from the Reformation that “has established not only churches but also States, has set its stamp upon social and public life, and has thus, in the full sense of the word, created for the whole life of man a world of thought entirely its own.”

Troubling applications of a biblical worldview

A good many contemporary thinkers find nothing objectionable in this much of Kuyper’s theory. But we must also ask of him what we asked of the philosophers: As he developed his worldview, in theory and in detail as the very revelation of God, might he have reflected the tone of his culture?

At the 1898 Stone Lectures at Princeton Theological Seminary, Kuyper tied American and Dutch progress to the Calvinist spirit — as the basis for a Calvinist worldview. Looking across the global scene, he set his worldview in contrast to the “far lower form of existence” observed among Africans while lampooning China, Mexico and Peru — referring to ancient civilizations like the Incas — and “the Slavic races.” And visiting the same America in which Du Bois was beginning to name the color-line, Kuyper saw no hope for lasting racial reconciliation.

Kuyper boasted in the commingling of once-tribal blood among white Europeans wherever Calvinism had flourished — perhaps something of a surprise to modern readers. Elsewhere, he made a big show of how Dutch colonizers had studiously avoided “liaisons with Negro women, which have always been the disgrace and scourge of colonizing nations.” In both places, he was making the connection between the quality of bloodlines and the quality of thought lines.

Kuyper saw no end in sight to racial hierarchies, even grounding them in Scripture as well — specifically, the Genesis 9 account of the post-flood curse of Ham.

In the course of his work, which flowed in and around the variety of colonialism that continued into his time, Kuyper vindicated the basic project as part of God’s will for filling and subduing the earth. He defended Dutch colonial endeavors in South Africa as a necessary fulfillment of God’s commission in Genesis 1 to fill the earth and subdue it. “We must never, as long as we value God’s Word, oppose colonization,” Kuyper argued. “Is it not simply human folly to remain so piled up in a few small places on this planet?”

And Kuyper saw no end in sight to racial hierarchies, even grounding them in Scripture as well — specifically, the Genesis 9 account of the post-flood curse of Ham. Worse yet, though, while he charted these racial distinctions with worldview-ish flare, he also articulated a view of God’s election that associated the preferred statuses with God’s utter determination of history down to the details of “differentiation” and “inequality” of individuals’ lives.

For those who are less familiar with Kuyper as a figure, it is worth mentioning he was a politician in addition to being a theologian and churchman. Elected to public office for the first time in 1874, he served his country with almost 15 nonconsecutive years in the House, four years as prime minister and seven years in the Senate. Kuyper entered politics as a young man who sensed convictions, and the worldview within which they come to be articulated, are of deepest consequence.

The problems run down to the foundation

Worldview theory appeared in the Western imagination as a philosophical form — not a theological one. But pressures from without made it seem good and right to folks like Kuyper to seize this tool and bend it toward God. The world-viewing impulse pushed him, from a Christian perspective within the world, to rise above the fray to see and to account for the whole world of activity — including analysis from the heights above all peoples.

Locating this impulse within the very image of God, Kuyper justified this kind of work as the universal goal of humankind — now confined to the born-again part that is positioned to understand and enact the original-creational moral features of the world.

While Kuyper tried to articulate what he thought were the general, abstract details of the moral universe, he struggled hard — as all natural-theological thinkers do — to sort out the details of what is universal or essential to human nature by design and what is a historical accident. This is a key challenge for human minds trying to discern too many moral details from observations about a created world impacted by the fall.

As a posture, world-viewing is not merely about walking through God’s world and beholding its wondrous architecture. It is the basis for remaking the world after whatever a person or group holds in their mind(s) as its ideal structures.

The trouble with world-viewing is, in part if not the whole, located in assumptions around just what human beings can know and how. From its inception, worldview theory has been about seeing and understanding the whole world, at least in general terms.

As a posture, world-viewing is not merely about walking through God’s world and beholding its wondrous architecture. It is the basis for remaking the world after whatever a person or group holds in their mind(s) as its ideal structures. And I hope the vignettes above convey some of what it means that this posture became all the more prominent amid the troubling dynamics of colonialism and race — both as a byproduct and a defense of this activity.

Who needs to see and order the whole world, whether in general or down to the details?

Let’s push pause

At bottom, I am arguing that world-viewing, as a way of inhabiting the world today, is indisputably bound up in the all-seeing, all-ordering whiteness that has generated the modern world. The idea didn’t just happen to come up in the same period as colonial expansion — it helped frame what was happening and justified the progress of Christian civilization.

All that said, the problems at the heart of worldview thinking are not new to modernity; they did not emerge for the first time alongside modern racial frameworks. Rather, whiteness is one prevailing head of an enduring, hydra-like problem generated atop humankind’s deep insecurity following the first humans’ alienation from the garden and its God.

By the end of this series, I will argue what I can only claim here, that world-viewing does not flow from the reversal of our cognitive rebellion but rather is the cognitive structure of that very rebellion. Once we have abandoned our limit as creatures within the created world, the worldview concept offers a vehicle for principalities and powers — racism, economic exploitation, militarism, and the like — to generate hostility across time and space. These powers include whiteness, but this phenomenon is neither delimited nor determined by skin color.

In the next installment, I will start bridging this history into the new evangelical movement in the United States. And with all these pieces in view, I will flag some places this history resonates with white evangelical world-viewing today, including how witness picks up its silent letters as a function of whiteness.

This is the second in a series of articles introducing the hypothesis of the author’s new book, Worldview Theory, Whiteness, and the Future of Evangelical Faith.

Jacob Alan Cook is a postdoctoral fellow at Wake Forest University School of Divinity. He is the author of Worldview Theory, Whiteness, and the Future of Evangelical Faith as well as chapters on Christian identity, peacemaking and ecological theology. He earned a Ph.D. from Fuller Theological Seminary.

Jacob Alan Cook is a postdoctoral fellow at Wake Forest University School of Divinity. He is the author of Worldview Theory, Whiteness, and the Future of Evangelical Faith as well as chapters on Christian identity, peacemaking and ecological theology. He earned a Ph.D. from Fuller Theological Seminary.

Related articles:

What if your ‘Christian worldview’ is based upon some sinful ideas? / Analysis, Jacob Alan Cook

Research finds Christians hold dizzying array of historically non-Christian beliefs

The deconstruction of American evangelicalism / Opinion, David Gushee

California and the making of American evangelicalism | Analysis by Andrew Gardner