The Christmas Day sermon by the archbishop of Canterbury is the centerpiece of the Church of England’s seasonal celebrations. However, with the resignation of Archbishop Justin Welby, Anglicans will have to make do with a homily from the bishop of York before they tuck into the Christmas turkey.

Welby resigned in November after a report was released detailing physical, sexual and emotional abuse of at least 130 boys and young men by lay leader John Smyth at a Christian boarding school and at religious camps in the UK and Africa. The decades-long cover up of this abuse by the Anglican Church and the archbishop’s failure to act prompted survivors, members of the General Synod, fellow clergy and the public to call for his resignation.

While archbishops have been beheaded in the 1,400-year history of the church, never has the denomination’s most prominent leader resigned over an abuse scandal.

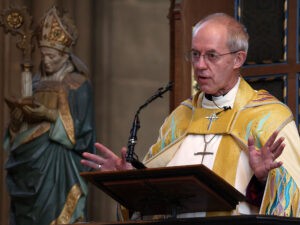

Justin Welby, archbishop of Canterbury delivers his Easter Sermon at Canterbury Cathedral on April 17, 2022, in Canterbury, England. (Photo by Hollie Adams/Getty Images)

The mainstream media’s coverage of Smyth and the archbishop’s resignation has sparked speculation about who might succeed Welby as the 106th archbishop of Canterbury as well as renewed scrutiny of the selection process.

Those unfamiliar with the Church of England’s hierarchy may remember the archbishop as the clerical figure who presided over the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II and coronation of King Charles III. In addition to such ceremonial duties, the archbishop of Canterbury holds a seat in the British Parliament’s House of Lords, oversees the Anglican churches in 160 countries, and manages the administration of the English and Welsh branches of the church in the UK.

What the new leader will face

Welby’s successor inherits not only an institution reeling from scandal, but one rife with distrust and division. In 2022, Sir David Lidington, a member of the Church of England and the former lord chancellor under Theresa May, was tasked with improving governance in the church. Asked about his investigation into the Church of England, he said: “The lack of trust and the degree of acrimony was something that really did shock me, and I was used to all of this in politics! I hadn’t expected to find it in the same way in church.”

Theologian John Milbank believes “the question of parishes” is the “biggest issue” that will face the incoming archbishop. Prior to his call to ministry, Welby worked 11 years as an oil executive, and he brought that corporate mindset with him. He centralized control of the Church of England and expanded its bureaucracy. There is now one administrator for every three and a half parish priests. In a quest to “modernize” the church, Welby’s administration closed or combined dwindling parishes and funneled millions toward experimental churches and “resource hubs.”

Reacting to cuts in parish staffing and budgets, some clergy and laity have organized the “Save the Parish” movement to protest the devaluing of the local church. With regard to the next archbishop of Canterbury, Helen King, a member of the General Synod, says, “There is a strong feeling within the church that we don’t want another manager type.” Instead, she believes members are looking for a successor who has spent more time in parish ministry and has “more pastoral feel than a managerial feel.”

Appealing to three sectors

Rowan Williams, the 104th archbishop of Canterbury, described the Church of England as having a heritage comprised of “strict evangelical Protestantism,” “Roman Catholicism” and “religious liberalism.” Like beneficiaries at the reading of a will, the Anglo-Catholic and evangelical branches of the Church of England are squabbling over who will inherit the church. (Liberalism may be poised for a revival in the future but is not, at present, a contender.) During archbishop Welby’s tenure, evangelicalism has risen to the fore.

Welby himself was a longtime member at Holy Trinity Brompton, a charismatic evangelical multi-site megachurch in London, where he was later accepted for ordination. With its £10 million budget and staff of 45 clergy members and ordinands, HTB has been the archbishop’s strategic and financial fulcrum in his attempt to reorient the Church of England to be more outward looking and evangelistic.

HTB receives millions in funding for church planting from the Church of England’s Strategic Mission and Ministry Investment and trains a fourth of all the priests in the Church of England at its seminary, St. Mellitus College.

The dominance of evangelicalism within the Church of England has impacted the pool of potential bishops vying to be the next archbishop. A majority have the same evangelical theology as Welby. From the 20th century onward, the tradition has been to alternate between an evangelical and an Anglo-Catholic archbishop of Canterbury. Should the church continue with this pattern, the 106th archbishop would be an Anglo-Catholic. However, the Crown Nominations Commission, which selects the next archbishop, may have a difficult time finding many Anglo-Catholics to choose from.

Influence of LGBTQ debate and Global South

The Church of England’s deliberations over supporting the rights of LGBTQ parishioners and clergy have created further division within the church. Conservatives, including HTB and some churches in its network, are threatening to leave over the General Synod’s endorsement of stand-alone services for blessing same-sex unions, and the House of Bishops consideration of same-sex civil marriages for clergy.

Twelve of the 42 archbishops representing Anglican communion provinces have broken with the archbishop of Canterbury over the same-sex marriage issue. Doctrinally, marriage is defined as the union between a man and a woman, even though same-sex marriage itself is legal in England. Traditionalists fear the church is violating its own stated beliefs. Progressive clergy, however, want to provide marriage blessings to LGBTQ people who currently feel like second-class members within the Church of England.

The blessing of same-sex marriages in the United Kingdom also has caused division within the broader Anglican Communion.

The blessing of same-sex marriages in the United Kingdom also has caused division within the broader Anglican Communion. Of its 85 million members, 75% live in the Global South, where churches in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia are more conservative on social issues. Global primates have accused the Church of England of straying from the “Anglican way” and announced a state of “broken communion” with the church.

To solidify the church’s international legitimacy, in 2023 the General Synod increased the number of representatives from the global Anglican Communion on the Crown Nominations Commission. The 106th archbishop will be the first chosen with greater input from these more conservative bishops whose views are opposite those of most UK citizens.

While Anglican churches in sub-Saharan Africa are growing, weekly attendance in the Church of England has fallen during Welby’s tenure from a million to 685,000. This decline is part of a larger trend in the UK. In 1983, 40% of UK residents identified as Anglican, a figure that had dropped to 12% in 2018. Some members of the Church of England think the archbishop’s time would be better spent shoring up the church at home. “He should prioritize the needs of the Church of England. The clue is in the name,” wrote Giles Fraser, vicar of St. Anne’s, Kew.

Could it be a woman?

Conservative bishops in the global Anglican Communion are also less likely to support the election of a woman as the next archbishop of Canterbury. In 2014, the General Synod voted to approve the consecration of female bishops over the objections of traditionalists. Ten years later, there are still clergy and members within the Church of England who oppose women serving as bishops and think it’s “too soon” for a female archbishop.

However, there are currently 25 female bishops in the UK, and almost a third of the Church of England’s full-time clergy are women. More women than men are training for the priesthood, so the “too soon” argument is rather difficult to justify.

Women also are viewed as more trustworthy when it comes to matters of keeping children and vulnerable populations safe, which is especially important in the present context. Welby’s attitude toward the survivors of Smyth’s abuse was deemed insensitive by many inside and outside the church.

The evangelical camps where the abuse occurred preached muscular Christianity, sexism, and practiced a theology imbued with violence. Installing a woman as archbishop would be a rebuttal to the hyper-masculine culture that permeates some corners of conservative evangelicalism. It’s also become commonplace for institutions beset by scandal to appoint women to repair their reputations. Whether those women are granted the authority to clean up problematic culture and make the necessary changes is another matter.

The process

The Crown Nominations Commission has been responsible for choosing the next archbishop since 1976. Chaired by a layperson who is appointed by the prime minister, the 17 member CNC consists of the archbishop of York, another senior bishop, six members of the General Synod (three lay and three clerical), three representatives of the diocese of Canterbury and five members from the global Anglican Communion. Once the CNC has decided on a candidate, they will submit that person’s name first to Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who will pass the name on to King Charles III. As the head of the Church of England, the king will officially appoint the archbishop. Finally, the dean and chapter of Canterbury Cathedral hold a vote to affirm the king’s selection. The new archbishop is then enthroned in the chair of St Augustine at a public ceremony in Canterbury Cathedral. The entire process is projected to take six to eight months and must be completed before Epiphany 2026.

While bookmakers aren’t taking bets yet on who will be the next archbishop of Canterbury, they have narrowed down the list of possible names. Theoretically the candidate could be any member of a church in the Anglican communion; but realistically he or she will be one of the 107 bishops in the Church of England. Because the archbishop of Canterbury must retire at 70, the commission is unlikely to choose someone much past the age of 60. Thus, a few names already have begun to circulate.

Some likely candidates

One popular choice is Rachel Treweek, the bishop of Gloucester, who was the first woman appointed a diocesan (senior) bishop in 2015 and was the first female bishop to sit in the House of Lords. She made waves in the church for saying the Church of England should stop using male pronouns when speaking of God, and she has criticized the church for its lack of diversity.

Two other female bishops also have a number of advocates.

Guli Francis-Dehqani, the bishop of Chelmsford, has a compelling life story that is drawing attention and admiration. Her father, a Muslim convert to Christianity, was the bishop of Iran before he and his family were forced to flee during the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Francis-Dehqani spoke in the House of Lords about her brother’s murder by revolutionaries seeking to kill her father. Her personal experience might be especially beneficial for navigating the UK’s deep political divide concerning how to address the refugee crisis in Europe.

“The idea of having a bishop who understands racism and immigration is very important,” said Helen King. “But she’s also a superb bishop, and she tends not to follow the party line. She’s quite outspoken, which I think is a good thing.”

Her reputation as a pastoral bishop, more concerned with parish ministry than bureaucracy, is appealing to those who found Welby’s management overly corporate.

Another female bishop, the bishop of Dover, Rose Hudson-Wilkin, is the first Black woman to be appointed a bishop in the Church of England. Her selection as archbishop would be a significant step toward calming and healing racial tensions that resurfaced during the Black Lives Matter protests in England. Known for speaking out on institutional racism, Hudson-Wilkin has drawn criticism from conservatives. She also is a suffragan (junior) bishop, and at age 63 might be considered too old to be made archbishop.

Among the men under consideration is Martyn Snow, the bishop of Leicester, who was born in Indonesia to missionary parents and worked as a chaplain in West Africa. Snow is interested in issues surrounding poverty and has spoken out in support of racial justice.

He has been the lead bishop in the Church of England’s “Living in Love and Faith” program, designed to promote empathy and understanding for LGBTQ church members. That inspired the current move to bless same-sex unions, and some see Snow’s ability to hold the church together during that process as proof he could do the same as archbishop.

Graham Usher, the bishop of Norwich, also is on the short list. Usher grew up in Ghana and has been the key bishop on environmental issues. With 75% of adults in Britian worried about the environment, and the same percentage making changes in their daily lives to do something about climate change, the issue could be a unifying one for the country.

His focus on the environment might also appeal to the younger generations currently leaving the church. King Charles III is a committed environmentalist and friendly with Usher. If the committee is looking for an Anglo-Catholic to follow Welby, Usher would fit the bill.

“We’ve gone from Rowan Williams, clearly highly academic, a thoughtful, pastoral, priestly sort of leader, to Justin, who has more of a background in the world, a more evangelical background,” said King. “Does that mean we flip back again? Or can you find someone who is somewhere in between?”

In the past, the church has chosen archbishops who are the opposite of their predecessors. Fraser, who predicted Welby’s appointment, says, “Francis-Dehqani would absolutely fit that profile of being someone completely different, and actually might excite people.”

Whoever delivers next year’s Christmas Day sermon will face many challenges uniting a divided church.

Related articles:

Archbishop of Canterbury waffles, bringing more pain for survivors | Opinion by Christa Brown

Archbishop of Canterbury sets an example of accountability | Analysis by Christa Brown